Zack Snyder’s Justice League, or “The Snyder Cut,” is set to hit HBO Max on March 18th, ending a nearly four-year fan campaign to restore some phantom original version of the 2017 film. After Warner Bros. tasked Joss Whedon with rewrites and comedic punch-ups, the Avengers director took over reshoots as well. Snyder, having recently suffered a family tragedy, no longer had the will to push back according to recent reports, and decided to step down. The result was a 2-hour Frankenstein’s Monster of a movie being released in cinemas. The version set to release this month — after a day of reshoots, and a budget which ballooned to $70 million — doubles that 2-hour runtime, and appears to darken the tone considerably.

If all this feels familiar, it’s because Superman II (1980) followed a similar trajectory. Original director Richard Donner was replaced by Richard Lester mid-production, and a fan campaign eventually led to the release of Donner’s more serious vision, albeit a full 26 years later.

The way these two versions compare to one another, and to various fan-edits of the movie, is just as intriguing as the tumultuous history that led to Donner’s firing. Hot off the success of horror drama The Omen (1976), Donner was hired to direct Superman: The Movie (1978) from a script by Robert Benton, David and Leslie Newman, and The Godfather author Mario Puzo. It became a landmark for the superhero genre and for Hollywood in general, entering the history books as the most expensive movie ever made. The budget was an estimated $55 million — about $250 million today — and father-son producing duo Alexander and Ilya Salkind had also decided to film the sequel concurrently. This was a rarity at the time, though it’s something the Salkinds were forced to attempt on their back-to-back Three Musketeers and Four Musketeers films in 1973 and 1974, after failing to meet the release date of their originally intended single feature.

Production on Superman: The Movie and Superman II began in March 1977, but tensions soon arose between Donner and the producers, i.e. the Salkinds and their frequent collaborator Pierre Spengler. They claimed Donner had gone millions of dollars over-budget. Donner, however, maintains he was never given a budget to begin with.

In July, the Salkinds brought Three and Four Musketeers director Richard Lester aboard as an uncredited producer and second-unit director. Things had quickly devolved between Donner and the Salkinds, who were no longer on speaking terms by this point; Lester, therefore, was also hired as their go-between. As production went on, Lester even suggested that Donner shift his focus entirely to the first film, with a significant portion of Superman II already in the can. Ilya Salkind claims Donner had shot “50 to 60 percent” of what he’d intended for the sequel. Most reports estimate “around 70 percent.” Either way, Donner would never return to shoot the remainder.

On December 15th 1978, Superman: The Movie was released domestically to critical acclaim and box-office success. Two days later, Marlon Brando (who played Superman’s father Jor-El) sued the producers for $50 million, claiming not to have received his promised 11.75% back-end cut. Despite having shot scenes for the sequel, the Oscar-winning actor was subsequently removed from the film.

Shortly thereafter, Donner’s feud with the producers went wildly public. At a Christmas party in 1978, Spengler told Variety journalist Army Archerd that he looked forward to resuming production on the sequel despite his disagreements with Donner. When asked to comment on the story, Donner responded: “If he’s on it — I’m not.”

Donner was inevitably let go from the project. By early 1979, the search for a new director had begun, and the Salkinds approached Guy Hamilton, helmer of several Bond films including Goldfinger (1964) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). Hamilton, it’s worth noting, was the original choice to direct both Superman films back in 1975, when the production was gearing up to shoot in Rome. However, owing to an outstanding obscenity lawsuit against Marlon Brando and those involved in The Last Tango in Paris (1972), Brando was unable to shoot in Italy, and the production moved to England in late 1976. Hamilton, being an English tax exile, was only allowed in the country for 30 days a year, and so the job soon fell to Donner.

It wasn’t meant to be for Hamilton this time either; he was unavailable for the sequel, and the search continued. By the time production on Superman II was set to resume, producer Richard Lester had seen through his directorial commitments on adventure film Cuba (1979), and so in March 1979, he stepped out from the uncredited producer role he had been hired to 20 months prior, and officially took the director’s chair. To solve the Jor-El problem stemming from Brando’s suit against them, the Salkinds replaced him with Susannah York, who had previously played Superman’s Kryptonian mother Lara. The film’s production woes, however, were far from over.

Cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth had died in October 1978, so a replacement needed to be found; Donner wanted to use Unsworth’s longtime camera operator Peter MacDonald, but Lester eventually hired Robert Paynter to mimic the garish color scheme of the comics, and eliminate any idealized, Norman Rockwell influence. Shortly thereafter, the film’s production designer John Barry died in June 1979, after collapsing on the set of The Empire Strikes Back (Peter Murton was his replacement). Filming was set to resume in July, but Superman actor Christopher Reeve had already committed to Jeannot Szwarc’s romantic time-travel drama Somewhere In Time (1980). The Salkinds sued Reeve for breach of contract.

Upon re-negotiation, Reeve demanded more creative control, since he maintained reservations about the script following Donner’s departure. Filming eventually resumed in September and was completed six months later in March 1980, over a year behind schedule. Along the way, continuity errors due to changes in the actors’ appearances (and in the case of Lex Luthor actor Gene Hackman, his unavailability altogether) meant elements of Donner’s footage had to be incorporated into scenes shot by Lester. Add to that the fact that Lester used a three-camera setup as opposed to the traditional single-camera — thus frustrating the actors, who rarely knew when they were being filmed in close up — and the result is a production nightmare.

The credits of Superman: The Movie ended with the words “Next Year: Superman II,” but the sequel wouldn’t open in America until the summer of 1981, six months after its Australian release, and a full two and a half years after the first film’s end-credit promise.

Superman II was generally well-received. Roger Ebert praised it just as highly as he did the original, and though it made about $100 million less than its predecessor, it was still a box-office hit, becoming the highest domestic earner of 1981 and the third-highest worldwide. Lester would go on to make Superman III (1983), while Donner found success elsewhere with beloved films like The Goonies (1985) and the Lethal Weapon series (1987-1998). While various broadcast edits of Lester’s version (like those seen in Europe and Australia) would feature more of Donner’s footage, the book on Superman II had been mostly closed.

That is, until 2004.

Decades after Superman II’s production kerfuffle, the landscape of film fandom had evolved thanks to the internet, home video and the success of superhero films like Spider-Man (2002) and the Donner-produced X-Men (2000). “Director’s Cuts” and “Special Editions” had become more commonplace, beginning with Ridley Scott’s new cut of Blade Runner, which was given a theatrical release in 1992, and the Special Editions of the Star Wars Trilogy in 1997. The most notable development, however, came in 2001 in the form of the DVD Special Edition of Superman: The Movie, cobbled together and restored (with Donner’s input) from old broadcast versions, which were made slightly longer than the original, since TV stations paid for the film by the minute.

By this time, fan websites and forums had become the new water cooler, where dedicated followers of various franchises could discuss these changes in-depth, and compare their favorite versions. And so, in May 2004, Planet of the Apes fan-blog The Forbidden Zone began a letter-writing campaign in an effort to get Donner’s version of Superman II released in time for the film’s 25th anniversary. The blog suggested writing to Warner Bros. all at once — rather than spread out over a period of time — on June 19th, the film’s original US release date.

While this sort of fan coordination bears resemblance to the #ReleaseTheSnyderCut movement, whose followers often get topics of their choice trending on Twitter, a more striking similarity between them is they both picked up steam after apparent confirmations of an alternate version from within the production’s ranks. The Forbidden Zone’s press release (and subsequent write-ups by popular fan websites like Ain’t It Cool News) cited a 2004 Starlog Magazine interview with Lois Lane actress Margot Kidder, in which she said: “There’s a whole other Superman II in a vault somewhere, with scenes of Chris and me that have never seen the light of day. It’s far better than the one that was released.”

Of course, neither the “Snyder Cut” nor Richard Donner’s Superman II existed in anything resembling completed form. But while there was no official word on Zack Snyder’s Justice League until three years into the campaign, proponents of a Donner Cut received a response from Warner Bros. almost immediately, though perhaps not one they were hoping for.

Jim Cardwell, President of Warner Home Video, responded to several fan emails in the summer of 2004: “Warner Home Video is supportive of an extended version of Superman II on DVD. However, there are complex legal and creative issues that need to be resolved before the film can be re-released. Warner Home Video is presently addressing these issues.” The legal issues in question likely referred to WB being unable to use Marlon Brando’s likeness, owing to the original lawsuit. As for the creative issues, Donner had, in fact, been approached to work on a new cut of the sequel in 2001 — shortly after revamping the first film — but he had refused the opportunity. “Quite honestly, I was done with it,” he said. “I was finished with it. I had such a bad experience with the Salkind family that I just didn't need it anymore.”

However, the letter-writing didn’t stop there. In a 2006 interview with Amazon, George Feltenstein, Senior Vice President of Warner Home Video’s Catalog Marketing, revealed his department had been getting letters “for years and years and years” begging them to release the Donner Cut of Superman II.

Creating a “Donner Cut” of the film would be no easy feat. Too much time had passed to shoot new footage with any of the still-living actors, and Donner himself had already disparaged the idea. If it were to somehow come to fruition, the task would not involve reshoots, but would fall heavily on the post-production process — which is where editor Michael Thau enters the story.

Thau, who once served as Donner’s assistant on The Goonies (and had a producer role on the first two Lethal Weapon films) had previously worked on the DVD restoration of Superman: The Movie. In order to create this version in 2001, Thau had unearthed a significant amount of footage of the first film in a vault in England — six palettes, in his estimation.

Once the fan-campaigned picked up momentum in 2005, Thau was approached by Warner Bros. once again, this time about assembling the still non-existent “Donner Cut.” Unbeknownst to fans, circumstances had changed. The studio informed Thau that a deal had finally been struck with Marlon Brando’s estate in order to use his voice and likeness in the upcoming sequel/reboot Superman Returns (2006), which also meant footage that had been previously shot with Brando could be re-incorporated into a new cut of the 1980 sequel. And so, back to the vault Thau went — where he discovered another six palettes of unused footage from Superman II.

After months of sorting through film reels — and through the script supervisor’s old continuity sheets — Thau began re-editing the film under the supervision of creative consultant Tom Mankiewicz, who had served as a writer and creative consultant on Superman: The Movie, and had also done uncredited rewrites on the sequel. Shortly thereafter, despite having distanced himself from the project numerous times, Donner became directly involved, and provided Thau with notes and feedback as he worked on the film. Slowly but surely, the “Donner Cut” became a reality.

This wasn’t to be a re-tooled version of the theatrical release, but rather, a mostly new film cut from the original negatives, comprising alternate takes edited by Thau, as well as scenes edited by Stuart Baird during his work on Superman: The Movie. Owing to constraints, the creators even resorted to using screen tests Donner had shot with Reeve and Kidder, for a scene he never got to film. Footage from the theatrical release (edited by John Victor Smith) was used as well, resulting in something resembling Donner’s original intent, but augmented by the version audiences had seen in 1980-81. The music, similarly, was a hybrid of John Williams’ compositions for the first film — Williams was unavailable to record new music, since he was busy on Star Wars Episode III (2005) — and bits and pieces of the score by Superman II composer Ken Thorne, who had rearranged Williams’ work for the theatrical release.

On November 28th, 2006, Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut was finally released on DVD.

The broad strokes of both versions remain largely the same. After a brief recap of the prologue in Superman: The Movie— in which Kryptonian villains Zod (Terrence Stamp), Ursa (Sarah Douglas) and Non (Jack O’Halloran) are banished to the Phantom Zone — the sequel picks up where the first film left off. Lois begins to suspect that Clark Kent might be Superman, Lex Luthor escapes from prison, and the Kryptonians make their way to Earth after a nuclear blast sets them free. Clark, upon revealing his identity to Lois, takes her north to his Fortress of Solitude, where he gives up his powers in order to be with her. Upon returning to Metropolis, the de-powered Clark catches a glimpse of Zod’s destruction and returns to the Fortress to regain his abilities. With Luthor’s help, the Kryptonians track down Lois and use her as bait; Superman returns to stop them and a fight ensues, only it’s a losing battle for the Man of Steel, who finally lures the trio away from civilians by returning to the Fortress a third time. While there, he pulls a switcheroo and fools the villains into depowering themselves. The day is saved, but Superman realizes the danger he poses to Lois, and — using his strange, nondescript powers — he erases her memory of his dual identity, sacrificing his happiness for the greater good.

Both versions are anchored by Reeve’s sincerity, but they differ in a couple of major ways. Lois, for one, has a more active role in the theatrical cut, which begins with her jumping into danger to cover a story about terrorists holding tourists at the Eiffel Tower hostage with a nuclear bomb. It’s while disposing of this bomb in space that Superman accidentally frees Zod and his crew, though in the Donner Cut, their escape is framed as a result of him saving the world from nuclear missiles at the end of the first film. Instead of the Paris threat — a scene which doesn’t exist in Donner’s version — the Earth-bound story begins in the Daily Planet newsroom, where Lois begins to suspect Clark’s ruse from her very first scene, thus retaining some of the quick-talking, screwball elements from Superman: The Movie. In the theatrical cut of Superman II, Lois’ suspicions don’t begin until she and Clark travel undercover to report on a honeymoon suite racket at Niagara Falls.

The tug-of-war between these two versions makes for a fascinating comparison. In the theatrical, Lois has far more agency at first, and there are moments which flesh her out as a flawed, messy and delightfully contradictory character, who chain-smokes while pressing her own orange juice in her office, citing health reasons. She loses some of these traits and quirks in the Donner Cut — which, at 116 minutes in length, is about 11 minutes shorter — but Donner also makes her a much smarter character, and Superman’s intellectual equal, even though she lacks the flaws and idiosyncrasies of her theatrical counterpart.

Another result of Lois being more fleshed out in the theatrical is that her gooey romance with Clark gets more screen time. They share more conversations and more interpersonal moments, especially on the Niagara trip. But in this version, Lois also ends up confirming Clark’s dual identity entirely by accident, when he trips and falls hand-first into a fire but escapes unscathed. The smarter Lois of the Donner Cut plays a more active part in uncovering his identity, in a sequence assembled from both actors’ screen tests, since the scene was never filmed. To get Clark to admit to being Superman, Lois shoots him and he shrugs it off (though he’s unaware that she’s using blanks). She seems to lose agency as the theatrical cut goes on, but she gains it in Donner’s version, despite having less to do.

While the theatrical cut of Superman II establishes a more intimate dynamic between its leads, the Donner Cut has a more emotionally complex Superman story at its core. In the theatrical, the projection of Lara in the Fortress of Solitude doesn’t really provide any reason why Superman must sacrifice his powers in order to be with Lois, and when he realizes he needs them back, he regains them just as easily. This is where Donner’s vision most departs from Lester’s.

In 2006, fans were first treated to scenes between Reeve and Brando wherein Clark displays something of a selfish streak. Jor-El insists that Clark continue serving humanity, but Clark is torn between this duty and finding true happiness for the first time. This subplot allows Reeve to put Clark’s anger and internal conflict on display; it bears an interesting resemblance to a scene in Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (1993) where Bruce Wayne confesses a similar conflict at his parents’ grave. Both sequences get to the heart of their respective characters’ dualities, and the ways their missions to serve humanity clash with their ability to lead fulfilling personal lives. Furthermore, when Clark needs his powers back in the Donner Cut, he has to make a tangible sacrifice in order to regain them. The energy needed to restore his abilities will permanently take Jor-El’s projection offline, thus cutting Superman off from his heritage, and all the lessons his father still needs to impart from beyond the grave.

Donner’s Superman is the more emotionally engaging of the two, but his straight-faced approach forfeits some of the silliness and abstract moments which made the Lester version click. In Donner’s version of the depowering, Clark enters a crystal chamber and the scene crescendos in a hail of explosions which destroys the Kyrptonian computer. Lester’s vision in simpler — Clark steps inside, the lights change, and we hear some mechanical whirs before he steps out again — but it features a brief moment where, as Clark exits the chamber in his human garb, he leaves behind a fading image of Superman in all his red, blue and yellow glory. It makes far less logistical sense, but it’s a perfect visual and emotional representation of what he’s giving up (even though the “why” of this sacrifice is nonexistent here).

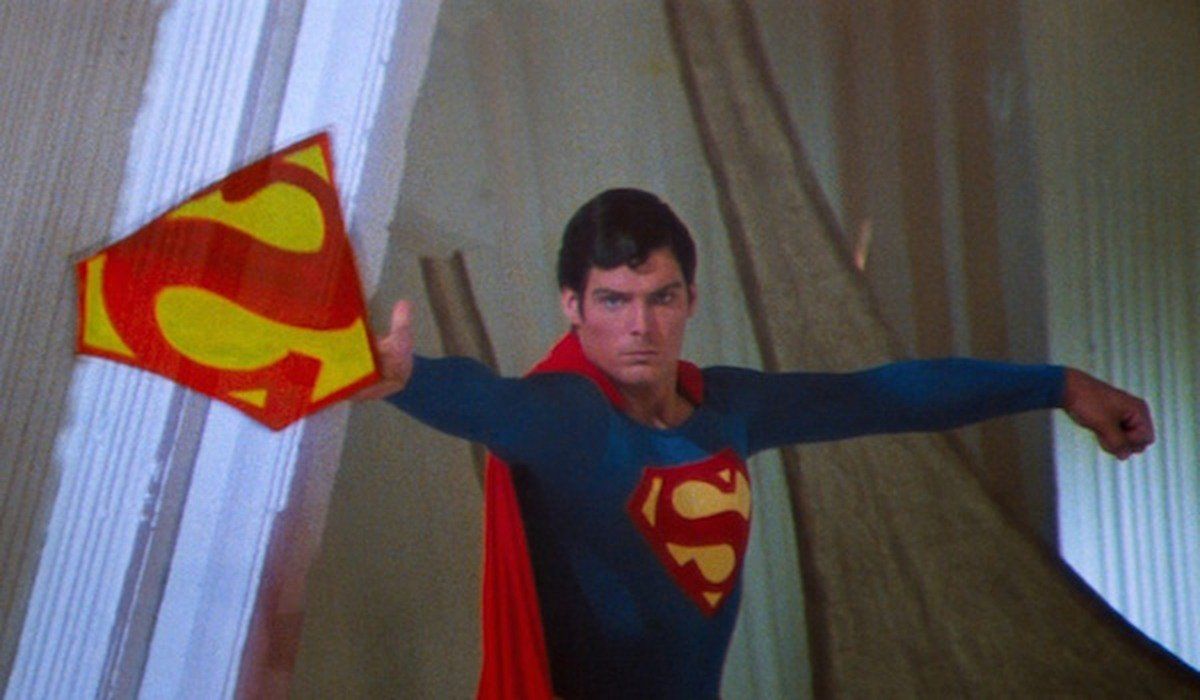

Then again, logistics were hardly ever a concern for Lester. Donner’s use of establishing shots helps create a real sense of space, which the Lester version lacks. But what it loses in geography it more than makes up for in unapologetic whimsy. The theatrical version features a second climactic fight after the one in Metropolis, wherein Superman and the Kryptonians put all their strange and fantastical powers on display in the Fortress of Solitude. Superman grabs his own logo off his chest and throws it at Non, and it inexplicably expands into a cellophane blanket. The fight also features all four superhumans teleporting and creating copies of themselves; it’s complete nonsense, but has a uniquely childlike allure. Donner’s version, meanwhile, features no physical confrontation whatsoever in the Fortress, and skips straight to Clark’s depowering ruse.

Donner takes the story and characters more seriously, and his mythological approach was disparaged by Lester, who called it “David Lean-ish,” since Lester himself tended towards the inherent silliness of the Superman mythos. This is especially apparent in Lester’s version of the Metropolis fight, which features extended sequences of civilian pratfalls. The Donner version of this fight makes it feel like the people are in far more danger, which certainly works for a story where Zod uses Superman’s love for humanity against him (“No, don’t do it! The people!” Superman yells, as Ursa and Non lift a bus full of passengers). But it’s difficult to pin down which approach, if any, is ostensibly “better.” Comparatively, the two cuts take wildly different approaches to not only the same story and characters, but in some cases, the exact same footage. The Lester cut is “better” at levity. Lester’s Non, for instance, comes off as an overgrown baby constantly seeking Zod’s approval with his violent antics, but these brief moments and comedic reaction shots are lost in the Donner version. Meanwhile, Donner’s cut is “better” at telling a serious, straightforward story of mythological sacrifice.

There is, perhaps, no ideal official version of the film, since each cut seems to lose something fundamental no matter what it actually gains. However, there also exists a third major edit, dubbed by fans as Superman II: The Restored International Cut, which functions as a kind of hybrid between the Donner and Lester versions. In 2004, fans sought to recreate, as best they could, the nearly 2.5 hour broadcast edition of the film which aired in Europe and Australia, using various fan-submitted sources like VHS recordings. Fans even created their own DVDs of this version, though Warner Bros. soon brought down the legal hammer (it’s now only available if you know where to dig online). There’s plenty in this broadcast version that feels extraneous, but it also features just as much that enhances the story. For instance, it includes the famed alternate ending where, instead of being left for dead, Zod, Ursa and Non are arrested after plummeting to what many assumed were their deaths in the Fortress. However, even the broadcast version was forced to sideline Superman’s sacrificial arc from the Donner Cut, since this footage had not yet been made available.

Though what is perhaps most interesting about comparing the Lester and Donner cuts is trying to decide which makes for “better” Superman canon in the grand scheme of things. They’re largely the same story at the end of the day, but where they diverge the most is their endings. In the theatrical cut, Superman inexplicably erases Lois’ memory using some sort of psychic kiss. The iffy ethics of this decision aside, it makes for a unique conclusion that firmly establishes Superman’s trajectory as a man forced to walk a lonely path in service of humanity. The Donner version, however, features Superman flying around the Earth as he did at the end of the first film, and undoing, through time travel, all the events of the sequel including Lois learning his identity.

The result is similar, in that Lois no longer knows who Superman really is, but had this ending been used in the theatrical version, it would have fundamentally altered what this series was about (and, in all likelihood, altered the Superman mythos in general, given how these films influenced the comics). Had Superman flown around the world a second time in 1980, it would have meant that the Superman franchise, at its core, was about a Godlike being who could turn back time on a whim — instead of this being a one-time decision he makes in Superman: The Movie while wrestling with Jor-El’s instructions about not meddling with human history.

While it seems odd that Donner would opt for the exact same ending in both films, this was actually a result of their topsy-turvy production. Originally, only the sequel was meant to end this way, but shooting had commenced without an ending for the first film in mind. Brando’s original suit alleged that Warner executives decided to simply use the time-travel sequence to close out the first film instead, leaving Donner to come up with a revised ending for the second; Donner would eventually confirm this in an interview in 2016.

Donner re-incorporating the time-travel results in another oddity. At the end of the theatrical version, Clark returns to a diner where, earlier in the film, a rude and belligerent patron had harassed Lois and physically assaulted him, resulting in Clark bleeding for the first time, since he had given up his powers. With his abilities restored, Clark teaches this patron a lesson by sliding him across the counter in the closing scenes. Strangely, this version of the ending remains intact in the Donner Cut, despite Superman having turned back time and erased the events of the last few days. The result is Clark essentially showing up to bully a man who has yet to do anything wrong!

Had Donner stayed on to complete the sequel as planned, his version would have, in all likelihood, not featured a second time-travel conclusion, and so this closing diner scene would have continued to make sense, as it did in Lester’s version. Donner’s 2006 re-assembly, therefore, allowed him to restore a vision of Superman II that was unconstrained even from the reality of making both films back-to-back and the compromises therein, and so it ends up occasionally disconnected.

However, what may seem like an error or poor planning takes on new meaning in light of Donner’s own thoughts on the subplot. In 2001, after initially turning down the Donner Cut, he spoke bitterly about Lester having taken credit for the diner scene — which Donner not only shot, but in which he makes a cameo appearance. “There was an interview, and the director who finished the picture talked about how important that scene was to him as a filmmaker,” he said. “I wanted to say, ‘You son of a bitch, you didn't do that scene. Not only didn't you make that scene, I'm in it!’” The payoff may not be artistically sound, but the decision to keep this subplot intact feels like a personal statement.

While it may not have been Donner who kicked off the restoration — or even Thau for that matter; the fans’ letter-writing was probably the biggest catalyst — Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut remains one of the rare Hollywood success stories where a fired director was able to return to the vault and re-assemble his vision decades later, for better or for worse. Whether or not it’s the best version of the film will likely always be up for debate, but it also stands to reason that the debate itself is now an integral part of Superman’s cinematic lore.

Between the Donner Cut, the theatrical cut, various TV versions including the Restored International Cut, and over a dozen hybrid fan edits which pick and choose each creator’s ideal combination of footage, Superman II remains something of a white whale amongst dedicated Superman fans, for whom a perfect version of the film seems to exist only their imagination. Now, with all this footage out there in the world, and with audiences who have the ability to reassemble it as they please, coming close to some subjective “perfect” Superman II feels much more possible than it did in 1980, when watching a man fly had only just become a reality.

Then again, perfection is a chase that may never end when it comes to cinema, no matter how many permutations of a film are re-edited and #Released into existence. At the end of the day, it was still the theatrical Superman II, with all its flaws and lucid charms, which audiences first adored, and which continued to cement the Man of Tomorrow as a glowing fixture of popular culture. For all the series’ fantasy and special effects, few moments can match the human quality of Christopher Reeve’s smile, equally earnest and debonair, as he rescues Lois from a falling elevator in the theatrical version, before quipping: “I believe this is your floor.”