With a news cycle that moves so fast (it was 10 days ago that we caught the President trying to extort an election official into fraud, remember?), things that happened in the 2000s can feel like ancient history. America is a country that likes to forget because it’s always obsessed with the shiny, new things, which leaves a lot of sins as yesterday’s news rather than something that needs a serious reckoning. Thankfully, we have folks like Kevin Macdonald making movies like The Mauritanian, which refuse to let us forget the injustices done in our name. While at first glimpse the film may seem like yet another liberal polemic preaching to the converted, The Mauritanian comes alive thanks to the incredible work from its lead actor, Tahar Rahim. While there are bigger names surrounding him, this movie belongs to Rahim, and he gives an unforgettable performance as a man forced into horrific, Kafkaesque circumstances without losing his humanity. The Mauritanian isn’t meant to serve as a hagiography, but a reminder of how much we lost claiming that we were keeping America safe.

In November 2001, Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Rahim) was arrested by Mauritanian authorities where he was shipped around the world and interrogated before eventually landing in Guantanamo Bay despite never being formally charged with a crime. In February 2005, his case finally comes to the attention of civil rights attorney Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster), who believes that the only way justice can function is if it functions for everyone. However, at the same time, the government has its own lawyer, Stu Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch), working the case to get Slahi the death penalty. The government claims that Slahi was Al-Qaeda’s chief recruiter for the 9/11 attacks and had direct contact with multiple perpetrators. The film then jumps around between Hollander’s investigation, Couch’s investigation, and flashbacks to what actually happened in Slahi’s life that landed him in Gitmo.

By moving between these different timelines, Macdonald does an excellent job of keeping up the pace of his movie while never letting us completely settle into what happened in Slahi’s case until we reach the climax of the movie. While you could argue that The Mauritanian is predictable, that’s a more damning indictment of U.S. foreign policy than it is of how the film is plotted. Yes, it’s clear where the story is headed, and yet Macdonald keeps us riveted by seeing how the characters watch the narrative unfold. Hollander isn’t some perfect saint and Couch is by no means a villain. The only place where the film truly falters is when it does try to introduce some one-dimensional nefarious operative like Couch’s friend Neil Buckland (Zachary Levi), who feels like a composite created out of narrative convenience than someone who illuminates the real-world stakes of the film’s conflict.

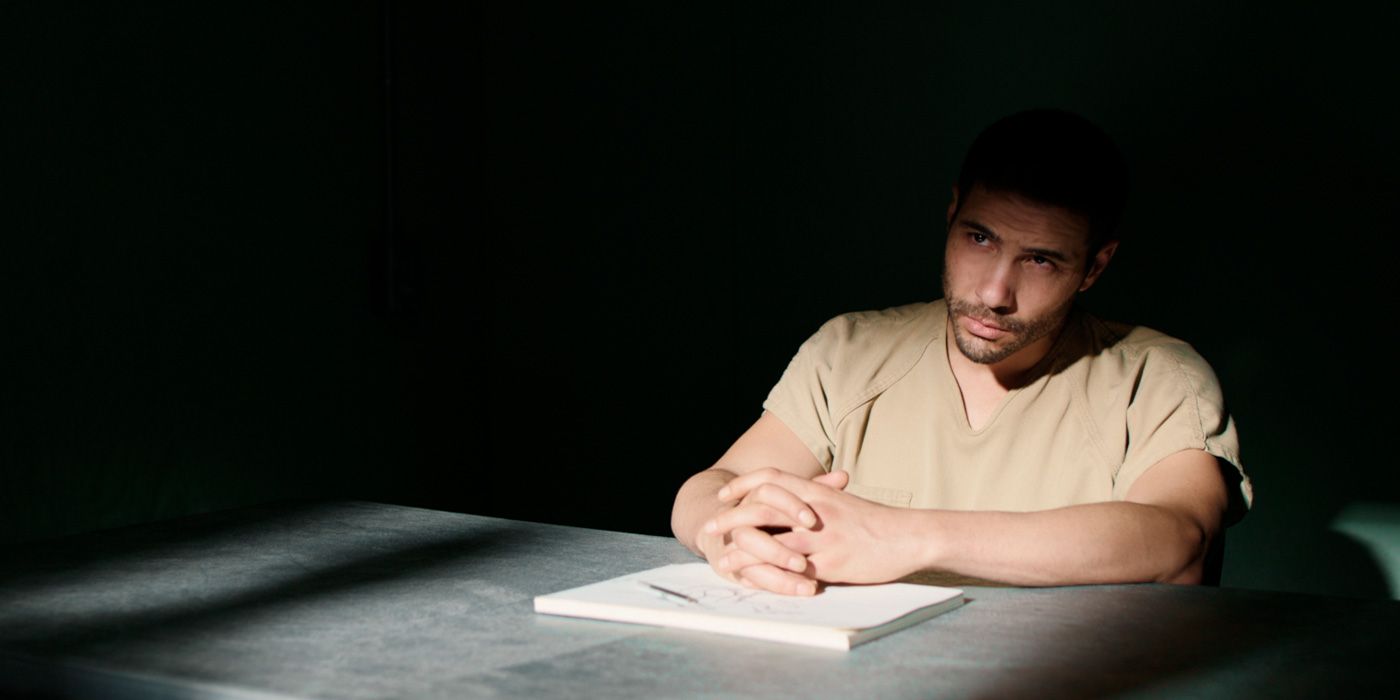

Thankfully, all of these supporting characters are really in service to telling Slahi’s story, and that’s where Rahim gets to carry the movie. Some may wander into The Mauritanian wondering why there’s not more of bigger stars like Foster or Cumberbatch, but I hope they’ll be pleasantly surprised by the tremendous work done by Rahim (and then hopefully seek out his 2009 movie, A Prophet). All the emotions and narrative stakes ultimately rest on him, and the magic of his performance is that he knows how to make Slahi charming enough while still leaving us wondering, “What if he actually did it?” By working to convey Slahi’s humanity and complexity, there’s an excellent everyman quality to the performance. It’s the kind of role that would earn Tom Hanks numerous accolades if a white guy could ever be imprisoned for years in Guantanamo Bay without being charged with a crime.

Watching Slahi’s story unfold really hammers home in stark detail of where we were less than 20 years ago with the War on Terror. Again, the news cycle moves so fast that there’s not really a reckoning, and in the case of the Obama Administration, there was complicity in these cases rather than holding the Bush Administration accountable for wreaking havoc on the legal system in the name of defense. The most sickening parts of The Mauritanian are when characters proclaim that these kinds of horrific acts must be done to save American lives. And yet here we are now with 4,000 people dying every day from a plague, and all those people are notably silent about the value of human life because as we can see from Slahi’s case, it was never about preserving life; it was about preserving power, and power is the ability to pluck a guy out of Mauritania and steal years of his life because some Washington goons want to feel like they’re doing a good job. That’s what American power looks like.

The delicate tightrope that The Mauritanian walks is never trying to make this a story about the triumph of the human spirit nor a polemic on how these sins only belong to a few bad apples. What makes Slahi’s story so infuriating and horrifying is that it probably isn’t that uncommon. Anyone who had even a passing familiarity with Al-Qaeda, even when Al-Qaeda was fighting with America against the USSR (as was the case with Slahi), became a target for a country desperately trying to show “strength” in the wake of its biggest security failure. Through Slahi’s story and Rahim’s incredible performance, The Mauritanian shows us the cost of what happens when we allow America to commit atrocities and hope that it will be forgotten by the next news cycle.

Rating: B+