The riots changed everything. On June 28, 1969, customers of the Stonewall Inn, a popular New York City gay bar in Greenwich Village, had finally had enough when police attempted to raid the bar and arrest its patrons. Customers fought back, and a three-day uprising against law enforcement's treatment of the city's gay residents brought the community out of the closets and into the streets once and for all. The "gay liberation" movement, as it was called 54 years ago, was now open, proud, and retreat-proof. A year before the Stonewall riots, a young playwright (and personal assistant to actress Natalie Wood) named Mart Crowley brought to the off-Broadway stage his story about a group of Manhattan gay men getting together to celebrate a friend's birthday. The Boys in the Band was the first successful American stage production in which all the featured characters were gay. The play ran for nearly two years and was attended by an audience of diverse luminaries like Jackie Kennedy, Groucho Marx, and Marlene Dietrich. With the success of the production, and with the increased visibility of the gay community following Stonewall, Hollywood took note and took a chance, bringing the story to the big screen in 1970.

Never before had a mainstream studio, National General Pictures, which had released Scrooge and Little Big Man that same year, brought to the big screen a story about a night in the life of eight gay men (and one questionably straight man). Never before had a successful mainstream director (William Friedkin) been enlisted to helm such a controversial project. Even more daring was the fact that six of the film's actors were gay themselves. The film's promotional poster was bold for its time, as well, featuring a picture of two men, one in sunglasses with a cigarette hanging from his mouth and accompanied by the caption, "Today is Harold's birthday," and the other a handsome young blonde with the words under his photo reading, "This is his present." The movie was celebrated as a groundbreaking achievement in queer cinema and a giant step forward in recognition of the gay community. While there's no doubt that The Boys in the Band was a landmark in both modern movie history and queer history, looking back at it nearly 53 years following its release, the film's sad tone and dark themes raise the question of whether the movie is more harmful than helpful to the gay experience.

A Story of Gay Life Before Stonewall

It's important to keep in mind that Mart Crowley wrote The Boys in the Band in 1968, a year before the events that spawned the modern gay rights movement, and the film also takes place in 1968. The gay community was still largely closeted then, there were laws on the books that criminalized homosexuality, and gay men and lesbians were regularly subjected to discrimination, harassment, and violence with no legal protections. There's no mention of gay liberation or any other social or political issues in the film (save for one extremely uncomfortable racist joke). The movie's characters all live in an insular world, out to only their small circle of friends, but otherwise blending into the heterosexual community. The major exception is the character of Emory (played by All That Jazz's Cliff Gorman, one of only three of the film's actual straight cast members), who might be described as someone so flamingly gay, he could set off fire alarms.

In the movie's opening sequence, Emory is seen mincing down 5th Avenue with an exaggerated flourish, his fluffy white toy poodle on a leash, glancing at all the young male hustlers he passes on his way home from his job as an interior designer. On the one hand, Emory is a character well ahead of his time - a man who wears his flamboyance proudly, who doesn't care what others think, and who isn't afraid to embrace his queerness. On the other hand, he's also a tired stereotype - a cringe-inducing trope of how straight people view gay people as light-in-the-loafers prancing fairies. Emory is a polarizing character, to be sure, and it's safe to say 1970 gay audiences probably squirmed in their seats a bit when they saw Emory burst onto the screen.

Alan Represents 1968's Homophobic Culture

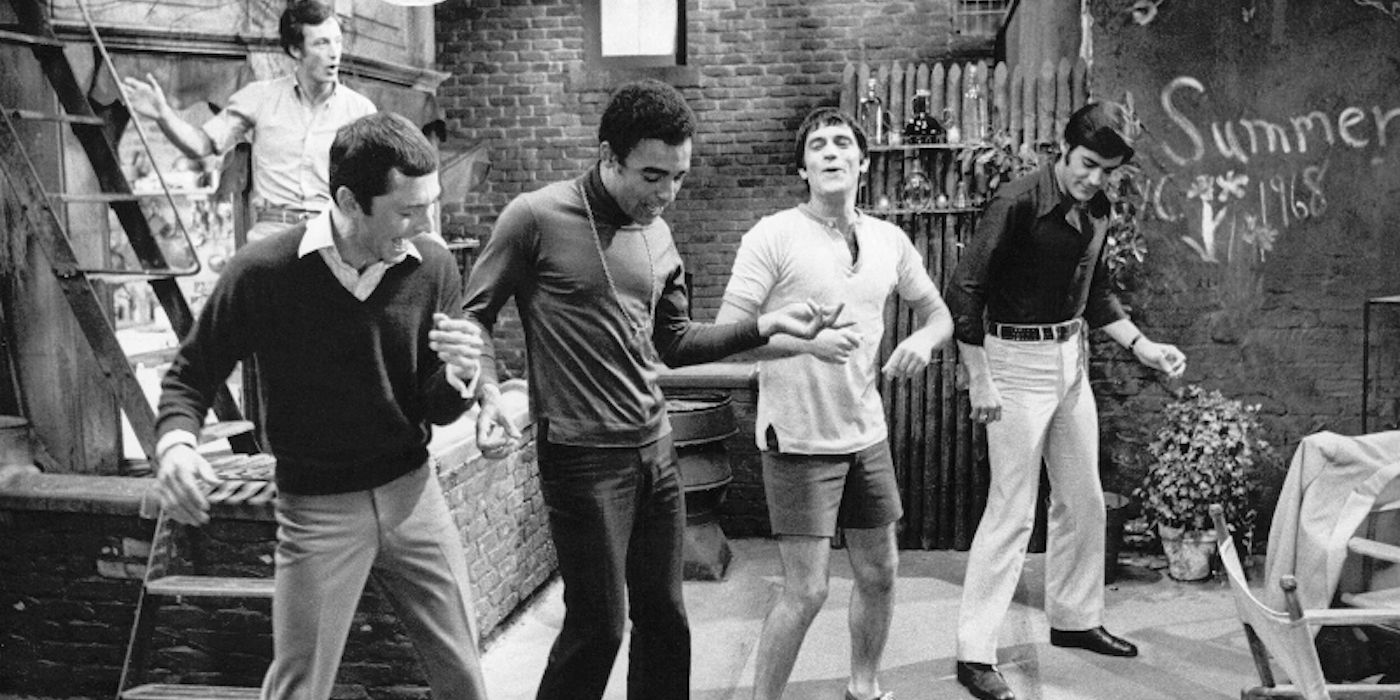

The film's premise is simple - seven friends gather to celebrate a birthday. Emory has even hired a street hustler as a gift for the birthday boy, a handsome young man (Robert La Tourneaux, in an underrated performance that's both comical and heartwarming) dressed as a cowboy and whose physical beauty makes up for what he lacks in brains. All seems to go well until the host's straight friend from college shows up unexpectedly and crashes the party, which unleashes a Pandora's Box of homophobia, hatred, and cruelty among the guests. Director Friedkin's direction is outstanding, and the way he shifts the movie's locations to match the shift in tone is genius. As the film begins, the friends gather on host Michael's (Kenneth Nelson) outdoor apartment terrace. The mood is jovial, with the buddies trading catty barbs and dancing to Martha and the Vandellas' "Heat Wave" as they await their terminally tardy guest of honor Harold (Leonard Frey in his Golden Globe-nominated performance).

When Michael's straight Georgetown acquaintance Alan (Peter White) arrives, things quickly get uncomfortable, and that's when Friedkin moves all the characters to the inside of Michael's claustrophobic feeling living room. What began as a seemingly joyful celebration of gay abandon and openness becomes a closed, murky exploration of the human spirit's darkness. Alan is put off by Emory's unapologetic peacockishness, describing Emory as "a butterfly in heat," which leads to a physical altercation between the two men. Screenwriter Crowley uses the character of Alan as a representative of 1968 heterosexual culture, threatened by what it sees as the brazen flaunting of the gay lifestyle that needs to be shamed back into the closet. Once the fisticuffs start flying, the guests at Michael's party are no longer free to be themselves. They retreat, hang their heads, and shut down, relinquishing their power to Alan, the lone heterosexual in the room.

A Sadistic Game and Tormenting Queer Characters

Meanwhile, the once clean and sober Michael jumps off the wagon and starts drinking, transforming from a congenial "hostess with the mostest" into a hateful beast, brimming with contempt and loathing for everyone around him. This is where the film becomes especially distressing to watch. The movie's characters are no longer content, proud gay men. They are, instead, despondent, spiritually flogged, and emotionally castigated. Things continue to devolve when birthday boy Harold (described by himself as "a 32-year-old ugly, pockmarked Jew fairy") finally arrives. Harold is whip-smart, caustic, hilariously acidic, and intolerant of Michael's bullying behavior. "We tread very softly with each other," Harold calmly daunts Michael. "I know this game you're playing. I know it very well, and I play it very well...I'm the only one who's better at it than you are."

Michael is nonetheless undeterred by Harold's snide commentary and decides to engage in a sadistic parlor game in which his friends must pick up the phone, call the one person in their lives for whom they've always pined, and tell them that they love them. Of course, two of the men confess they've long carried torches for specific straight men in their lives, perpetuating the unfortunate myth that gay men can't ever truly feel fulfilled, because they'll never get the heterosexual guy of their dreams. Emory's story about his unrequited love for a boy he longed for since grade school is agonizing and poignant, yet Michael doesn't let him off the hook, berating Emory, taunting him with the question, "Who would go to bed with a flaming little sissy like you? Who'd make a pass at you? I'll tell you who - nobody. Except some fugitive from the Braille Institute."

While Crowley's objective may have been to get to the raw truth about the film's characters, this scene comes off as unnecessarily torturous and cruel. When Michael turns his fury to heterosexual Alan, accusing him of having had a clandestine affair with a male classmate during college and daring Alan to call that classmate on the phone, Alan doesn't fall for it and dials his wife instead, telling her he loves her and that he's coming home. While it's never made clear whether Alan is a closeted homosexual himself, the film's message is unmistakable. Alan has what Michael doesn't - a wife and a family, and even if Alan may really be gay deep down inside, he's still better off than Michael, because he has someone to go home to. Harold further drives that message like a stake through the heart in his fiercely painful final takedown of Michael. "You're a sad and pathetic man," Harold tells Michael. "You're a homosexual and you don't want to be. But there's nothing you can do to change it. You'll always be a homosexual. Always. Until the day you die."

A Harmful Message of Self-Loathing

As the defeated guests leave the party, Michael suffers a long-suppressed emotional breakdown, falling into the arms of his one true champion, best friend Donald (Frederick Combs), and offering what is perhaps the smallest glimmer of hope in this otherwise downbeat experience. "If we could just not hate ourselves so much. That's it, you know. If we could just learn not to hate ourselves quite so very much." But after nearly 90 minutes of psychological and spiritual torment, this sentiment feels a bit like pouring water on a house that long ago burned to the ground and is now nothing but a mountain of smoldering black ash. How did gay audiences react to the film's bleak themes at the time? It's hard to imagine that they felt empowered by a movie that told them they were really nothing more than self-loathing individuals who longed to be anyone but who they really were. Yes, the film was revolutionary in that it brought queer cinematic representation to the forefront, but at what price? How many gay men may have watched the movie, then walked out into the cold streets feeling even more alone, unloved, "less than," and without hope? Was the visibility worth it, or did it simply amplify all the same negative, grim images so unfairly engrained into the queer person's psyche for so long? Adding an even more somber coda to it all is the almost unthinkable realization that five of the film's cast members succumbed to AIDS between 1986 and 1993.

The 2020 Remake's Tone Remains Bleak

In 2020, producer Ryan Murphy teamed with playwright Crowley to bring a new version of The Boys in the Band to Netflix, featuring a cast that included Jim Parsons as Michael and Zachary Quinto as Harold. Directed by Joe Mantello (from Murphy's The Watcher and American Horror Story: NYC), the updated story is completely faithful to the original, and in some ways, more dreary than the first, with Parsons as an even more contemptible party host. Perhaps Murphy and Crowley wanted to preserve the tone of the original stage play and film as a sort of time capsule - a reminder of the gay experience five decades ago that should serve as an appreciation for how far the community has come today, even against horrific odds like a deadly health catastrophe that ravaged far too many of its members. Yes, The Boys in the Band should be acknowledged as a trailblazing part of queer film history, but maybe it should also be acknowledged as a sad reflection of the gay experience that has thankfully retreated into the past and should remain there.