Big movies – really big movies, cultural phenomena that serve as markers for entire decades – can attract legends around them, with varying degrees of truth. There’s no hanging man in the background of The Wizard of Oz, no one died in the chariot race of Ben-Hur, but Apocalypse Now really was plagued with typhoon-ravaging sets, Martin Sheen’s heart attack, and Marlon Brando’s mercurial attitude.

The Lion King has no stories so life-threatening attached to it, but it has attracted its share of rumors and urban myths since 1994. There’s the still lingering charge that it stole from Osamu Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion, a subject for another day; for now, suffice to say while similarities exist, so do massive differences, particularly in the plot. But a more oft-discussed, less accusatory claim is that The Lion King is an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Significant narrative parallels are more evident there: a king betrayed by a wicked brother; a young prince visited by the ghost of his father; a violent confrontation of truth, vengeance, and succession in the finale. Yet dynastic struggles of this kind are hardly rare in fiction. So, is there a debt owed by Disney to the Bard?

The answer is yes, but not so large a debt as some would have you believe.

The Lion King wasn’t Disney’s answer to the likes of West Side Story or Throne of Blood. That is to say, it wasn’t conceived as an adaptation of Shakespeare. At the time of release, The Lion King was unique in that it was Disney’s first full-length animated feature that wasn’t an adaptation of any specific source material. The film’s origins come from, of all things, a plane ride conversation between executives Jeffrey Katzenberg, Peter Schneider, and Roy E. Disney. The topic of Africa came up, as did Katzenberg’s recollections of a rough time in his early life in politics. This led them to consider a coming-of-age tale with lions, and development began on a project then called King of the Jungle. The initial concept would have lions warring against baboons, with the leonine princely hero tempted to a life of sloth by the villain to better facilitate his overthrow. Potentially fun, but a far cry from any tormented Danish royalty.

King of the Jungle’s first assigned director was George Scribner, fresh off Oliver & Company. By now, the project was known within Disney as “Bambi with lions.” Scribner’s approach to this brief was a very naturalistic one, a National Geographic documentary style that would feature “nature, red in tooth and claw.” But this interpretation clashed badly with that of Roger Allers, one of the chief story artists behind The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast who was promoted to co-director on King of the Jungle. While the two men got on personally, they struggled to reconcile visions for the movie, a struggle that a trip to Africa and the arrival of producer Don Hahn couldn’t resolve. When the songwriting team of Elton John and Tim Rice joined the project, Scribner objected. He was replaced shortly after by Rob Minkoff, an animator who had never directed a feature before.

With two first-time directors and a storyline still in flux, King of the Jungle attracted negative attitudes among many in Disney animation. Pocahontas was in production at the same time, and many of the top talent at the studio flocked to that film. Despite his pivotal role in the film’s origins, Katzenberg openly declared that King of the Jungle had uncertain prospects compared to the sure-fire hit that Pocahontas undoubtedly was. This B-movie treatment at the hands of the company didn’t help bolster the confidence of Hahn or the directors, but it did attract a dedicated crew determined to show that the film was worthwhile. With head of story Brenda Chapman, Hahn, Allers, and Minkoff settled the structure of the story as a dramatic journey from childhood into inheritance and responsibility, presented on an epic scale and leavened by musical comedy. They also changed the title to the one we now know – The Lion King. Broad inspiration came from the Biblical stories of Joseph and Moses, and from Bambi, of course. But no one was talking Shakespeare yet.

Along the development road, the idea of lions and baboons waging war fell by the wayside in favor of a struggle among lions. The usurping villain of the piece, now called Scar, was initially conceived as an outsider to Mufasa’s pride. Speaking on a DVD release of The Lion King, Allers recalled that, as the story continued to be revised, they felt it would be more interesting if the threat to Simba came from within the pride. With that step taken, it was noted that an even greater threat to the royal family would come from within the family itself, so Scar was made Mufasa’s brother. It was only at this point, in a pitch session to Katzenberg and other executives, that someone noted the parallels to Hamlet.

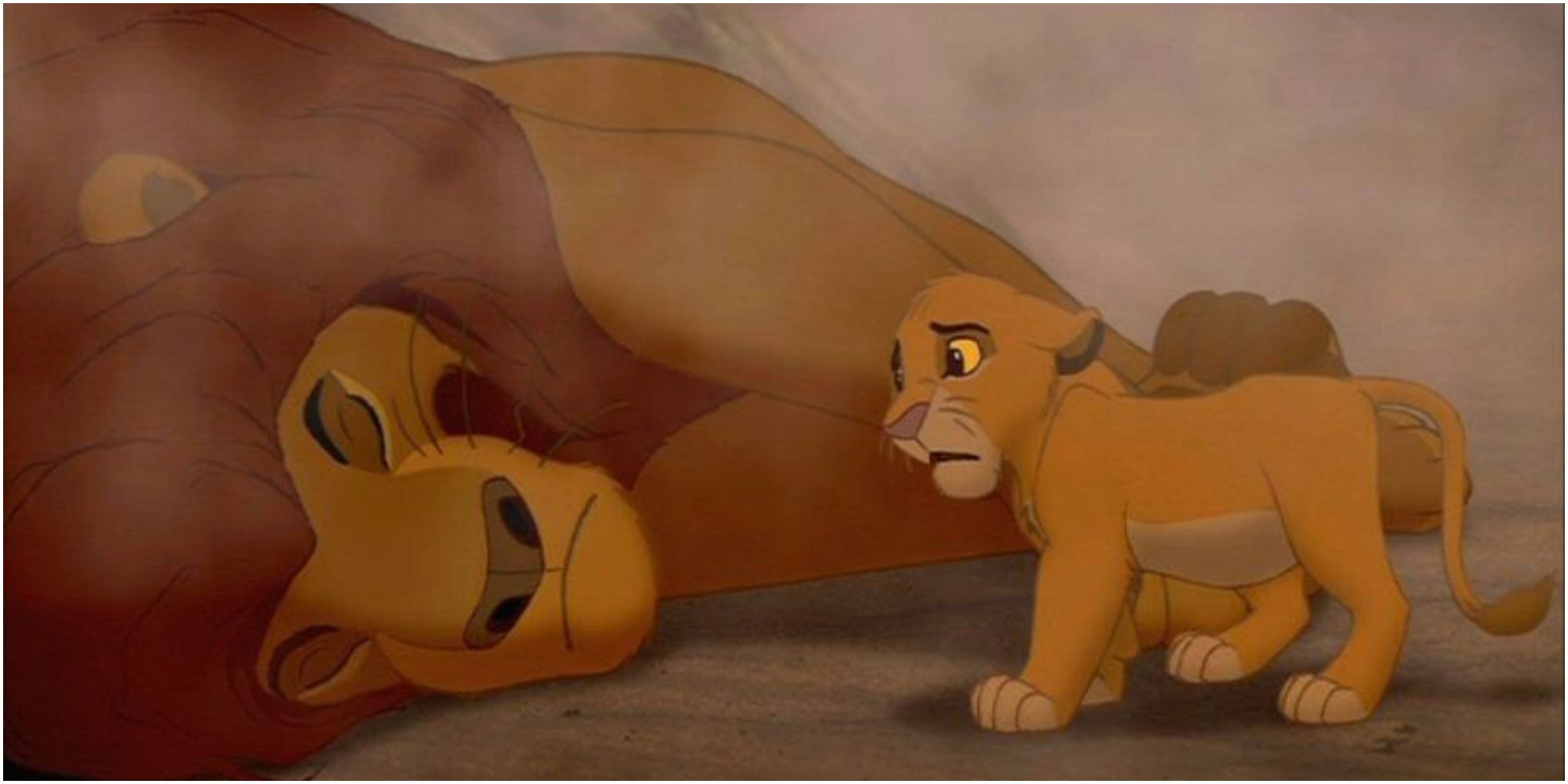

If the creative team behind The Lion King didn’t set out to evoke Shakespeare’s most famous play, once they realized the similarities in their story, they didn’t shy away from them. The sales line of “Bambi with lions” became “Bambi with lions and Hamlet thrown in” when screenwriters Irene Mecchi and Jonathan Roberts were brought in for final revisions – “Bamblet,” Mecchi called it on the DVD. She took inspiration from Shakespeare’s structural instinct to follow scenes of horror or tragedy with uproarious comedy (though Walt Disney himself, among countless others, have had the same instinct). The story team referred to a certain scene that they needed as a “to be or not to be” scene. The moment in question: the immediate aftermath of Mufasa’s ghostly visit to Simba. It became the last scene added to the film. But the team would only go so far in evoking Hamlet. When a version of Mufasa’s death had Scar utter the words “good night, sweet prince,” things became, in Hahn’s judgement, “too self-conscious.” But Scar playing with a wildebeest skull? That was fine.

Stumbling into parallels with Shakespeare’s work, then embracing them as one of many weighty influences, served The Lion King well; to this day, it reigns as the most successful traditionally animated movie. Hamlet may not have been its source material, but its ties to Shakespeare have, if anything, only become tighter with time. The Lion King spawned one of the more tolerable direct-to-video sequels of the 2000s, The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride, a film that gradually stumbled onto parallels to Romeo and Juliet. It also spawned one of the least of the sequels, The Lion King 1 ½, which took more deliberate inspiration from the Hamlet-derived play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. The lifeless CGI remake managed the feat of grossing over $1 billion dollars worldwide without leaving any discernable impact on popular culture; any movie so derivative would inevitably reflect the inspirations of its source material, so the Hamlet connection lives on even there. And while The Lion King play is no more derived from Hamlet than the source film, it makes use of Shakespeare’s original medium. The result was, in my opinion, the only one of Disney’s Broadway shows that is as good a play as the original is a film. Considering how good the original Lion King is as a movie, that is no small feat.