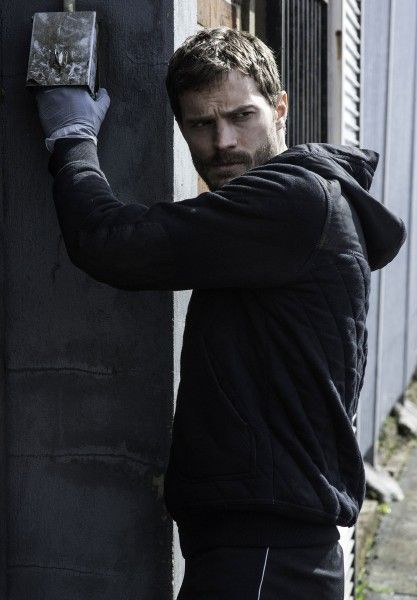

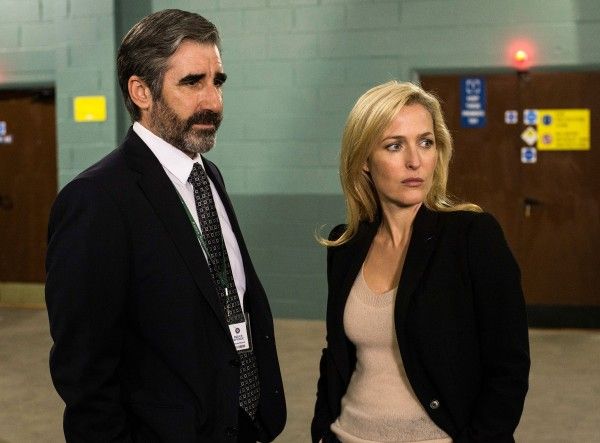

With Season 2 of the crime thriller The Fall available on Netflix, show stars Gillian Anderson and Jamie Dornan, along with creator Allan Cubitt, were on hand at the recent TCA Winter Press Tour. Set in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the story of the first season continues with Detective Superintendent Stella Gibson’s (Anderson) pursuit of serial killer Paul Spector (Dornan). The stakes are higher and the risks are greater, and the more Spector taunts and provokes Gibson, the closer she comes to capturing him.

During both the panel presentation and a 1-on-1 interview with Collider, show creator/writer/director/executive producer Allan Cubitt talked about where the idea for the series came from, the issues he was looking to explore, writing the role for Gillian Anderson, writing a charismatic and relatable serial killer, revealing the killer from the beginning, writing Season 1 without knowing whether there would be a Season 2, and that he does have an ending in mind, if he gets more episodes to continue this story. Be aware that there are some spoilers.

Collider: Where did the idea for The Fall start? Was there one thing that was the seed that started it off?

ALLAN CUBITT: Yeah, it came out of some reading and thinking I was doing about issues surrounding male violence. I’d been through the parenting thing with a daughter, of monitoring my protectiveness and my feelings of concern about where she might be and what she might be doing, and trying to gauge how far that protectiveness was rational and appropriate and how far it was patriarchal and inappropriate. The parenting of girls and boys is often very different, with the freedoms that we grant them and where the dangers are. I became concerned about what I saw as the eroticizing of young girls. There are the issues of the way in which they see themselves, the pornification of culture, and the way in which young girls feel as though they need to present themselves, if they’re insecure and doubtful about their place in the world, and how important it is to make people feel valued and loved and not judged. It’s the thing we struggled with as children, ourselves, and the thing we struggle with, as parents. All of those issues were playing around in my head. There is a speech from Gibson about the perpetual desire to broadcast your internal and external life, and photograph your food. All of this is alien to me because I’m old enough to have lived before any of that happened. The last thing you’d want to do with any of your friends was look at any of their photographs, particularly holiday photographs. It was a nightmare thought, if anyone would pull out an album or start a slideshow of their holidays. So, there’s this notion of what is private to us and what it means to have a private life, at all.

And then, if you’re entering into the territory of Spector, you’re dealing with a private life that is deeply disturbing and destructive, as well. You get into all of those issues about compartmentalizing and doubling, and so on. The idea that it could be a crime drama was just simply thinking about potential stories, and the way of telling stories. The very simple thing that occurred to me was that I’ve never been a very big fan of drama of revelation. The second thing I did for television was a drama of revelation, and it gets you into third act exposition. Things aren’t what they seem to be, and you build up to it, and then you’ve got this inevitable potential anti-climax. So, I just thought, “Would it be interesting and would it work, if you identified who it was that was doing the crimes from the beginning? Where would the dramatic tension come from?” It has worked. It does feel suspenseful, even though there’s no mystery about who’s perpetrating these crimes. You don’t really know what’s going to happen next, so in that sense, it works just like any other drama. If you make an investment in the characters, you want to know what they’re going to do next. I’ve always been interested in trying to draw characters that are individual enough not to react in the same way, in any given situation. My observation of the world is that we don’t react the same, in certain situations, and a lot of drama tends to perhaps have a generic reaction to things. I just wanted to get into the specifics of their psychology, really. So, the very simple idea was to identify him from the beginning, and look at what it is that he does and why he does it and whether it’s possible to stop him from doing it, and I wanted it to be complex for both sides of the equation.

Genre is not a difficult sell to broadcasters, for the most part. They don’t send you away for coming in to say, “It’s got a police dimension,” or “It’s got a hospital dimension,” or “It’s about a lawyer.” They feel slightly safer. It’s more difficult nowadays. If I went in and said, “It’s just about the break-up of a marriage,” they’d say, “What’s the unique selling point? Are they ghosts?” So, from that point of view, it was a really simple pitch. And then, we had to go away and work out exactly what would happen and how we could sustain a degree of dramatic tension and jeopardy. We have to keep the audience emotionally engaged in what’s going on, which is a challenge when one of your characters is such a horrendous individual. For that, you have to then be working on the basis that he is psychologically interesting, on some level. Otherwise, you won’t want to watch the show.

You wrote Stella Gibson with Gillian Anderson in mind, so what did you do to adapt it to her?

CUBITT: Well, the way it worked was that I always thought that Gillian would be the best person to play the part. I’d written three episodes of Season 1, and we approached Gillian and talked it through. And I was in the incredibly gratifying position of her saying that she was interested in doing it. It’s not very often that you get your first choice of actor, so that sets the project off in a really good way. I’ve done a lot of work over the years, and casting can scupper things completely, particularly if you’re in a position where you’ve got a green light and you’ve got to find someone to play a key role and the people you want are unavailable or don’t want to do it. Sometimes you find yourself compromising in a way that’s really bad for the project. So, having your first choice available to you is an incredible gift, in itself. What that meant was that I wrote episodes 4 and 5 of Season 1 with Gillian in mind, and then, of course, all of Season 2, knowing she was going to play it.

I’ve done it before. I wrote Prime Suspect, and then when Helen Mirren was suggesting she wasn’t going to do any more Prime Suspect, I wrote a four-hour piece with her in mind. I’ve had the experience of writing for actors. You hear their voice in your head and you try to play to their strengths, as an actor. You have a sense of what it is that they’re particularly good at. You can write an underwritten, concise, pay-it-back scene, knowing that you have an actor who is capable of imbuing it with all the emotion, the intelligence and the subtext that you want there. Writing for anyone who’s incredibly brilliant is a fantastic thing to be able to do. Otherwise, you’re writing scenes thinking, “I hope I can find someone who will be able to play this.”

How difficult was it to make Paul Spector someone who would still be charming and that audiences would want to watch, even with the horrible things he’s doing?

CUBITT: I did a lot of research. Obviously, there are people that are psychotic and mental, but the majority of the people who commit these crimes are not psychotic, at all. Disconcertingly, they come across as mentally quite normal, for some of the time. That is the baffling thing that we all look at and think, “How is that possible?” But, we do that in life. If you hear something damning and worrying about a person that you know quite well, then you find yourself looking at them with that sense that they’ve done that piece of behavior, or they have this interest or involvement in their lives. Even if someone has been revealed to be having an affair, you suddenly look at them completely differently because you have new information to try to factor in. So, I was really interested about how we get to know one another, on anything beyond a superficial level. What does it mean to be intimate with someone? How well do you really know the other person, and how well do you know yourself? The Fall deals with what I think are really fundamental, human questions, more than it is a police procedural drama.

Is the intention behind making a serial killer relatable to make viewers uneasy?

CUBITT: I think one of the reasons why The Fall has some of the impact that it seems to have is because it posits the notion that Spector is on a continuum of male behavior. He’s very much out there. It definitely suggests that there’s a continuity between all kinds of male behavior and what Spector is doing, so that he isn't a creation that’s got almost supernatural powers. He’s very much an ordinary man, and that is disconcerting for people. It was a deliberate choice to try and create a character that was closer to what I think is the reality of these situations, than some of things we’ve encountered before in film or in fiction.

Is Spector totally manipulating Katie, or does he see a kindred spirit in her?

CUBITT: I think it’s a complex dynamic between them. I find it interesting. Gibson questions him about the need to corrupt someone, in that way, and what on Earth he could be gaining from it. But Spector’s a character who is always looking to exercise his will and his power, in his attempts to control everything around him, and she falls into that territory. He clearly sees her as being useful. She’s someone that he feels can do his bidding. But, I was interested in the way in which a lot of these individuals who prey on other human beings are alert to vulnerability. They recognize something in people. There are children who are vulnerable to adults abusing them, and they are often conspicuously needy themselves. I think Gibson has an affinity with Katie. There’s the business of losing a father, at a particular point in your life, and being vulnerable and open.

So, her feelings are complex. She’s clearly flattered by his attention. She is perhaps in love with him, in some misguided kind of way. It’s a very new experience for her. She uses it to try to impress her cooler, sexier, more experienced friend. I think it’s quite typical teenage behavior, particularly if there’s some vulnerability there. But to use a cliche, she’s playing with fire and doesn’t perhaps quite realize it. I don’t think it’s completely clear to me whether she thinks that he is the hoaxer or the murderer. At the end of the second season, she’s facing a court case and possibly some proper punishment for her behavior. Hopefully, it’s quite complex.

You envisioned this as 12 hours, but you did the first season without knowing if you’d have a second season. When you were structuring this, did you ever think about trying to condense what you wanted to say with it, in case you didn’t get any more episodes to tell the story?

CUBITT: No, I didn’t, actually. One of the things I wanted to reflect is that the reality of these sorts of crimes is that it’s very difficult to catch the person who does them. The majority of murders are self-solvers because the person who did it is 10 feet away. Particularly male violence against women, it’s the boyfriend, it’s the husband or it’s the father. Whilst they might lie and come up with all kinds of fanciful stories, the police, with basic forensic work and logic, can go, “You know what? You’re responsible.” If there is nothing that links the perpetrator to the victim, then it’s really, really difficult. So, I just wanted the case to be complex.

It would not have worked, if I’d tried to condense it to five hours, so I took the gamble of them doing a second season. It would have been mildly a defeat, if they hadn’t done a second season, because The Fall would exist in five hours with him driving away, which would probably satisfy no one. It’s finely balanced at the end of the second season, but I still need to find a way of completely his story. But like all of these things, you gamble. You throw the dice and take a risk when you put it out there. If it works, that’s great, but as an artist, you have to hold your nerve. You do what you think you can do and what you think you should do, and then you offer it up for judgement and hope for the best.

If there is a third season and Spector is gone, can the story continue with a different serial killer?

CUBITT: I can’t answer that, at the moment. We’re in a situation where I’m very confident there will be a third season, but because of internal BBC situation, at the moment, it hasn’t been officially announced. I think the story can continue, but I’ll have to reserve judgment on that, until I get the green light and the go-ahead.

Do you have an ending in mind?

CUBITT: I do have an ending in mind. I think the problem for all these long-running series, even something as substantial as The Sopranos or Mad Men, is that wen it comes to ending those things, you simply cannot please everybody. There's no possible way around that problem. And we’ve seen good shows come to an end, like The Shield or The Sopranos, and many people were disappointed in the ending of The Sopranos. I had an experience when, after James Gandolfini had died, I went back and re-watched the final [season], and I have to say that, with the ending of The Sopranos, because I was mourning the loss of him as an actor, I found it incredibly powerful, and far more powerful than I did when I watched it the first time. It’s set up so that you think he is doomed, in some kind of way, and possibly even that members of his family are doomed, because it just goes to black. It took my breath away, watching it again. But equally, you recognize there are people who are going to go, “That’s not a proper ending. That’s an ambiguous ending.” As a writer, you reach that point where you decide that you’re going to end this thing, and you follow your instincts. You do what you think is best, but you cannot please everybody. There are bound to be people who call it unsatisfactory, in some kind of way.

The Fall is available on Netflix.