The “soft reboot” or “legacy sequel” has become Hollywood’s most popular way of relaunching an established franchise under the guise of being a sequel, yet still retaining the original film’s characters in a supporting role. At their best, legacy sequels can introduce a new generation of heroes and pass the torch earnestly, as epitomized by films like Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Creed, and Blade Runner 2049. At their worst, films like Jurassic World, Independence Day: Resurgence, and Terminator: Genisys shamelessly pander to nostalgia and rely on familiar iconography without narrative functionality.

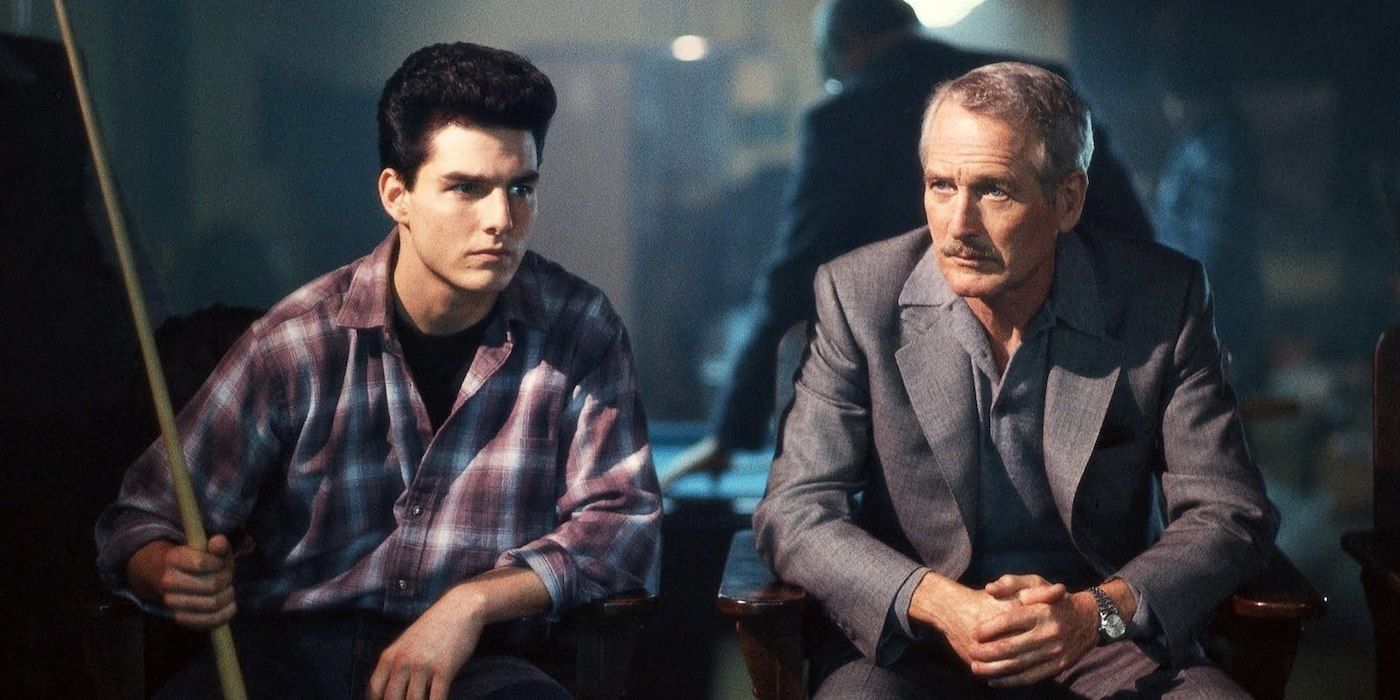

It's likely this trend will only continue, but it's hardly a recent invention. Legacy sequels have existed for decades, and Martin Scorsese’s 1986 gambling thriller The Color of Money is one of the earliest examples. The sequel to The Hustler came 25 years after the Oscar-winning original, and picked up with the further adventures of the hustler “Fast Eddie” Felson (Paul Newman, in the role that finally earned him the Academy Award that eluded him throughout his career). Fast Eddie is on another cross country adventure headed towards a major pool tournament, but this time he’s mentoring the up-and-coming nine-ball champ Vincent Lauria (Tom Cruise).

The plot is nearly identical to The Hustler, and wrestles with the same theme of the ultimate emptiness of gambling culture. There are many callbacks to The Hustler, as Fast Eddie knowingly walks Vincent through the same scenarios he experienced at the same age. Despite the overt similarities, The Color of Money is a great film in its own right, and the differences it does have with The Hustler distinguish it so that viewing the original isn’t even a requirement. It's an example of a legacy sequel done right.

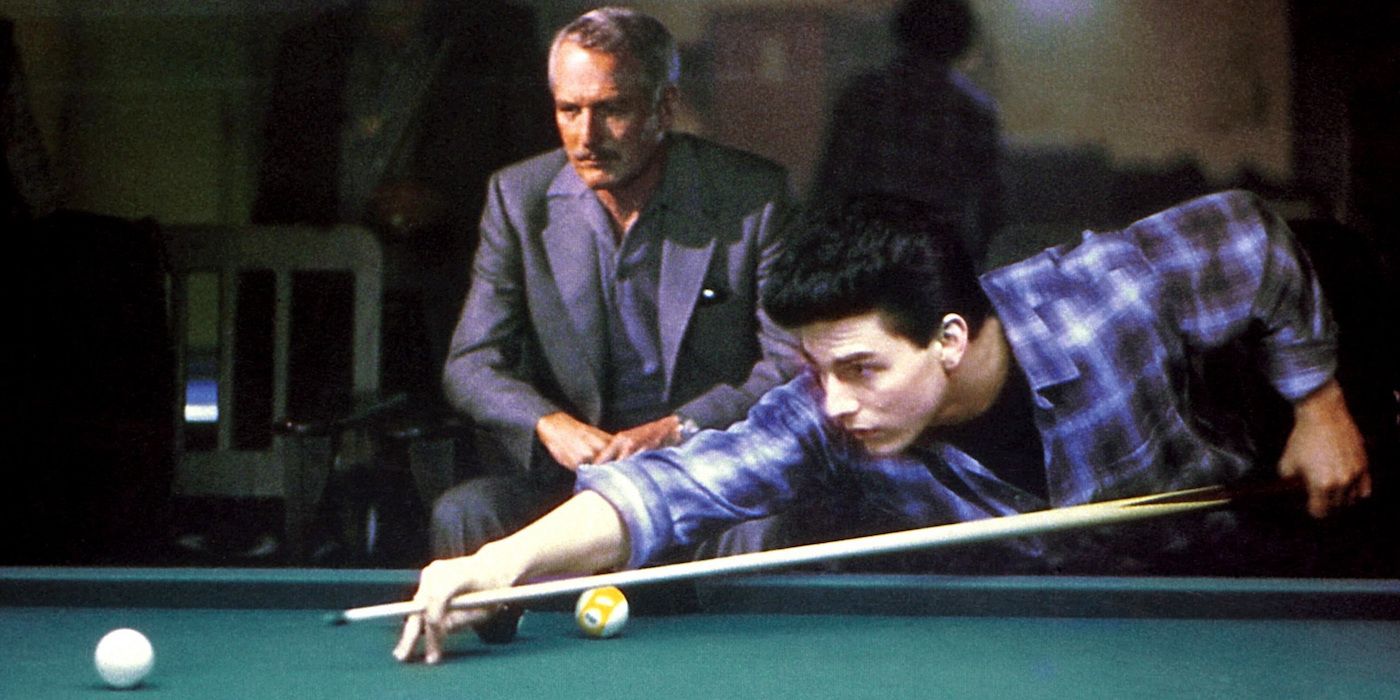

Although the story is a beat-for-beat reimagining, the tone and style are radically different. Robert Rossen’s 1961 original was acclaimed for its grittiness, and focused on the most sordid details of Fast Eddie’s addictive personality. While he’s renowned for his dark and even nihilistic style, Scorsese adds a propulsive pace and crafts a work of pop entertainment. The gambling scenes that were methodical and prolonged in The Hustler are now instilled with the same kinetic energy of the montage sequences of Goodfellas or The Wolf of Wall Street.

The change of energy largely stems from the main character, as while Vincent follows in Fast Eddie’s footsteps, they’re two completely different people. When he’s introduced in The Hustler, Fast Eddie has already been beaten down by his lifestyle and made personal sacrifices in order to justify his behavior. Vincent still revels in each victory and enjoys goading veteran players with his youthful overconfidence. Coming straight off of the success of Risky Business and the same year as Top Gun, it was Cruise at his most charismatic.

Legacy sequels often succeed or fail based on how successfully they incorporate the original stars. Creed was as effective as it was because it gave Rocky (Sylvester Stallone) an emotional throughline of his own as he contemplates the consequences that he fears Adonis (franchise newcomer Michael B. Jordan) will face, whereas something like Independence Day: Resurgence trods out Bill Pullman because Bill Pullman was in the original. The Color of Money is just as much Fast Eddie’s story as it is Vincent’s; he sees the young man’s potential and decides to capitalize on it, finding himself drawn back into a profession he knows has only been a burden to him.

Fast Eddie is older and perhaps a little wiser, but he’s tragically faced with the same hardships he did in his youth. He tries to mask his own loneliness with a winking charisma, and it's clear why Newman’s subtle performance won him the Oscar (and why it's far from just the “career win” some may claim it is). Fast Eddie is actually challenged by Vincent and forced to question his own intentions. Can he live with himself if he dooms Vincent to the same downward spiral he knows all too well, or is this new hotshot destined to prevail when he couldn’t?

As Fast Eddie is conning Vincent, he’s not framed in a traditional “mentor” role where he’s repeating his old phrases for nostalgic purposes. The callbacks that do come are mostly through dialogue (Fast Eddie notes Vincent’s “natural character,” as an example) and don’t have major ramifications on the story. Despite having a major role in the original novel, Jackie Gleason’s Minnesota Fats doesn’t show up because there wouldn’t be a narrative purpose for him and his arc has already been concluded. By avoiding any cheap pulls at familiarity, the references The Color of Money does make are more rewarding.

At the same time, someone who hasn’t seen The Hustler wouldn’t be confused, as the chemistry between Newman and Cruise is entertaining in its own right. The Color of Money takes the core concept of the original and tells a new adventure, and doesn’t try to bury it in pointless mythology. It does what every legacy sequel should try to do — introduce the world to a new generation while rewarding older fans with an authentic depiction of their favorite characters.

Repetition makes sense within the world of The Hustler and The Color of Money. Twenty-five years later, a gambler doesn’t simply forget the mistakes he used to make, and it makes logical sense that Fast Eddie would wind up in a familiar setting. There’s no shame in nostalgia, but it can’t be the only asset a film has. This classic example of a legacy sequel remains one of the best, and sets a template today’s blockbusters should strive for.