Mario Puzo once paid a very high compliment to Francis Ford Coppola and his adaptation of Puzo’s The Godfather. Speaking to Charlie Rose in 1996, he said, “If you pick the 20 best movies of all time, you would have to include that movie. I don’t think you could say the same thing about [the book]. It’s a different thing, different evaluation.” Of course, without that book, there would be no great film, and Coppola’s Godfather is remarkably faithful to the source.

Even with Puzo co-writing the script, the adherence was unusual in Hollywood. Plot, character, sequence structure, and large chunks of dialogue come straight off the page. The chief differences are of omission and presentation; the film does without extensive subplots for minor characters, and it presents the main story more as an epic family tragedy than the (deliberate, well-crafted, and addicting) seedy pulp fiction style of the novel.

The changes necessary because of this difference in presentation tend to be small and subtle, but with impacts that ripple throughout the film trilogy. Among the most significant were those changes made to the Godfather himself, Vito Corleone.

Across The Godfather and The Godfather Part II, Vito’s role is in broad strokes and fine detail very close to Puzo’s book. Sent to America as a young boy to escape a mafia vendetta, he grows into a quiet and devoted family man (played by Robert De Niro in Part II), uninterested and unconnected to crime until a series of events tied to a local don awaken his violent ambitions. With an olive oil importing business as a front, he builds up a powerful mafia family of his own, based in gambling, prohibition, and political influence. A gangland war (the one section of his story omitted from the film) leaves Vito’s gang the first among equals in New York’s Five Families by the outbreak of World War II and affords Vito himself respect, affection, and fear throughout the city. The one fly in his ointment is the behavior of his sons: Sonny and Fredo disappoint him by entering into the mafia, while Michael (Al Pacino) disappoints through his defiance of all efforts by his father (played by Marlon Brando in the first Godfather) to aid or entice him with power. And so things stand at the beginning of The Godfather, wherein occur the events that shake Vito’s blood and crime families to their core.

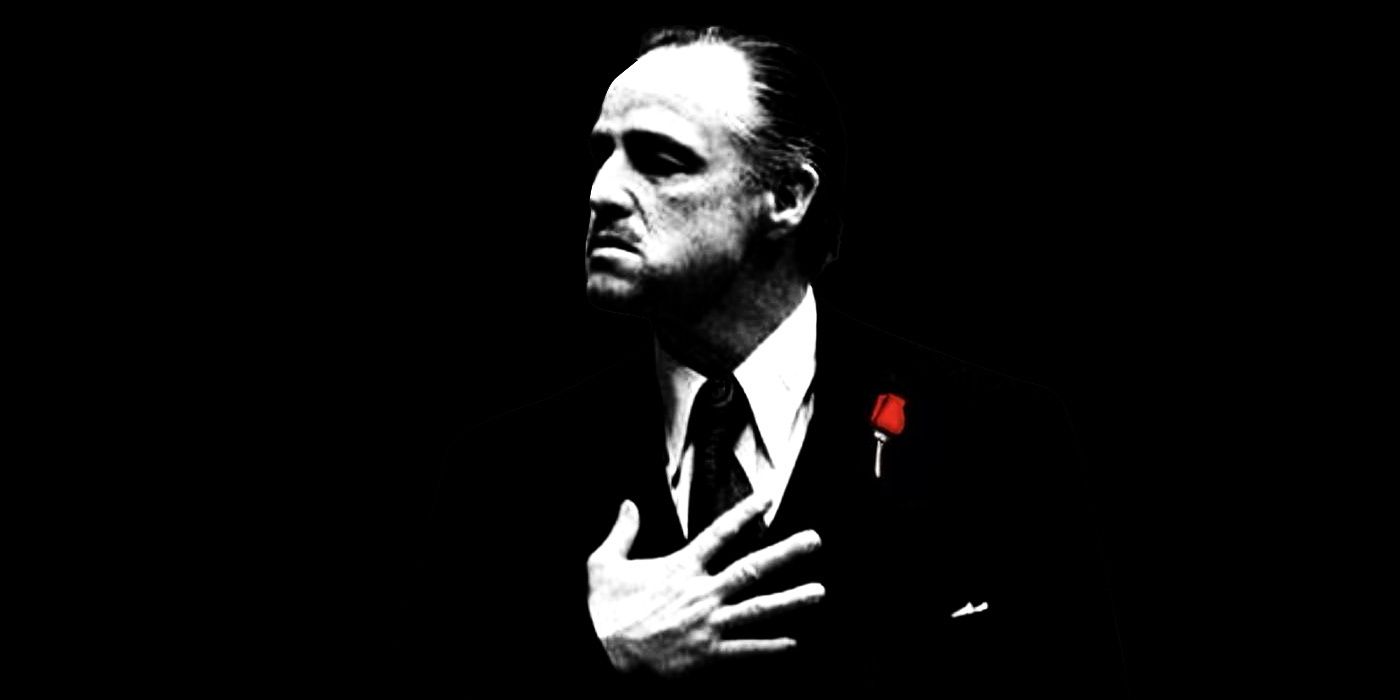

Literature and cinema both take pains to stress Vito’s power and magnetism. The attentions paid him by criminal underlings, political and business connections, and even his enemies are more akin to how to treat a king, not a criminal. But it’s on this point where the first difference between treatments of Vito emerges. The Godfather book alternates between an omniscient third-person perspective and a more limited scope through the eyes of various characters. This lets Vito occasionally be seen clearly through people not under his spell. A doctor looks at him and sees not a regal patron and all-powerful chieftain, but a squat man in an ill-fitting tuxedo who is only impressive through his simple practicality about a dying man’s wishes. A movie producer at the receiving end of Vito’s machinations, while in a panicked mess of racing thoughts, aptly summarizes the unjustifiably ruthless and relentless nature of the mafia’s “justice.” Michael himself, while hiding in Sicily, sees the devastation that the mafia has inflicted upon its homeland and imagines that his father’s ways could do the same to America if left unabated.

The Godfather trilogy makes no bones about the horrors of the mafia and the price paid by the Corleones for their persistence in the life, but there is no stepping outside their world to comment on it in the films. There’s no inner monologue by Jack Woltz about the horrors done to him, no time taken by Michael for introspection on his father’s impact on society. These things can be easily intuited by watching the first two films, but they aren’t stated so bluntly. As a consequence, Vito’s regal aura is never punctured on celluloid. Nobody in the first movie looks at Brando in that tux and sees an unremarkable peasant; he’s always presented as a grand figure.

And a more benevolent figure, at least on the surface, when compared to the novel. Contrary to the famous line, every act of violence committed or ordered by Vito Corleone in The Godfather and The Godfather Part II is personal, not business. His first act of crime (unwittingly helping to steal a rug) is done so he can have something pleasant to bring home to his wife. He murders Don Fanucci after the don threatens Vito and his family. A landlord is threatened for the sake of a little old lady. The murder of Don Ciccio in Sicily satisfies a vendetta born when Ciccio kills Vito’s brother and parents. The horse head in the bed? A favor for his godson. It’s only the rival gangsters who kill and maim in the name of business. Left unshown is Vito’s underhanded rise to power from the book: the rival olive oil importers terrorized or disappeared, the brutal torture of Chicagoland gangsters sent as hired guns, the indirect intimidation of even his closest associates. By limiting the target of his violence to those who threaten his loved ones, the films retain the horror of Vito’s actions but couples them with a more emotional and human motive.

This humanizing aspect is reinforced by the performances of Brando and De Niro. Vito’s charisma, tact, and “reasonableness” with people are frequently mentioned in the novel, but in keeping with the magisterial air awarded to him by others, he’s often detached from even those he loves most. There’s a coldness to Puzo’s Vito even when he shows personal affection. That isn’t true of the films’ Vito. Visually, Brando and Pacino are often dressed in earthy colors and elegant but simple suits, grounding the character in his rustic roots. As the young Vito, De Niro is gentle and loving in scenes with his wife and children and often mischievous, even playful, when attending to business. His handling of the landlord is almost a practical joke before it’s a real threat, and even when plotting Fanucci’s murder, he gives his partners Tessio and Clemenza sly, indirect reassurances with a good-humored smile. Brando gave the older Vito a rough but straightforward manner in business and a tough but affectionate one in family matters. Where Puzo’s Vito need only brace himself against the undertaker’s shoulder at the sight of his eldest son’s body, Brando cries, as he does when Michael stays in the hospital to defend him. Though Vito’s final moments are spent with his grandson in the book, it was Brando who devised the orange “monster mouth” and the subsequent game played in the garden, injecting some sweetness into the don’s final moments.

The sum total of these small adjustments is a character who presents very differently on film then he does on the page. Cinema’s Vito is one who, as Coppola put it on the DVD commentary, outwits the devil: he was able to lead an evil life as a mafia don while convincing his family, himself, and the audience that he was a good man. He was a character who could be at peace with his actions and compartmentalize his empathy and humanity as necessary. The only regret he seems to have about his life is that he couldn’t keep Michael from getting involved in crime.

This luxury of self-deception was denied Michael, and this is where the changes to Vito most benefit the film trilogy. For all of Michael’s early resistance to his family’s way of life, the book is never shy about highlighting the similarities between him and his father. Michael’s magnetism, business manner, cunning, and ruthlessness are those of his father; more Americanized, perhaps, but essentially the same. In the film, Vito’s greater warmth via Brando contrasts sharply with the coolness of Pacino’s Michael. The gap between them is only so wide at the beginning of the film; Michael’s humanity still shines through in his romance with Kay (Diane Keaton). But in entering his father’s world, Michael proves unable or unwilling to outwit the devil and maintain his humanity, a contrast that becomes more apparent in The Godfather Part II. Michael can’t offer a mischievous smile, a comforting image from a warm suit, or an easy and genuine affection for his blood. His business manner is impersonal, his general demeanor is cold and intimidating, and his violence streak manifests itself through explosive rage. He does love his family, but he can’t unify them, maintain a façade of benevolence, or forgive any actions they take against him.

This inability of Michael’s to sustain the family, not part of the book, deepens the tragedy of his descent from an idealistic young man to another mafia boss. But it wouldn’t register as strongly as it does without that central contrast between him and Vito. The end of Part II and The Godfather Part III (a severely underrated film) drive this home. Part II juxtaposes a family gathering for Vito’s birthday, with everyone young and happy and devoted to him except for Michael, with Michael’s lonely brooding after banishing his wife and murdering his brother. And while The Godfather Part III doesn’t intercut with footage of Vito’s death, it does echo it in a broad sense: the father dies happily playing with his grandchild in the garden, while the son wastes away in a courtyard after his perpetuation of the family sins cost his daughter her life.