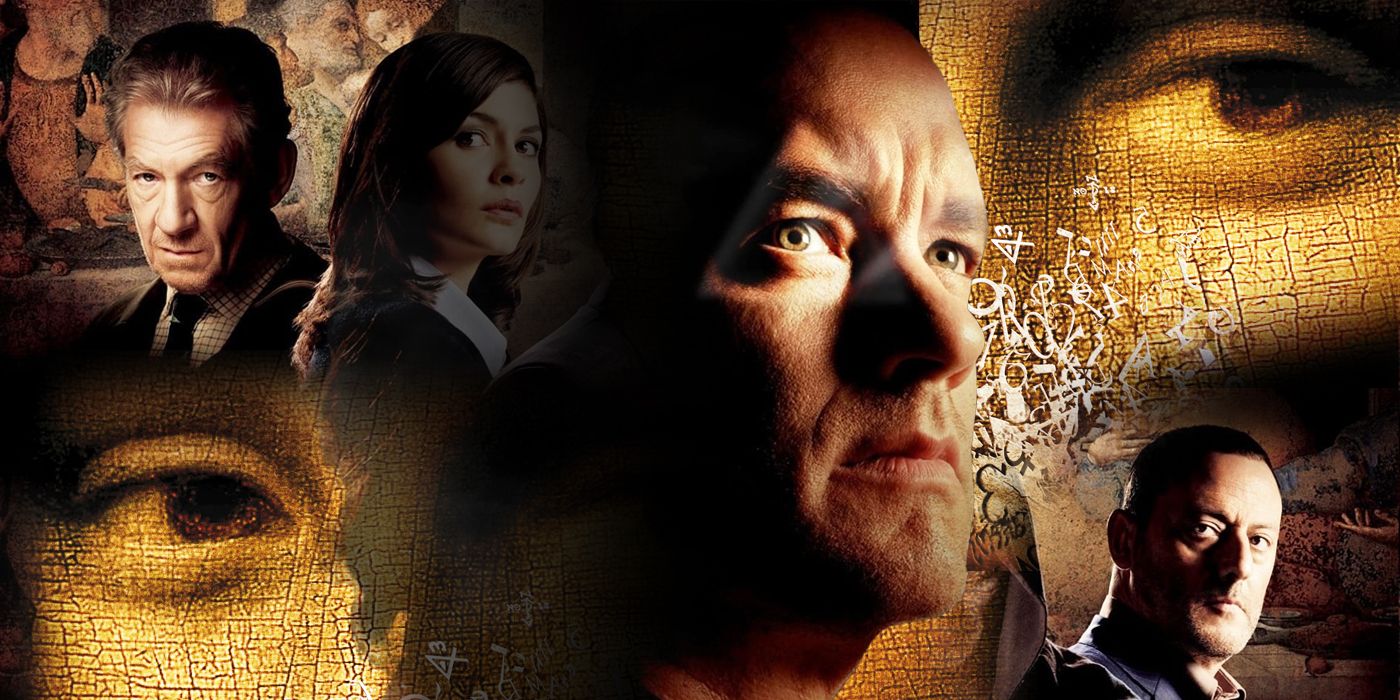

In 2003, The Da Vinci Code ruled the world. It may have received a critical drubbing so bloodthirsty that the world’s literature publications briefly turned into slaughterhouses, but as numerous commercial sensations have proven, bad reviews need never be an obstacle between an artist and international fame. Dan Brown might not win a Pulitzer, but there is something commendable about his talent for crafting a fast-paced thriller where every action dictates the fate of humanity… if only he didn’t follow it up with prose so clumsy it reads like a guide on how not to construct a sentence. Still, anything that takes highbrow subjects and repackages them into a digestible page-turner is primed to do well, and that’s exactly what happened. Practically overnight, The Da Vinci Code became one of the bestselling books ever – an accolade it solidified three years later when its Ron Howard-directed adaptation came along, the first in the Robert Langdon trilogy starring everyone’s favorite Tom Hanks. Together they rejuvenated discourse on the Holy Grail and the history of Christianity, ushering in a new age of homegrown scholars ready to decipher centuries of religious text. If only their newfound interest wasn’t based on lies.

“All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate”, as the opening page of The Da Vinci Code proudly announces – a bold statement for a novel that is entrenched in a fantastical version of history. The simple truth is that most of The Da Vinci Code is based on historical and religious inaccuracies, and while such criticisms are usually dismissed under artistic license, Brown’s insistence that his novel is “99% accurate” makes them harder to justify. How intentional these mistakes are is contentious, especially after his subsequent books continued this pseudohistory approach in a thinly veiled attempt to recreate The Da Vinci Code. But as the saying goes, don’t fix what’s not broken (or alternatively, don’t change what’s bringing in the money). The willingness of its Hollywood counterpart to ditch this truthful façade in favor of good old-fashioned escapism was its greatest improvement on the source material, but those falsehoods that had previously sparked global protests remain untouched. Here are the most egregious examples.

Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene Were a Couple?

The most controversial element of The Da Vinci Code is its claim that Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene were married, with Mary also being pregnant at the time of Jesus’s crucifixion. Their bloodline (and by extension, Mary’s womb) is the Holy Grail, and protecting this secret from those wishing to remove it from history is the Priory of Sion’s primary goal (one of the many secret societies Brown throws around like confetti). This revelation comes to us via Langdon’s friend Sir Leigh Teabing (Ian McKellen) during one of the film’s innumerable exposition dumps, with the brunt of it being that it would undermine the Church’s credibility should it become public knowledge. It’s an assertion that Teabing (and by extension Brown) makes with supreme confidence, and is rather cocky of him given that it uproots the entire foundations of Christianity. But as those involved with the protests against The Da Vinci Code (which included the film being banned in several countries) will affirm, it’s a claim with no historical basis.

For starters, the idea that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married has been a contentious one long before Dan Brown entered the scene. While there is no disputing Mary’s significance in the Bible, she is mentioned by name twelve times across the four canonical New Testament gospels, which is more than most of the Disciples. None refer to a relationship between her and Jesus, with the focus kept predominantly on her discovery of Jesus’s empty tomb on Easter Sunday and his appearance to her following his resurrection. The notion of her being more than a simple follower comes from the non-canonical Gnostic Gospels, discovered in Southern Egypt in 1945. These texts present them in a closer relationship, with the Gospel of Philip describing her as Jesus’s companion, something Teabing uses to reinforce his belief given its translation from Aramaic to English to mean “wife” (which is an odd thing to bring up considering it was written it Coptic). It’s worth noting that these gospels were written long after the historical Mary Magdalene had died, making them poor sources to ascertain her character. Given their importance to Teabing’s majestic conspiracy theory, already he’s off to a poor start.

The Da Vinci Code also makes other erroneous claims about Mary Magdalene. There’s no evidence that she hailed from the Tribe of Benjamin, thus making her and her descendants royalty with her surname which translates to “from Magdala”, an ancient city in northern Israel, suggesting quite the opposite. Similarly, you’d have to search far and wide to find a respected art critic who supports the theory that Leonardo da Vinci sneakily inserted Mary into his famous The Last Supper painting. The feminine portrayal of the apostle John is perfectly in keeping with Leonardo’s established style, and Mary’s ventured status would have negated having to hide her insertion anyway. On the flip side, Brown does correctly debunk the misnomer of Mary being a prostitute that originated from a sermon in 591 by Pope Gregory the Great, lending his theories some credibility.

It’s No Secret, Those Secret Societies Are Fake

But the inaccuracies of The Da Vinci Code extend beyond just Mary Magdalene. For example, the aforementioned Priory of Sion – which Brown claims on the novel’s opening page is a real organization from 1099 whose members include Isaac Newton and Victor Hugo – is actually a hoax created in 1956 by Pierre Plantard whilst trying to steal the crown of France. There’s no evidence of the society existing before this date, and a 1993 police raid on Plantard’s home unearthed irrefutable proof that it was just a local pressure group that grew out of control… not exactly the stuff of a millennium-old society. Curiously, his prank was cooperated three decades later by the authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, a pseudohistorical book whose central hypothesis is borderline identical to the one found in The Da Vinci Code. No wonder two of its authors tried to sue Brown for copyright infringement.

Another society that Brown makes liberal (and slightly more accurate) references to is Opus Dei. Unlike the Priory of Sion, Opus Dei is an actual organization that exists as a subsect of the Catholic Church, although Brown’s depiction of it as a bloodthirsty cult waging a centuries-long war against a fabled secret society is obviously wrong. The Da Vinci Code introduces us to this organization via the albino and self-flagellating monk Silas (Paul Bettany), but this also displays many inaccuracies. Opus Dei does not contain any monks, and while some members pledge to remain celibate and exercise ritualistic self-harm, most choose to live a normal life that lacks such grand theatrics. With that being said, the practices of Opus Dei have ensured that it is far from controversy-free, making Brown’s exploration of it one of the few times that The Da Vinci Code comes within touching distance of reality.

'The Da Vinci Code' Tries to Mess with Roman History

And then there’s The Da Vinci Code’s other provocative claim that it was Constantine – the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity – who was responsible for the canonical form of the New Testament. If we take Teabing’s word for it, Constantine manipulated the Council of Nicaea in 325 to remove all gospels that referred to Jesus as a human prophet, leaving only the four gospels that portrayed him as divine (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). In reality, Jesus was considered a divine figure as early as the first century, with the council's main focus instead being on settling a debate started by the Alexandrian priest Arius about whether Jesus was inferior to God since he was born (thereby having a clear beginning). The argument wasn't based on if Jesus was divine or not, but rather if his divinity was equal to or less than his father's, a crucial distinction that Brown leaves out. Discussions related to the Gnostic Gospels (which, contrary to Teabing's proclamation, depict Jesus as an even more divine figure) did not take place, and the vote count was also unanimously against Aruis rather than it being a tightknit race as Teabing suggests.

But these are only a taste of The Da Vinci Code’s fractious relationship with the truth. Other smaller mistakes include Langdon’s claim that the Louvre Pyramid is made from 666 panes of glass (it’s actually 673), or that Paris was founded by the Merovingians (it was actually the Gauls). Such errors don’t matter in the wider scope of things, but one wonders why Brown wouldn’t correct such minor faults given the tone he’s trying to achieve. His theory that Leonardo da Vinci left clues about his secret religious beliefs throughout his extensive work as a painter – which no reputable theorist supports – is another example of this, although the narrative’s dependence on this would make it a harder fix. While we’re on the topic, even the title, The Da Vinci Code, is flawed given that Da Vinci was not his surname, but instead a reference to his father's hometown. Admittedly, The Da Vinci Code has a ring to it that The Leonardo Code does not, but it’s still an issue that makes the art world cringe (especially given that Robert Langdon, a supposed Harvard professor, is the prime culprit of this mistake).

Ultimately, 'The Da Vinci Code' Is Entertainment, Not History

In some ways, it feels strange to criticize The Da Vinci Code for its factual inaccuracies. Fargo, The Blair Witch Project, and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre all falsely present themselves as true stories, and all are held as brilliant works of cinema regardless. But none of those sought to undermine the basic pillars of humanity’s largest religion, one that plays an important role in the lives of billions. It was Brown’s willingness to dismiss the prevailing consensus on such matters (while repeatedly claiming that he was doing the opposite) that generated the pushback. However, the role The Da Vinci Code has since played in renewing public interest in Christianity (not to mention how it increased tourism to Paris and Rome) goes some in explaining why the backlash has diminished in recent years.

But ultimately, do these falsehoods matter? Brown writes entertainment, not history, and making your suspension of disbelief work overtime is half the fun of conspiracy fiction. The Da Vinci Code doesn’t blend fact and fiction as elegantly as All the President’s Men or as colorfully as Indiana Jones, but there is some catharsis in letting yourself be pulled into this make-believe world so ludicrous it makes Harry Potter look real. Nothing sells 80 million copies – or grosses $760 million at the global box office – without doing something right, no matter what critics say. Just don’t use Dan Brown as an excuse to skip history class. History can be an excellent source of entertainment, but remember that facts will always take a backseat in such adventures.