The first time we meet Tallulah, she’s scrawled on her lover’s hand in a crude stick-n-poke tattoo. The second time we meet her, she’s swinging into a dilapidated van, swigging from a pilfered whiskey handle and urging said lover (now turned getaway driver) to speed away from the roadhouse they’ve been idling in front of. From the very beginning of Tallulah – a film whose title calls up both the roguish charm of the historical figure Tallulah Bankhead and the often irritating, persistently imperfect hero of Ellen Page’s Lu – we’re forced to spend time, intimate time, with a vagabond who prides herself on her ability to subsist on dumpster dregs and sleep in the back of her van rather than grow the often scarily permanent roots the world seems to require from the “functioning adult”. And from the very beginning, her predilection for detachment gets the better of her. Before Tallulah has any time to get off the ground, her would-be partner-in-crime takes off in the middle of the night, leaving Lu less the few hundred dollars the two had managed to pilfer away and with only a credit card emblazoned with a New York address, belonging to the ex’s mother, as her guiding north star.

In the city, with a quickly dwindling food supply and a vehicle that threatens to quit with each new shift of the gears, Lu makes a beeline into a swanky New York hotel in the hopes of finding abandoned room service to make her lunch (after drying up her supply of cheesey chips and other vacuum-packed delights). What she finds, instead, is a woman (Tammy Blanchard) seemingly ripped out of the Real Housewives playbook – sauntering around her painfully chic hotel room in full-body spanx as she neatly ignores her child, a toddler who wanders nude around the room – at one point ambling onto the balcony to which the mother only purrs chidingly, “Well, she needs to learn.” A dizzyingly quick escalation of events leads to Tallulah acquiescing to the mother’s puzzling demands for Lu to stay and watch her child (drawn in, no doubt, by the scads of jewels and wads of cash that litter the room) while she departs to gallivant about the city.

Of course, the film’s weakest narrative device is also the one that it hinges on, as a night of caretaking gives way to the realization that the child is parented with an all-too familiar neglect, and by morning, Lu finds herself hightailing it out of the hotel, baby in tow. A woman without a country (but with a toddler and an all-important credit card), Lu tracks down her ex’s mother (Allison Janney) – an uptight NYU type – and drops herself and the child onto her doorstep, insisting that the little one was a product of Lu’s relationship with her son.

Ellen Page, like Tallulah herself, is the real gem of the picture. Nearly a decade away from Juno, Page finds herself recalling a bit of that charmingly immature affect that served her so well so many years ago, but manages to imbue it with a sense of world-weariness and an often squelched willingness to love that only decades of disappointment might provide. And while some viewers will find it hard to warm to Lu with her constant deceptions and thieving, it’s Page’s performance that brings the dishonest girl on the page to its most empathetic end.

Allison Janney‘s performance here also recalls some of her best dramatic work. Still wildly funny – there’s a scene involving the sudden death of a turtle that Janney manages to make blisteringly hilarious – she reaches a new level of emotional exhaustion and personal ambivalence that helps to bring what could be an overwrought, uptight character trope into the realm of the real. But the biggest surprise here is easily Tammy Blanchard, who elevates her character well beyond the easy-to-despise pouty lips and crocodile tears of a mother feigning despair, to a broken and devastatingly lonely woman whose most basal fears (of being alone, unloved) can feel eerily similar to your own.

Sian Heder, Tallulah’s writer and director, made her name prior to this film by working on Orange is the New Black, so it makes sense to see Uzo Aduba appear as a quietly rage-filled child services worker brought in to locate the missing child. But she, like the men of the film (most notable of which are Zachary Quinto and John Benjamin Hickey) is given relatively little to do.

Narratively, the film is serviceable, though the central conflict of Tallulah’s dishonesty and law-breaking looms large here, like the poorly hidden deceit usually found in a hammy romantic comedy, albeit with far more swiftly-moving consequences. Heder is a first time director, and it shows: Tallulah is a bit of a technical mess – stuffed with narrative stops and starts that neither enrich characters nor fulfill the plot (the most notable of which includes an ill-advised relationship between Janney’s character and her apartment doorman), and the film is an ambling two hours when it should be a tidy 90 minutes. But Tallulah’s strength, quite like its central protagonist, is in its inexactness. Not quite magical realist farce, not quite gritty drama, Tallulah carves out a small, but well-deserved space in the “indie drama” category thanks to its laudable commitment to genuine emotion and a pointedly moving final scene. Never subtle, a bit larger than life, and with a thematic range that runs the gamut from light and cheerful to life and death, the film never seems to know quite what it should be. But hey, neither does Tallulah.

Grade: B

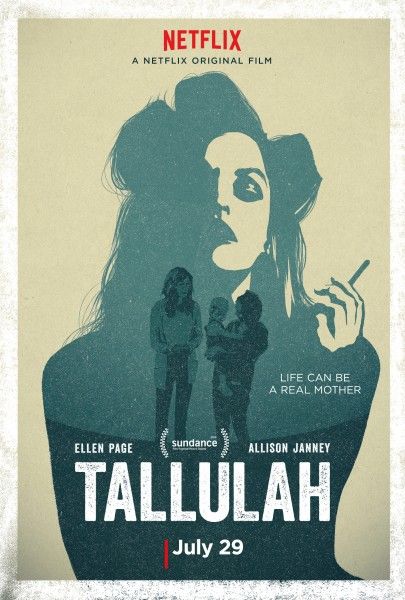

Tallulah premieres Friday, July 29th on Netflix.