The man-child is a staple of movies. Mostly dim-witted, often simply endearingly immature, he is the go-to character when regular films want to explore untrammeled honesty in the face of a cynical world or when comedy films want to explore just plain silliness. Unfortunately, most of these efforts are maudlin at best, saccharine or asinine at worst. So expanding the form to feature a woman-child is a risky proposition, and one that would likely be doomed to an even more sappy-headed failure once the suits and bean counters held sway over the rewrites. Well, to those with the power to green-light projects, don't stress. The definitive woman-child movie has already been made. It was in Italy, it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, and it was in 1957, long before Hollywood stopped making serious drama.

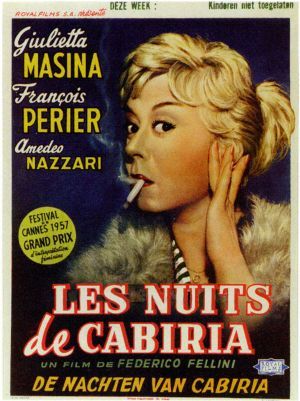

Nights of Cabiria (Le Notti di Cabiria), directed by Federico Fellini and starring his wife Giulietta Masina (she died in 1994, mere months after her husband), subverts, humanizes and then subverts again the screen convention of the whore with the heart of gold. Playing off a script by Fellini, Ennio Flaiano and Tullio Pinelli, Masina plays Cabiria as a woman-child who is resolute about taking as much joy as she can from life despite the fact that working as a prostitute from a very young age has, make no mistake, beaten her down. She chooses to summon that joy not because she is a simpleton, but because she is made of such stuff that she can see no other way. So Masina invests her character with an innocence and openness that is both inspiring and heartbreaking (see, it's the 'heartbreak' most movies don't get right, because with stories about plucky unfortunates they are too busy putting all their eggs into the 'inspiring' basket). Masina is astonishing in this role, utilizing a tightly controlled yet graceful physicality combined with one of the most expressive faces in the history of film. She is, without a shred of hyperbole intended, a near-reincarnation of Charlie Chaplin, and she can convey equally as much inner longing without words as the Little Tramp could.

When we meet Maria 'Cabiria' Ceccarelli, she is drowning; having fallen into a river after a shiftless new boyfriend steals her purse. She is surly and hardly seems grateful when some local townspeople fish her out and save her, but it is only because she is ashamed at what she allowed to happen. She returns to her small stucco home in an arid, desolate part of the Rome suburbs where her bad mood continues, ticking off her neighbor and dear friend, fellow streetwalker Wanda (the voluptuous and memorable Franca Marzi). Long the subject of ridicule among her peers, Cabiria endures criticism for her naïveté from all the ladies of the night that patrol the same town square in Rome. So when happenstance finds her being picked up by a famous movie star (Amedeo Nazzari) she is eager to prove to her cohorts that she has a more exciting life than they think. But, in another in a string of disappointments, Cabiria is only a distraction for the actor, who makes her spend the night in the bathroom with a beagle puppy, while he has make up sex with the volatile, gorgeous socialite he spurned earlier. So much for big dreams. Soon after, in the film's glorious set piece, Cabiria and her sinful compatriots make a pilgrimage to a sacred mountain, where throngs of the sick and troubled come to pray to an effigy of the Madonna. Miffed that a petition to the heavens does not yield an immediate change in circumstances, Cabiria storms off. She wanders into a cabaret show where is persuaded to come on stage and submit to hypnosis. Under the magician's spell, she speaks of her youth, and of her need for true love, devastated (but not dropping her tough exterior) when she comes out of it and realizes she is being mocked by the rowdy audience. Only the kindly Oscar D'onofrio (François Perier) seeks her out afterwards, and begins a tentative and tender friendship with her. Their affection for each other grows, and Maria's heart is once again big, wide and open. She is ready to change her life, and we are ready with her, but cannot help be frightened for her fate.

Fellini directs with a combination of documentary and magical realism, never letting us know for sure what life holds in store for Cabiria or, indeed, for anyone. We get the sense of someone behind the camera who despairs for humanity, but who has created a channel through which he can always find hope. And Giulietta Masina is that channel, plain and simple. She occupies, lives in, owns every frame of this film. Some grand black and white cinematography by Aldo Tonti is there to complement her presence, as is the expressive recurring musical theme by the one and only Nino Rota. Simple, unadorned and truthful, this is Fellini at his most commanding and profound. It is impossible to forget both Cabiria and the film that bears her name.

James Napoli is an author, filmmaker and teacher whose third book Violation! The Ultimate Ticket Book will be released in April.

.jpg)