There is a long and complicated history behind big-screen adaptations of the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, and that landscape is littered with the remains of countless scripts and projects that never saw the light of day. Peter Jackson’s epic trilogy was exceptional in more than one way: not only did it come away with trophies and superlatives galore, but it also was the first major production of The Lord of the Rings to be completed in a live-action format. It was one of the rare cases in which a Tolkien-based script actually came to production in the first place.

There were a handful of other successful attempts before Jackson came to the helm, however. Ralph Bakshi made the incomplete animated Lord of the Rings in 1978; the Rankin/Bass duo also brought versions of The Hobbit and The Return of the King to the screen in the 70’s and 80’s, but the very first film adaptation of Tolkien’s world has such a wild and strange story that it deserves to be more widely known.

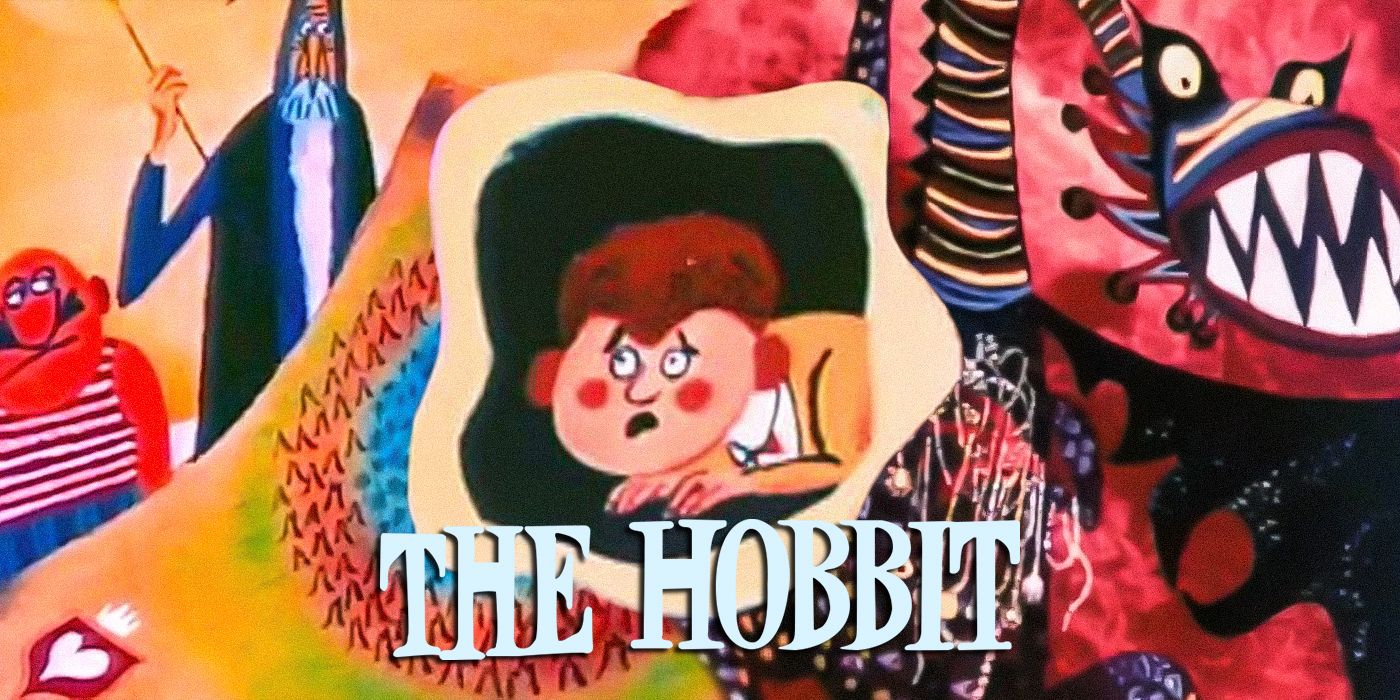

The Hobbit (1966) is… a bizarre movie, to say the least. It is 12 minutes long, and only bears a passing resemblance to the story told in the book. Thorin Oakenshield is a general from Dale, and none of the other dwarves ever show up in the story. Gollum has his name mysteriously changed to “Goloom,” Goblins become “Grablins,” the trolls become creatures called “Groans,” and the dragon Smaug is called “Snag.” Bilbo does find the magic Ring, but never disappears or does anything in particular with it. There is also an invented “Princess Mika” of Dale, whom Bilbo marries at the end of the story. Together with her and Thorin, Bilbo makes an arrow with the Arkenstone and shoots the sleeping dragon Snag. It’s… weird. The most fascinating thing about the movie, though, is how this strange film came about in the first place.

The movie itself was written and directed by Gene Deitch, who had some respected accolades of his own in animated movies before taking on the project of The Hobbit. He had worked on episodes of the animated Popeye and Tom and Jerry series, and directed the 1961 Academy Award-winning animated short Munro. According to his own account, the actual story of the making of the movie was one that began with great promise before crashing and burning in a spectacularly unexpected way.

Deitch was initially brought on to the project of making a Hobbit movie in 1964 by his producer, William Snyder. Snyder had bought the rights to a then little-known children’s book called The Hobbit, which he was interested in turning into a feature-length animated film. The rights to the project extended until June 30, 1966, which left around two years to complete the movie. After reading the book and thoroughly enjoying it, Deitch got to work with a grand vision in mind. He proposed some cutting-edge new animation techniques that would help to visualize Tolkien’s world, and secured the commitment of the excellent Czech artist, Jirí Trnka, to do the animation. Then, everything began to unravel.

From the outset, Deitch had played very loosely with the plot of the source material. The Hobbit was, as far as he knew, a relatively unknown story that was charming and entertaining, so he was using it as inspiration more than as a source for direct adaptation. He had changed names, added characters and songs, and tweaked the plot in the service of his creative decisions. However, the ground then shifted beneath his feet. After a copyright dispute with Ace Books in 1965, Tolkien released a second American edition of The Lord of the Rings, where the affordability of the book and the well-publicized dispute took the popularity of Tolkien’s works to the stratosphere, and made Deitch aware for the first time the magnitude of what he was working with. The only problem was that he was already halfway through his script.

Deitch then reworked his screenplay so that it might leave room for the story of The Lord of the Rings, an editing process which meant that the writing of the script took him the better part of a year. However, after his work and revision, he finally came to New York in January of 1966, where Snyder made the pitch to the studio for the animated Hobbit movie. The studio, however, unaware of the appeal of Tolkien and balking at the projected cost of the movie, killed the project.

So far, this was an unfortunate but hardly uncommon experience; plenty of scripts never reach the screen, after all. It was the epilogue to this story, though, that made for the wild and weird product that eventually did reach the screen.

The problem for Snyder was that his rights were set to expire on June 30 of 1966, and the studio had just torpedoed his film. If no movie were made, the rights would revert to the Tolkien Estate and his investment would have been for nothing. However, if they were able to cobble a film together in time without the studio budget, his film rights would be renewed. The contract stipulated that a full color Hobbit film had to be screened for a paying audience by the expiration date of the contract. With that in mind, Snyder called up Deitch in Prague and set for him the task of producing a 12-minute color animated version of his script that could fit on one reel of film and could be screened in New York on June 30. Deitch, consequently, set to the task of gutting his script to put together enough continuity for a short film, which he had to animate, film, cut, edit, and narrate — all in exactly 30 days.

Deitch somehow accomplished this, finding a new animator and pulling strings with one of his friends to record a narration and another to produce a soundtrack. The animation, far from Deitch’s original groundbreaking ideas, had to be done mostly with paper cutouts being dragged across the camera lens. When, somehow, Deitch completed the project in time, he flew back to New York, where Snyder had rented a screening room for June 30th. On the day the contract expired, Deitch then wandered around the streets talking to random strangers until he had a handful of people willing to come to this screening. In order to fulfill the contract, they had to be a paying audience, so Deitch gave each of them a dime, which they then gave back to him as payment. The film was screened in time, and the rights were renewed, which Snyder then immediately sold back to the Tolkien Estate for $100,000 (a price which had skyrocketed due to the recent popularity of Tolkien’s books).

That is how the first film adaptation of Middle-earth came to the screen. The movie itself was never seen by any other audience beyond the bemused handful of New Yorkers in 1966, until the short film found its way to YouTube in 2012. The wild strangeness of the movie itself is matched, if not surpassed, by the crazy adventure of twists and turns that led to its creation in the first place, but digging around in the story of its production reveals a testament to the bizarre and complex process that brings any movie to the screen, and the innumerable reasons why so many films never get even that far.