David Ichioka is well-versed in off-kilter animation, with experience ranging from Gumby Adventures and Bump in the Night, to The PJs and Happy Tree Friends. His latest effort in the world of stop-motion animation is as a producer on Laika's latest feature, The Boxtrolls. Ichioka was kind enough to give us a presentation on the upcoming film that covered the nuts and bolts of the animation process and also gave us a more personal peek into the world of a stop-motion animator.

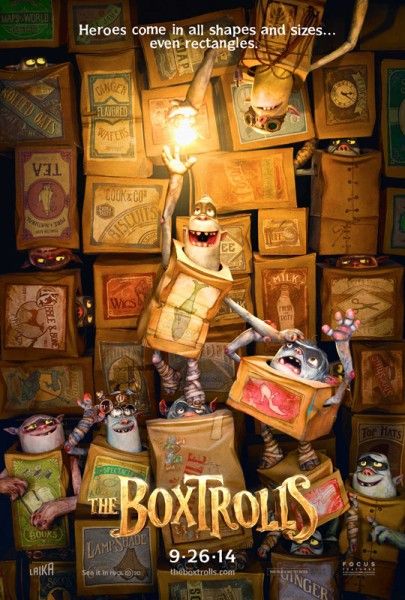

While on set of The Boxtrolls, Ichioka talked about the film's setting and what made Laika's style of stop-motion animation a perfect fit for its look, the decision to make The Boxtrolls a hybrid film by including motion-capture and visual effects work, and the evolution of stop-motion technology. In addition to providing us with a jaw-dropping list of numbers related to the picture, he also commented on the film's excellent voice cast, and the unique qualities of Laika's CEO and lead animator, Travis Knight. Hit the jump to see what he had to say, and be sure to check out The Boxtrolls when it opens September 26th.

David Ichioka: [The story is set in an] English, London-esque town. It’s not exactly that, it has sort of a steampunky sensibility in that it’s very anachronistic in its technology. So we have this sort of Victorian or Edwardian surroundings, but there’s electric lighting. And these little trolls, who live in discarded cardboard boxes instead of wearing clothes, also have power generators and strings of lightbulbs in their caves. We never met an anachronism we didn’t like, because after all, what is stop-motion but an anachronism and a contradiction in and of itself? Just even the words stop and motion together to describe something shows that we’re hopelessly conflicted people here at Laika.

So that was, once upon a time, one of the conflicts that people in stop-motion really had, was how to deal with visual effects inside of the picture, but we have thrown off those childish things and we now have these two things living together in harmony. What we use our visual effects for are to make up for what have typically been compromises that people in stop-motion community make, and one of those is, as you know, our approach toward facial animation, which involves computers very extensively, but also in the case of Boxtrolls, it’s much more about not having our film feel claustrophobic. It’s feeling open and wide, a big world with big buildings and long vistas; we’ve opened up our world and we’ve populated it, which are two things that … “cast of thousands” is not one of those things that stop-motion producers tend to smile about when they see it in the script. It’s right up there with “oceans of water” and things like that. But we haven’t shied away from any of those things on Boxtrolls, and we’ve pushed the facial animation using the computers and the 3D printers farther than we’ve ever pushed it.

On Coraline, you saw a little bit of the 3D printing that was used. It’s called replacement animation. Stop-motion animation is basically the art of making fabulous little tableaus, photographing them one at a time, and then when they run at 24-frames-per-second, they appear to move and the characters appear to live inside of them. That can either be done by taking something that is flexible and adjusting it every time you make one of these tableaus and shoot a new frame, or you can do what’s called replacement animation which is removing something and putting something back in to take its place, which is slightly different. That’s how we approach most of our facial animation. We don’t go in there and slightly adjust, we take it out and put in something that has been adjusted beforehand and replace it as the face is replaced. And then when it runs at 24 FPS it looks like one face that is moving around and emoting and acting.

On Coraline, we were able to do this to a limited extent. One of the biggest advances that we’ve made since then has been that now we’re able to do it in full-color, whereas before on Coraline we hand painted those faces. So we got like six freckles that we had to be very careful and moved about in a way which made sense. Now we have painterly multi-colored faces with all kinds of detail on them that all moves about on the face in a way that, hopefully when you look at it, makes sense, and doesn’t look like, “What’s that random motion going on in the face?” which is the bugaboo of all animation, things that don’t animate, which means they just sort of move randomly; they’re noise and what we want is signal.

I wanted to give you a few numbers before we got started because everybody wants to know these numbers. One is our headcount, our crew on the show, has been about 330 people. That’s not counting people working at other facilities, that’s not counting sound engineers or our voice actors, just people working here. Of those 330, 30 of those people, at the most, were animators. So people who actually do the shots, make the characters act, made final shots, were outnumbered more than 10 to 1 by people supporting them, creating sets and props, faces sometimes, doing storyboards, doing all the other things that have to be done to make one of these films. Producers, every once in a while. We had a production period of 72 weeks on Boxtrolls. We started with two animators but ramped up to that maximum of 30, which interestingly enough, we only hit 30 for about a month during that whole thing before we started tapering down again. But if you were to draw a curve of what our ramp up and ramp down looks like, it’s not much of a ramp down.

We’re building this up. We’d love to start with all 30, but you never can, and it’s not because you can’t find those 30 people, even though that’s part of it. You can’t because, at that point, you’re still furiously building sets and puppets and duplicates of puppets, you just don’t have things to animate with until really like eight or nine months into the project, the production of the project. So 72 weeks of shooting, during which time each those 30 animators are responsible for four seconds of animation a week. So a little less than 20 frames a day on average. And that doesn’t specifically mean they’re doing 20 frames a day, because they’re shooting rehearsals and blocks and things like that as well. Not everything they do every day that they’re out there is shooting production, but it isn’t that far away from that, oddly enough.

The film is 87 minutes long, which is 125,280 frames. And on every single one of those frames, somebody has touched it and changed it. And in the case of what we’re doing here, we’re so clever with our compositing techniques and such that we make our work even harder for us, because there’s quite often more than one frame of animation that goes into the final frame of the film. We’ll shoot something on the stage with more actors or different actions going on and composite those things together, so in fact our animators … even though our movie is 125,280 frames long, we actually shot more than that many frames. So our cutting ratio is in the negatives.

Our voice cast. We have pretty much headlining as the main villain, Archibald Penelope Snatcher is Ben Kingsley, who as far as I know, this is his first major animated film, and I don’t think it will be his last. He really has a fantastic animation voice. There aren’t that many great, great animation voices out there, but I think he qualifies. His band of misfits, The Men in Red Hats, his stooges, are made up of Nick Frost, Tracy Morgan, and Richard Ayoade. Richard, not a household name in the United States; we sort of went a tiny bit out on the limb by hiring somebody who’s more of a household name in the UK, but I do believe he’s another one of those great animation voices. I think doing animation after this point will help support his directorial career, which is already going great guns, I guess. The lead of the film is played by Isaac Hempstead Wright, better known as Bran from Game of Thrones. His associate, compatriot, whatever, is Elle Fanning, who plays Winnie, the female lead. Winnie Portley Rind, who is the daughter of the hoitiest, toitiest, most-powerful man in town, played by Jared Harris, as Lord Portley Rind, and his wife Lady Portley Rind, played by Toni Collette. On top of all this, we have Simon Pegg playing Herbert Tropshaw, The Man in the Iron Socks. Interestingly enough, Simon and Nick didn’t realize that each other were playing in this movie until half-way through their tenure on it, which was interesting because you imagine those two being joined at the hip and in fact they are very, very close friends, but they just don’t talk about projects that they’re on that the other one isn’t on, because they’re so polite. They’re both lovely gentlemen.

You’re going to be meeting with Travis Knight, who is my boss, another producer on the film, the CEO of Laika, and our lead animator, and has probably done more seconds of animation on this film than any other animator, interestingly enough. Quite a force of nature. Very unusual that a CEO would also be out on stage in the dark, pushing puppets around, wrecking his back and his hands half the time, but I think that it speaks volumes. A lot of other studios can say they’re in the business because they love it, but I think Laika has got real evidence. That’s a big part of why we do what we do, and I think it shows in what we do.