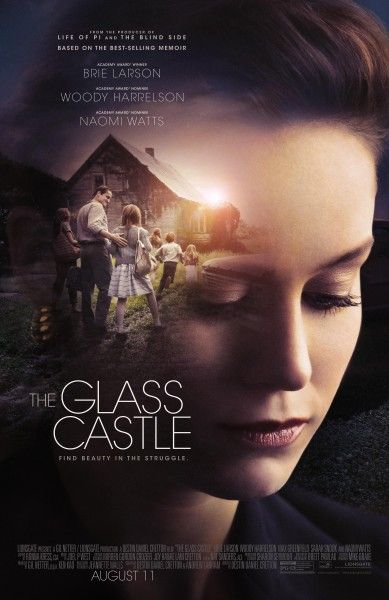

On the surface, Destin Daniel Cretton’s adaptation of Jeannette Walls’ memoir The Glass Castle, should pack an emotional punch. It’s the story of a painful childhood, the gulfs that form between parents and children, and the difficulty of finding forgiveness. The film also features outstanding performances, especially from Woody Harrelson who continues to show that he’s one of the best actors working today. And yet Cretton’s movie can never seem to find much depth beyond Walls’ suffering. Its heavy reliance on flashbacks drains the film of emotional tension, and Cretton struggles to find much insight on the strained relationship between Jeannette and her parents.

In 1989 in New York City, Jeannette Walls (Brie Larson) works as a gossip columnist for New York Magazine. One night, while driving home with her wealthy fiancé David (Max Greenfield), she spots her parents Rex (Woody Harrelson) and Rose Mary (Naomi Watts) digging through trash on the side of the street. The story then begins to flashback to Jeannette’s childhood and the struggles of growing up as transients with a father who was an alcoholic and a mother who rarely stood up for her children. The flashbacks are interspersed with the 1989 storyline as Jeannette tries to figure out how to cope with her homeless parents.

While the flashbacks are important, the fact that they’re flashbacks drains the movie of its tension. When we see all four Walls children in 1989, we know that while there are emotional scars (and in the case of Jeannette, physical scars), they’ve somehow survived the trauma and stuck together. When there’s a flashback devoted to Rex trying to kick his drinking habit, the power of the scene is undermined when we’ve already seen Rex resume drinking in 1989. Knowing how a story turns out doesn’t necessarily drain it of its power, but there’s a sad inevitability to Jeannette’s childhood where it feels more like a parade of sadness and neglect rather than something we’re living alongside her.

At some point, as misery makes way for more misery, we’re just left to say, “We get it, Jeannette Walls. You had a shitty childhood.” Cretton doesn’t let us get much further than that. We see the abuse as generational to an extent with the few brief scenes involving Rex’s mother, Erma (Robin Bartlett), but the movie rarely takes a wider view of poverty, which is a shame because there are times where the family’s situation feels tangible and immediate like being so hungry they’d eat butter and sugar because there was no real food in the house. But these moments usually give way to yet another cycle of Rex being a bad dad, Rose Mary being a bad mom, Jeannette trying to save her parents, and inevitably being let down.

It’s the kind of story that you can see working much better as a memoir as you really sit down and spend time with Jeannette and her family, but the narrative drive of a two-hour film gets stuck in a loop rather than letting you see Jeannette’s childhood and parents through her eyes. There’s a great deal of specificity in Cretton’s adaptation, but it constantly has trouble finding depth.

The film primarily draws its strength from the performances, particularly Harrelson. While Larson gets top-billing, she’s really more of a supporting performance as adult Jeannette only gets to be in half the movie whereas Rex and Rose Mary are in from start to finish, and the story is really about Jeannette’s relationship with Rex. It’s remarkable to see Harrelson at work here as he dives into the character’s complexities and contradictions, refusing to let us easily dismiss Rex as a mean drunk or a big talker. Through Harrelson’s performance, we see a man who genuinely loves his family, but is constantly consumed by his own anger and shame. It’s a fascinating portrayal even if the story doesn’t give the character much room to maneuver.

When we talk about stories being “unadaptable”, we usually mean it with regards to big, sprawling narratives that can’t be contained to a feature film. However, in the case of The Glass Castle, the problem is simply the medium and while some memoirs may work better as films, Walls’ story constantly meets the limitations of cinematic storytelling. Perhaps there was a more inventive way to tell her story than Cretton’s gentle, performance-driven approach, but the film we get never figures out how to effectively explore Walls’ childhood trauma. Much like the “Glass Castle” Rex keeps promising to build, it’s a compelling idea but the execution isn’t there.

Rating: C