Open on a field of stars. A massive spacecraft drifts into frame with a chyron designating function. In it, we see a juxtaposition of mundanity and an extraordinary setting: shipboard table tennis, astronauts watching cartoons. This is the good stuff, familiar comfort originated from the original Alien. This homage to space horror may be to the credit of a promising derivative like Supernova, but it’s then too generic to distinguish among the early-2000s space craze. Its year of release also saw Mission to Mars, Red Planet, and Titan A.E., none of which succeeded at the box office or with critics. Pitch Black fared better, but Jason X, Ghosts of Mars, and the Solaris remake were just around the corner.

Despite A-list talent, Supernova rates as one of the most profound of these turkeys, grossing what would be iffy numbers for a far more terrestrial picture. Maybe audiences were exhausted by the spaceships and the chyrons and the mundanity. They’d been burned too many times watching explorers take an hour to gear up and set out into the vast unknown, only to encounter something anticlimactic. Supernova should have been different. In fact, there were a lot of reasons why it should have succeeded. Despite what the credits say, it was directed by Walter Hill, the one director more closely associated with the Alien series than James Cameron or Ridley Scott, and it began life as a project by xenomorph designer H.R. Giger about Satan in space! And any film bearing the words “Starring Angela Bassett” is worth a look, right? So what happened?

Unfortunately, these appealing details are deceptive. First, Walter Hill’s association with Alien has always been a curious thing. Despite being intimately involved in the drafting of the original Alien, as a director himself, he specializes in neo-westerns about tough dudes. It’s difficult to say whether a Hill-directed Alien would’ve worked or not, and Supernova provides us no answer, being also directed by Jack Sholder and even Francis Ford Coppola. Two directors might be a creative partnership, but three sounds like studio interference. As for H.R. Giger's involvement, well, there is no spacefaring Satan to be found in the final product.

'Supernova' Started Life as Something More Original

In 1990, horror director William Malone, who gifted us one of the notable Alien knockoffs, Creature, was commissioned by Imperial Entertainment to develop a sci-fi project. Malone and Imperial producer Ash R. Shah turned to Giger to design the particulars of what was then entitled "Dead Star." The resulting concept art is cataloged on the blog Alien Explorations. Years before Hellraiser: Bloodline and Event Horizon, Dead Star imagines what happens when that steadfast boundary between space and hell is punctured, unleashing a Satan with enough xenomorph texture to possibly trigger trypophobia. When queried on the holes, apparently Giger replied, “I don’t know, I just needed to make some holes.”

At this stage, the story was about the recovery of an alien artifact in deep space, a “Thanatron,” which could reanimate the dead and open a gate to hell on Earth. With Giger’s sketches in hand, Malone went looking for a buyer and, after several years of disinterest by studios, lost track of the project, only to hear later that MGM bought the script. Their first order of business was a rewrite, with not a few screenwriters. One of the later drafts even recalls Event Horizon down to the space-folding ship traveling to the end of the universe. When James Spader was cast, he had enough pull to bring on Walter Hill, who did further rewrites. This appears to be business as usual, but it begs the question, if MGM allowed such a dramatic transformation of the story, why were they interested in Dead Star to begin with? Whatever that initial interest, it was eventually halved along with the budget, excising a small army of visual effects shots. What began as the admittedly expensive-sounding “hell on Earth” premise became the comparatively underwhelming Supernova, but not before Walter Hill quit.

Studio Interference Turned 'Supernova' into a Mess

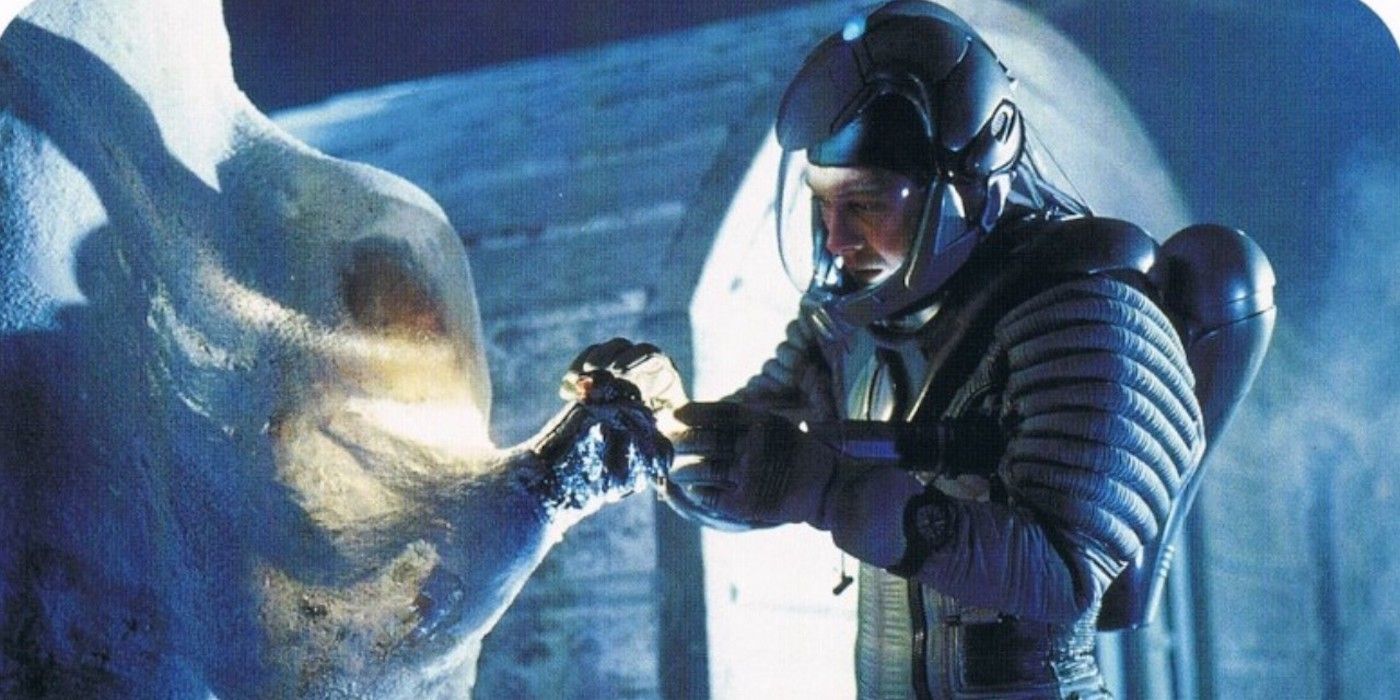

After disastrous test screenings, MGM board member Francis Ford Coppola was brought in to supervise reshoots and alterations. Maybe the most curious is the transformation of a sex scene between two characters into a sex scene between two other characters. Faces may have been cut and pasted onto bodies. The most egregious, however, is the trimming of the effects contributions of Patrick Tatopoulos, leaving a villain with slight facial disfigurement instead of Giger-esque body horror. This is Karl (Peter Facinelli), who the astronauts retrieve on the other side of a distress beacon and a "dimension jump." In this final version of the story, the Thanatron is an unnamed artifact, probably for the better. Karl, a ghost from Dr. Kaela Evers's (Angela Bassett) past, had discovered it along with a group of now-dead space pirates. The artifact can grant superpowers to those lured to its glow. Superpowers and insanity, of course, lead Karl on a killing spree through the ship.

The shipboard AI is somehow able to deduce that the artifact is a “creation device,” essentially a murderous Monolith that species who develop spaceflight are meant to bring home and turn their sun into a supernova bomb. “All the principles of Darwinian evolution,” Dr. Evers says. “Whoever they are, they’re as smart as God and a lot less nice.” So what is this all about? With 2001: A Space Odyssey as a thematic guide, perhaps it's something about overcoming the hubris of mankind in this final arena, of reconciling that there are places we aren’t meant to go. But these astronauts weren't operating with hubris. And what does all this talk about God and creation have to do with the film's second-act focus on a love triangle or Evers' mysterious relationship with Karl?

'Supernova' is a Cautionary Tale

In one scene, Wilson Cruz’s character Sotomejor (spacebound here long before Star Trek: Discovery) tries to get the AI to vent Karl into space, but she, the AI, cannot harm a human. Instead of invoking the second part of the first law of robotics, “a robot shall not … by inaction allow a human to come to harm,” Sotomejor attempts to get her to run a simulation wherein he’d be dead and she'd feel bad, given that she had awakened him to play chess in the opening scene. Long story short, there's no venting, and it’s a nice miniature of the whole: a dreadfully complicated nothing. And yet, with all the reshoots and directors cycling in and out, Supernova is surprisingly coherent, with few threads left to dangle. The problems began earlier, and no amount of “fix it in post” would’ve done the trick. This is a space horror movie without a monster, a slasher movie with muted, PG-13 kills. The production design and effects are nice, with ship interiors that wink at Giger, and James Spader is a natural with technobabble. And of course, Angela Bassett is the only actor who could make up for a film's general lack of everything. Her performance is lived-in and weary like she's constantly shaking bad memories from her head. After having seen Supernova, perhaps it's time for us to do the same.