Taxi Driver (1976), directed by Martin Scorsese, centers on the mental state of its protagonist, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), a recently returned Vietnam War veteran suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He lives in Manhattan and becomes a cab driver. Most of the film charts his devolution into becoming someone who commits several crimes and murders but also rescues a local child prostitute, Iris (Jodie Foster). While the ending proposes that Travis is now more mentally stable, Scorsese throws in an aesthetic grenade during the film's last seconds. The unnerving, hyper pigmented shot of Travis seeing himself in his rearview mirror, a wildness gripping him, makes us reconsider conceptualizations of healing and trauma experience.

Travis is an interesting antihero because his heart ends up in the right place, to protect someone being exploited, but he is drawn to violence as a means of fixing what he sees as a system of intensifying social and economic problems. His mental instability is furthered by him not having access to support or counseling. He plots to kill a regional political candidate, Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris). In a way, Travis’ philosophy is anarchist, but authentically, he is struggling with figuring out his identity in a new urban structure of a world, 1970s New York City, that he is navigating alone after experiencing the trauma of war on another side of the globe.

Travis has significant relationships with two women in the film, Iris being one, and the other, Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), a volunteer for Palantine. Travis hatches his plan to kill Palantine after a date with Betsy goes badly, and he causes a scene in her volunteer office. His systemic rage starts to merge with his interpersonal fury. With Iris, he hires her as a prostitute, using their time to try and convince her to leave prostitution. The crescendo of Travis’ violence builds quickly. He goes to a rally for Palantine to shoot him, but Secret Service agents see him with a gun. He gets away and goes later to find Iris. He kills her pimp, her client, and the bouncer at the brothel. Iris is safe.

Travis wants to kill himself at the end of the scene and does so imaginatively with a finger to his head. The implication is that Travis has no barometer to judge his actions that night as good or bad nor whether he is a force for positive change in the city or contributing to the corruption he despises around him. He feels his life could, or should, end.

The film’s ending offers, initially, positive conclusive touches to both of these relationships. For freeing Iris, he becomes a local hero and is not charged for the murders. He also hears from Iris’ father, who writes a letter thanking him for protecting his daughter. After Travis heals from his injuries, he is back to work as a cab driver and picks up Betsy. It is fair to say Travis has the upper hand in this conversation, from an emotional standpoint. Understanding his mind frame is important to contextualize that unbridled moment of self-identification that happens soon after their interaction ends.

There is a feeling Betsy still likes Travis, or, at least, has regrets about how badly things unraveled. She did like him, at the start. Knowing he saved Iris makes her feel closer to him again, as if they share similar morals and are on the same side. Travis, for his part, keeps a respectful distance from Betsy, no flirting, and even says he hopes Palantine wins. And, Travis has the last word. As Betsy struggles to say something about their past and ultimately asks how much money she owes him, Travis makes a show of clearing out the meter for her ride. With a smile, he indicates, in a way, their interaction was both something and nothing to him, but that now, he is free, not just from her, but from the emotional circus he got into with her.

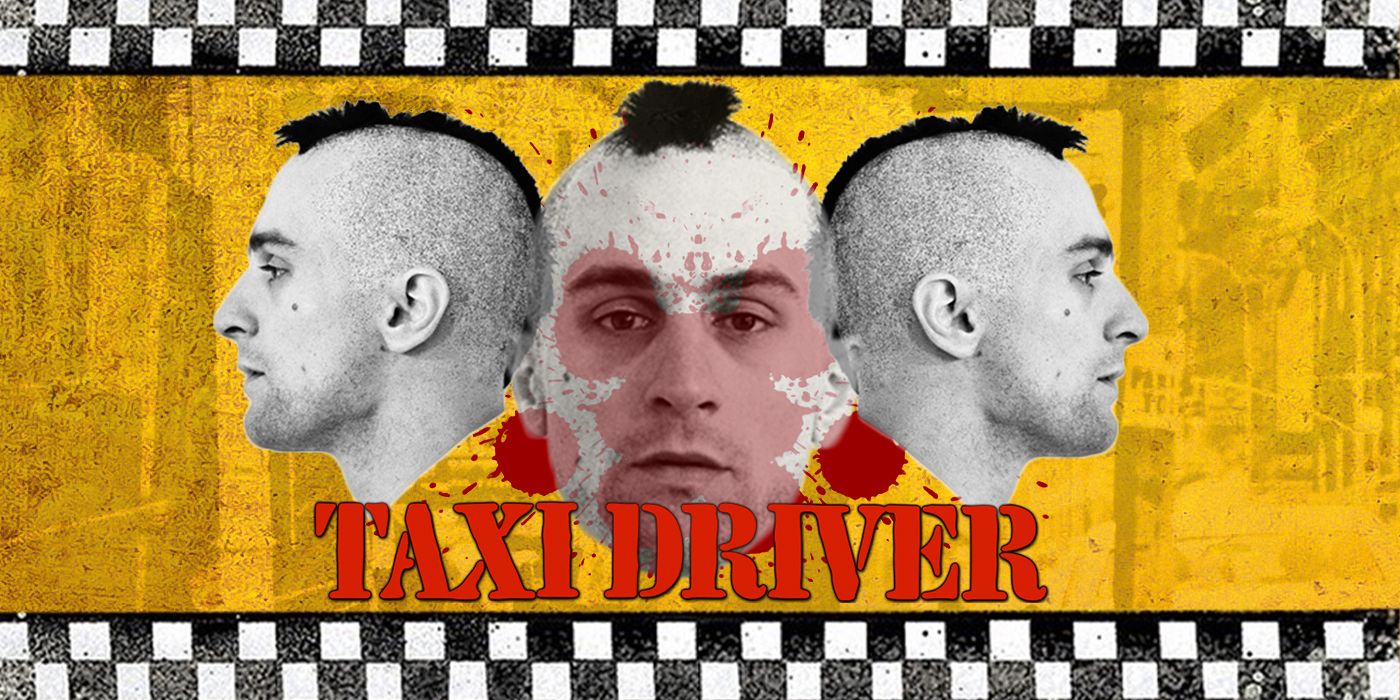

When Travis pulls away, he feels content. He is driving in the city, a place that maybe has become less frightening to him. As he continues driving, he glances in the rearview mirror and sees a portion of himself. His forehead, eyebrows, and eyes come into view and the scoring goes ominous. The camera darts around. Then, we’re back in Travis’ POV, seeing all the brightly lit signs on the streets, but something happened.

Travis saw himself but not who he expected to see. What is beneath his calm surface with a semi-ex? How comfortable is he looking at his past, nearly assassinating her candidate? It’s almost as if his polite manner with Betsy covers up his vestiges of rage, and his fear of that rage. When Travis sees himself, he sees the person ready to attack with a violence that surprises him, and that person is still him. With this dissonant ending, it's clear why Scorsese's Taxi Driver continues influencing filmmakers today.

-8.jpg)