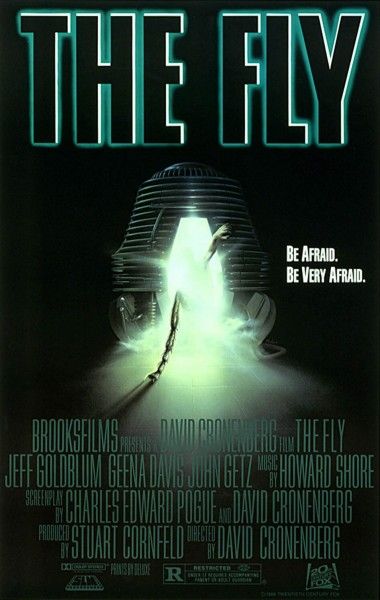

As the stories go, Jeff Goldblum and Geena Davis met on the set of the ignorable supernatural comedy Transylvania 6-5000, and began dating not long after. Their romance didn’t last – they often don’t in these situations – but they were still ostensibly together when Goldblum secured the role of Seth Brundle in David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly. The actor suggested Davis read for the part of Veronica Quaife, the journalist who falls for the tragic Brundle before he enters his telepod with an unexpected companion. Despite early trepidation on Cronenberg’s part about working with a couple, she got the role.

This certainly isn’t the most interesting bit of trivia to arise from the production of Cronenberg’s early masterwork. (For instance, Cronenberg was in pre-production on Total Recall when the offer to direct The Fly came in, and he passed the first time, before realizing that he couldn’t work with producer Dino De Laurentiis.) This fact does, however, give some insight into how deeply felt the relationship between Veronica – nicknamed Ronnie – and the man who becomes Brundlefly comes off in what is, at first glance, just a horror movie. Both Davis and Goldblum serve the script and Cronenberg well, imbuing their performances with revealing gesticulations, unexpected inflections, and quietly galvanizing facial tics. That’s only half of why the film works so well on a dramatic level, though. There’s a recognizable element of documentary and theater in watching a real life couple going through an unsettling, imaginary vision of a loved one’s terminal illness and subsequent transformation into a purely impulsive creature before meeting an ugly end.

One can feel the personal implications and investment that both Davis and Goldblum put into their roles from the moment their characters meet at a stuffy gala of sorts. There’s an easy chemistry from the get-go and their styles of humor, though used sparingly, comingle well in several remarkable scenes, both before and during the transformation. Their personal passion for the project wouldn’t be so potent, however, if not for Cronenberg’s own attachment to the material. The Canadian firebrand’s love for personalized design is rife throughout this film, but it’s also the gorgeous yet notably unfussy look of the film, his use of colors and his love for expressive, distinct faces.

Early on into the Brundle-Quaife relationship, Cronenberg tips his hat as to the film’s reflective meaning for him. The aforementioned gala ends with Ronnie going home with Brundle to see the great story he’s been teasing, only to realize that he’s building teleporting “telepods” that can beam inanimate objects through space and time. After seeing a test run of the ominous telepods – their design was inspired by a motorcycle engine part – she asks how Brundle was able to make all the technical equipment on his own. His answer is that he didn’t, and he goes onto admit that he’s something of a “systems manager” who fields work out to people far better suited to make his idea work. If you replace the words “systems manager” with the word “filmmaker,” and Brundle talked about the wardrobe people, production designers, and cinematographers instead of technical and scientific specialists, one can see where the film’s symbolic power is rooted.

The metaphor isn’t peerless, nor should it be, but the trajectory of the story suggests a cautionary tale for professionals who take their projects too personally or not personally enough. Not long after that aforementioned night at Brundle’s place, Ronnie signs on to report his work towards trials with living specimens, seeing a book at the end of the road rather than a good article. One of the first tests is on a baboon that, once teleported, looks like an amalgamation of everything you currently have in your fridge with bone particles scattered about. It’s during the trials that they fall for one another and it’s an off-handed comment in bed that leads Brundle to his first successful teleportation, but the celebration is ruined when Ronnie must go deal with Stathis (John Getz), her editor and former lover. Cronenberg, who re-wrote much of Charles Edward Pogue’s original script, aligns Brundle’s sudden decision to offer his own body as the first human trial with personal feelings of inadequacy and betrayal. And it’s these feelings that make him unaware of the little buzzing fly in the telepod’s window.

So, though Brundle feels rejuvenated after his first teleportation, deep inside his DNA, an infection, an unholy bonding, has begun. Cronenberg paces the transformation with a master’s tempo, with Ronnie incrementally seeing her once beloved at increasingly alarming phases of disintegration. The details, from the fingernail-pulling scene to the explanation of his vomit drop, are delightfully disgusting, but the human element of Brundle, and the film itself, remains. And Goldblum, who remains one of the best character actors on the block, does work that is equally heartbreaking and utterly chilling, wondrously expressing Brundle’s own knowledge of his physical and moral disintegration. In a late stage, Brundle warns Ronnie to not see him again and that he might not be able to control Brundlefly if she returns. The way he says “I’ll hurt you if you stay” still gives me the most unshakeable kind of chills and goosebumps, 30 years later.

It’s in that same scene that Brundle describes that the insect has no politics, devoid of compassion and driven by brutal instinct. Brundle is no longer working out of passion or curiosity but rather out of survival, and it’s this that Cronenberg seems to see as the sardonic undercurrent to an otherwise tragic story. The usage of videotape technology in the narrative seems to reflect a similar distrust of home video and the inherently capitalistic impulses that guide that business model, an idea that shows up in Videodrome and The Brood as well. That being said, to see this film exclusively in intellectual and thematic theories is precisely what Cronenberg seems concerned about. The distance from a director and his work precipitates the audience experiencing films at a remove.

One can pick up a lot of nods to philosophical and artistic influence, from the reference to M. Butterfly, another tale of transformation and wild passions, to the “plasma pool” diatribe paraphrased from an Alexander Pope essay. There’s plenty of cerebral thought at play throughout The Fly but it is primarily an emotional experience, and it’s that very balance that is Brundlefly’s conundrum. The audacious final sequence defies easy explanation, but the fact that Cronenberg and his performers are capable of making the killing of a 6-foot insect-monster so devastating, so lacerating is a testament to Cronenberg’s artistic and moral perspective. He makes the loss of Brundle to his own work an operatic tragedy of the highest order, even as it masquerades a brilliant argument against the continued push towards the impersonality of viewership, the continued separation of artist and audience. This dichotomy ultimately feels palpable between David and Goldblum’s characters from the very first time they enter Brundle’s apartment, when she asks him a pointed, fact-based question and is answered by Brundle playing the piano, another act based on technical skill that is nonetheless chiefly an emotional practice.