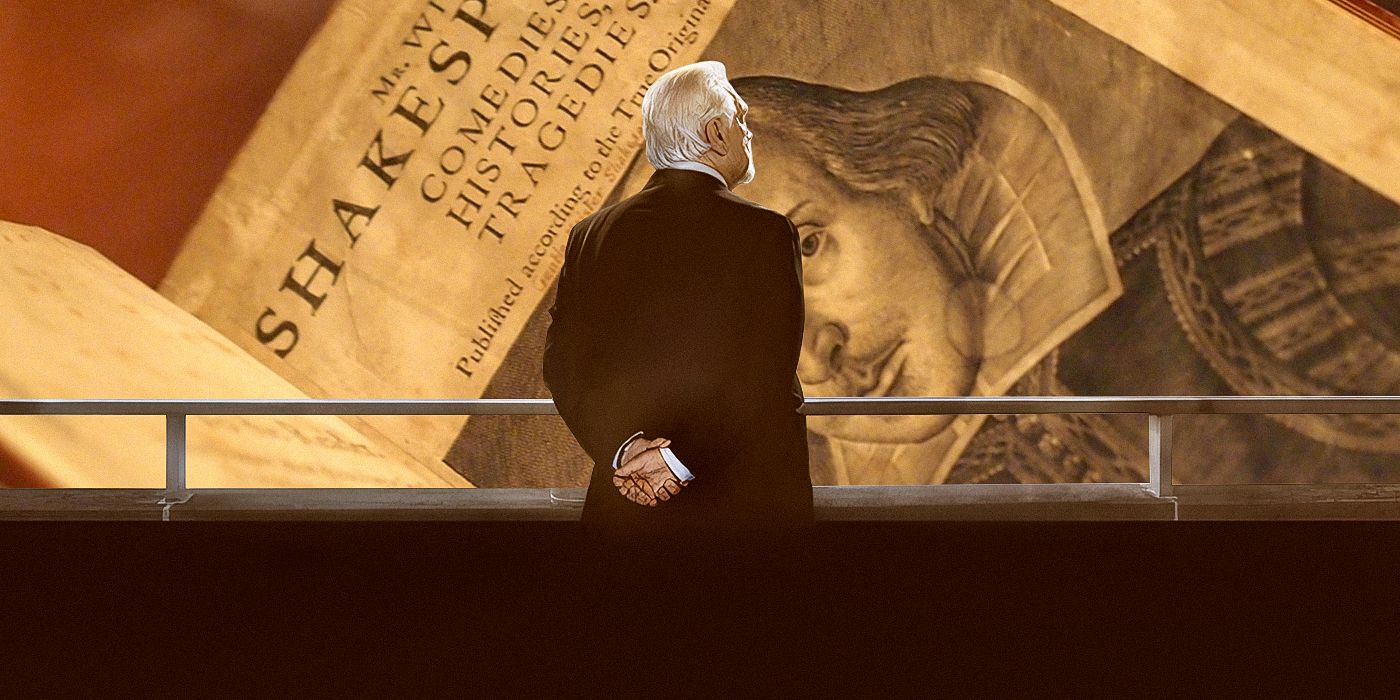

Editor's note: The below contains spoilers for the series finale of Succession.“We have to go into battle with a king.” In the series finale of Succession, Kendall Roy (Jeremy Strong) makes this argument to his dubious siblings in an effort to rally their support for his claim to the throne — er, CEO’s ergonomic office chair. It’s no “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more,” William Shakespeare’s famous exhortation from Henry V. But it does reinforce the series-long preoccupation with monarchic dynasties, lineage, and fealty to authority — concerns that live at the core of the Shakespearean tragedies of power-hungry would-be rulers that Succession has always drawn from and drawn comparisons to. Shakespeare and Succession both keenly and ruthlessly examine the corrosive effects of power and its pursuit and the ways in which unfettered ambition sustains until it annihilates.

'King Lear's Influence on 'Succession'

These comparisons to Shakespeare have abounded throughout the series’ run, and they’ve been used to try and divine who might “win” (if climbing to the highest bough of the poisoned and rotting tree that is Waystar Royco can be called “winning”). For much of Succession's run, it's been compared to King Lear, the story of a monarch who plans to retire and split his kingdom between his three children, setting off a power struggle that ends in personal and political destruction. Each sibling must perform demonstrations of love and devotion to him; when his favored daughter Cordelia refuses to play the game, her elder two sisters split the kingdom between them and immediately double-cross each other, their husbands, and Lear himself to win the other’s share. In the end, Lear and all his children are dead, and the kingdom is left in shambles. The comparisons are obvious: Logan (Brian Cox), the king, has three children competing to earn their father’s love and, by extension, his kingdom once he abdicates it. They backstab each other, they rebel against him, and they ultimately destroy themselves and each other before any of them can win.

Tom and Shiv Are Like the Macbeths

But the show has never been only King Lear. Once Logan died at the beginning of this season — something that doesn’t happen to his Shakespearean counterpart until the final moments of the play — the show’s other Shakespearean influences stepped into the spotlight. One of them was outright named in the finale: Macbeth, a story of a husband and wife’s ambition and betrayal as they seek to usurp Scotland’s king and sit on his throne. This tragedy is famous for the fraught and frightening dynamics at the center of its marital namesakes, a couple that will push each other, denigrate each other, and ultimately abandon each other on their ascent. For the first three seasons of Succession’s run, Shiv (Sarah Snook) was the partner nearest to winning the throne, and the couple’s backroom dealings, furtive conversations, and strategic betrayals of family and each other were aimed at seating her on it. But beginning with the Season 3 finale, Tom (Matthew Macfadyen) began to seek power for himself. After a season of the two of them professionally at odds and trapped in a quagmire of desire, disgust, and Bitey matches, Shiv’s machinations ultimately crown her husband as the victor, fulfilling her “Lady Macbeth, redux” prediction. The final shot of the couple in their car, coldly touching hands in an approximation of formal regality, corporate bodies strewn in their wake, brings to mind the bloody ascent of the Macbeths — temporary as it may be.

Comparisons Can Be Drawn Between Kendall and 'Richard III'

But that’s not all. There is a strong strain of Richard III (technically a history play but often called a tragedy) in this final stretch of episodes, in which the death of a monarch creates a power vacuum that the eponymous Richard fills on the stabbed backs of the many allies, enemies, and family members he betrays — only to be supplanted at the end by an underdog victor. Richard murders his way through his immediate family and extended foes, thinking nothing of casting aside anyone who presents even a mild inconvenience. The tragedy of Kendall is his active choice to go down the path of “one head, one crown,” whether by readying Hugo (Fisher Stevens) to undercut his siblings, abandoning his children (like Richard murdered his two young nephews), attacking his brother, or driving away his ex-wife (as Richard murders his own spouse). By the time Richard III sits on the throne, his hands are so bloody with betrayal they can hardly hold a sword, and his allies abandon him to death on the battlefield — just as Kendall watches Jess (Juliana Canfield), Rava (Natalie Gold), and Shiv leave him and doom him when he needs them most.

Even 'Hamlet' Plays a Role in 'Succession's Themes

There are even elements of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy of succession, Hamlet, in Kendall’s series-long struggle to either make his father proud or to remove himself from his father’s influence. But Hamlet isn’t seeking power — it’s his uncle Claudius’s betrayals that have plunged Denmark and the royal family into disaster. Claudius’s ambition results in the destruction of the family, but also in something that most clearly parallels Succession: the slow and steady march to victory of a rival Scandinavian. Though we know Fortinbras of Norway has been inexorably marching on Denmark throughout the play, by the time he arrives to take the Danish throne, there is no one left to oppose him. They have done themselves in and handed him the crown — just as Matsson (Alexander Skarsgård) ultimately ascends more through the Roys’ turmoil than any action of his own.

But none of these are perfect fits — in the end, Kendall isn’t seeking to avenge his usurped father, as Hamlet is, and his Richard III only gets close enough to the throne to playact in it. Succession has no Cordelia, Lear’s favorite daughter and perhaps the only innocent in the play, the only one operating from altruism and sincere love for her misguided father. And in Macbeth, the central couple has no heir, no children to continue their bloodline; their vicious pursuit of power is for themselves alone. But Succession’s Shiv is pregnant, something Roman (Kieran Culkin) uses against Kendall in their breathtakingly cruel climactic fight. While Shiv and Tom do cut a chilling figure as the conniving, corroded couple finally in power, and despite the dynastic heir growing in her belly, that’s not where Shakespeare’s play ends — Macbeth ends with the couple dead, undone by their own betrayals. We don’t need one of the play’s Weird Sisters to portend what fate might await them once Matsson has fully wrung out his “pain sponge” Tom and discards him like so much other Waystar trash.

Ultimately, It's All The Plays at Once

But finally, when all is said, done, slapped, and voted, it seems that the show does indeed circle back to its beginnings in King Lear — and not only because of the preoccupation, both comic and terrifying, with the delicacy of eyes (or as Caroline [Harriet Walter] calls them, “Face eggs”). The king is dead. From a business perspective, his three children are too. Roman speaks the truth with brutal clarity in the way only Lear’s famous fool can: “We are bullshit…we are nothing.” And ultimately it’s Albany and Edgar left standing — the former the husband of one of Lear’s children, underestimated and dismissed from the beginning as weak, and the latter a figure outside the immediate line of succession who has played a hapless madman throughout. Tom-Albany and Greg-Edgar rule over the smoking ruins, the body-strewn battlefield. But for what? “We’re bullshit,” wise fool Roman said. Are the “victors” any more real for still standing?

And this, ultimately, is the lesson of all of Shakespeare’s tragedies of succession: The pursuit of power eats you alive from the inside. The poison drips through. And there is no satisfaction, no sating the need to cut through your own heart to put the crown on your head. But once you’ve finished hollowing yourself out, there will always be someone waiting in the wings to cast you aside. Shakespeare’s tragedies of power start with a set of seemingly stable relationships: Lear and his children in a delicate dance of deference and authority in which everyone knows the rules. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in a loving and relatively equal marriage. Richard III’s brother securely on the throne. They all devolve into infighting, violence, betrayal, and devastation. And they all end with an outsider on the throne and the main combatants out of the game, destroyed by their own avarice and the ruthlessness of those closest to them.

In that way, it doesn’t matter which play Succession ultimately modeled itself on — it was all of them. Over the course of four mercilessly written seasons, the family moved from (admittedly awful) stability to disarray through hubris, abuse, and the insatiable, bottomless need for power. The familial conflict has global ramifications, as both Logan and his children do their damnedest to plunge America into fascism for the sake of their ambition. An empire falls, ruled over not by someone with the birthright to the throne but by those with the cunning to exploit the siblings’ self-immolation. Succession always was and would always be a Shakespearean tragedy; the only question was which and when. For as the victorious Richmond says at the end of Richard III, surveying the damage done by all-encompassing ambition, “The brother blindly shed the brother's blood, / The father rashly slaughter'd his own son.”

All episodes of Succession are available to stream on Max.