A ghost is something that should not be, intruding on a world it does not belong to. A ghost is an interloper. The same could be said of rigid social hierarchies, especially like the mid-20th century ones depicted in Lenny Abrahamson’s adaptation of The Little Stranger. It’s a movie obsessed with class and the shifting power structures of post-war England where the aristocracy has largely faded and professionals like doctors are rising. The subtext is certainly interesting, and it’s clever to tell this shift within the context of a ghost story, and yet the movie lacks an emotional punch to hammer home its observations.

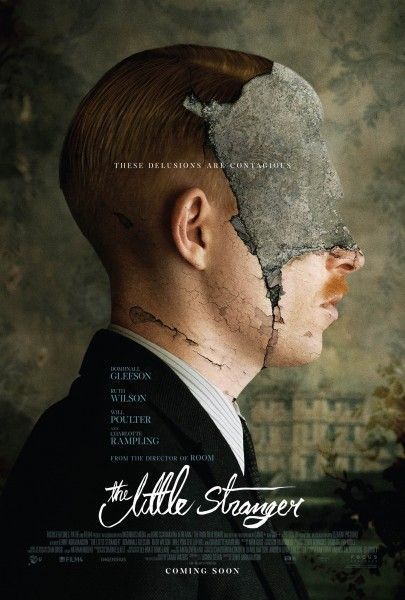

Dr. Faraday (Domhnall Gleeson) is a physician working in the English countryside when he’s called to check in on the tenets of the dilapidated Hundreds Hall, a fading manor where his mother once worked as a housemaid. There he tends for the Ayres family, including Caroline (Ruth Wilson), who catches Faraday’s eye; her brother Roderick (Will Poulter), a badly scarred veteran suffering from war shock; and their mother Mrs. Ayres (Charlotte Rampling). However, whenever Faraday comes to call on the Ayres family, strange and horrible things start to happen that might be connected to the ghost of the Suki Ayres, a deceased sibling of Caroline and Roderick who died before either were born.

However, it becomes clear fairly early on (especially if you notice the acorn in the title card) that the “Little Stranger” refers not to the late Suki Ayres, but more appropriately to Faraday. Faraday is obsessed not so much with the Ayres family but with what they represent. He fondly remembers a day from his childhood thirty years prior where he and his mother were invited to Hundreds Hall and he briefly tasted the life of the aristocracy. The person haunting the Ayres doesn’t seem to be so much the ghost of little Suki Ayres, but Faraday, who wants to climb beyond his station even though he is objectively more powerful than the faded Ayres clan and their rundown manor.

And yet once you’ve put all the pieces together, there’s not much that’s satisfying about The Little Stranger. I love gothic horror stories, but Abrahamson never leans enough into the horror to make the film particularly scary or haunting even though Faraday is a creep, and the period details are too bogged down in the horror mystery to ever really come alive. It’s a movie with a very clear subtext on its mind, but once you acknowledge that subtext, there’s nowhere to go any further with it. Perhaps English viewers will get more out of the experience, but the specificity of the conflict ends up working against the emotional impact of the picture.

It doesn’t help that The Little Stranger is an extremely cold picture, from the performances to the cinematography to the music. It’s a movie that’s meant to put you at a distance. Perhaps it’s so that we feel the distance between Faraday and his desire to be an aristocrat, but it fills the movie with stagnant air, like it’s afraid to breathe for fear of being seen as human. The story tells you the emotions, and because you can see everything telegraphed out, it makes for a rigid, lifeless picture that has more on its mind than it has in its heart. You don’t really feel for anyone in this movie, but you do come away thinking a bit about class distinctions.

The Little Stranger is a movie that could best be described as “interesting.” It’s got something on its mind, but what’s there isn’t particularly deep or intriguing. It’s a clever concept and conceit, but it doesn’t serve much, and Abrahamson plays his film so quietly that it never raises above a whisper. You’re left wondering what kind of impact The Little Stranger was supposed to leave. Sadly, The Little Stranger is so hushed, quiet, and diminutive, that it’s hard to see much of anything at all.

Rating: C-