"I will civilize this place," Ray Winstone's Captain Stanley declares twice in the opening minutes of 2005's The Proposition. The place he speaks of is a slice of Australian Outback, a pocket of a vast desert expanse relatively untouched by the expanding British Empire during the late 19th century in which director John Hillcoat's western takes place. But the former half of Winstone's declaration is not as easy to define as the latter. What does he mean by civilize? The irony of Captain Stanley's pursuit of "civilization" is that every value the British colonizers view as civil is just as prominent in those they've deemed savage as it is in their own kind, and every quality they view as evil runs just as rampant in their own system that they seek to impose. Not only is the enforcing of "civilization" a backwards concept, but it also leads to enough violence and bloodshed to place The Proposition amongst the most brutal films of the 21st century.

Before the movie begins, the small village that Captain Stanley earned his title patrolling is the site of a barbarous crime: the rape and murder of a family. Its information presented with restraint through a montage of photographs during the opening credits sequence. Music icon Nick Cave pens this screenplay in a way that lets the offscreen tragedy loom over the Outback, but the lack of its depiction allows the horrors of the next 100 minutes to stand on their own. It allows the audience to view the violence that coats the rest of the film as not without cause but certainly unjustified.

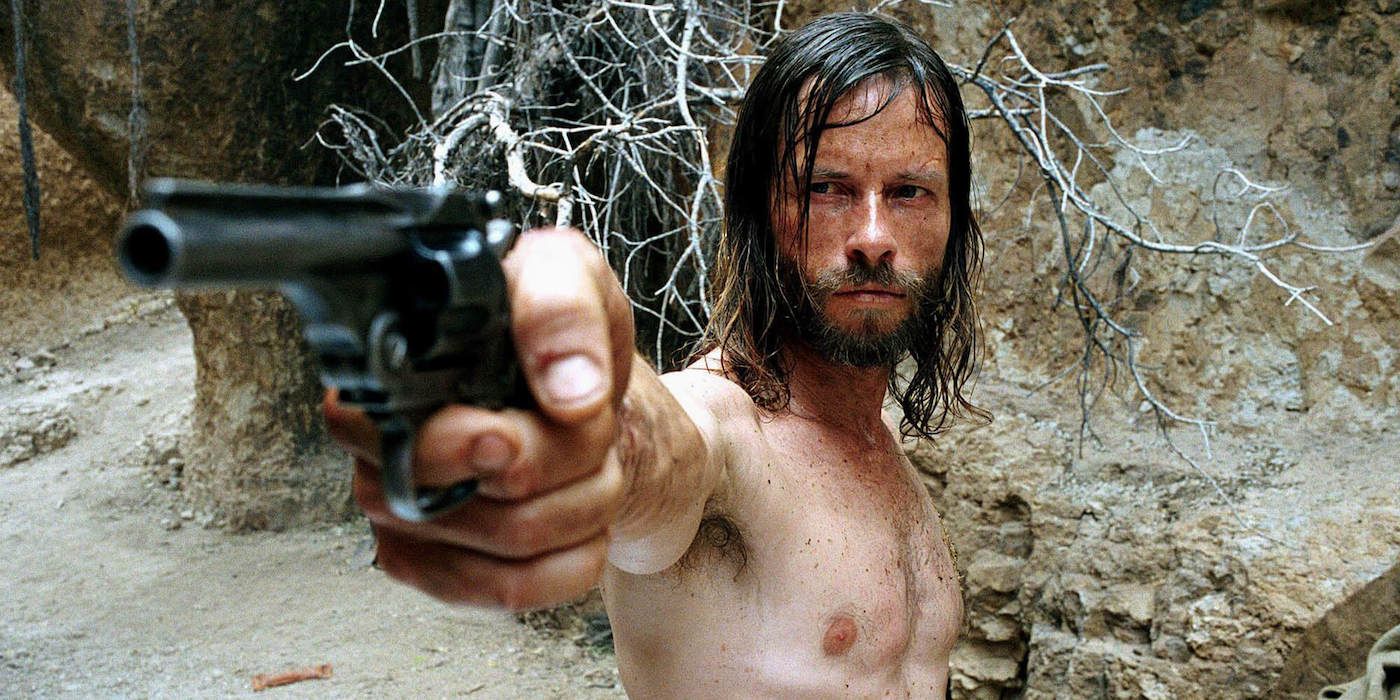

The opening scene shoves the audience straight into the fray. Guy Pearce's Charlie Burns and his younger brother Mikey, a pair of outlaws, are thrust into a scene where a barrage of bullets clanging against metal is the only thing discernable. Before the characters or audience know what's hit them, Captain Stanley has captured the two Burns brothers and presents Charlie with a proposition: he has nine days to hunt down and kill his older brother Arthur, the man guilty of the rape and triple homicide. The life of Mikey is what Captain Stanley holds as collateral if Charlie refuses or fails. The choice for Charlie is painful but ultimately inevitable, as he values the life of his younger and more innocent brother over Arthur's.

Captain Stanley flexes his authority in the opening scene, offering a glimpse of the sort of power he has the ability to wield. But after this introduction, the entirety of Captain Stanley's capacity to impose his will evaporates. For a figure whose role is to impart strength, he is rendered completely helpless by those who awarded him authority. His plan is one that possesses the possibility of rehabilitation, the ability to heal the two brothers who seek to escape their violent past while punishing the one who pursues carnage (Charlie and Mikey's role in the rape and murder is never explained but is implied as tangential). Despite all the fire that seems to burn under Stanley's brow, despite the cruel nature that his plan hinges upon, the vision he pursues is one in which civilized society is built upon reform and restoration instead of violence. But of course, his vision is not the one that will end up being employed.

David Wenham's Eden Fletcher, a man whose title is never defined but he appears to be some sort of constable, is the type of bloodthirsty figure who seems to always be granted authority. In a film in which every character wears a layer of dirt on top of their clothes, where it's difficult to find a head which a hoard of flies isn't circling, he rides through town atop a white horse dressed to the nines. His presentation suggests not only authority but admirability, but only serves as a means for him to justify his brutality. His view of civilized society consists of the extermination, in one way or another, of the non-British. He views the Burns brothers (who are Irish) as filthy vermin, not people who have the capacity for rehabilitation because they never should have been given a chance to showcase their virtue in the first place. And it goes without saying that he considers the aboriginals as subhuman as well, brutalizing the ones who don't submit to servitude in his town, saying at one point "If you have to kill one, make bloody well sure you kill them all." Fletcher wants to give Mikey 100 lashes for his involvement in his eldest brother's crime, knowing very well the flogging would likely kill the boy. Captain Stanley can and does put a gun to Fletcher's head when the constable and a mob of townsfolk approach the jailhouse with whip in hand calling for Mikey's head, or rather his back. Captain Stanley briefly halts the angry mass, but he ends up powerless to the will of his wife.

Emily Watson's Martha Stanley is class personified. She exists in a realm where the British definition of prim and proper reigns supreme. She wears dresses somehow un-smudged by sand and dirt and takes baths in a region where water feels like a foreign concept. She has built a garden outside of her house where she cultivates shrubs and roses. She embodies grace, but also the British superiority mindset that governs their quest for expansion. The greenery that she attempts to grow is completely out of place and un-embraced by the nature of the Outback's wilderness, but her refusal to adopt the nature of her new home makes her all that more intrusive. She also possesses the mindset that violence is the only just punishment for violence. Upon hearing that Mikey Burns played a role in the rape and murder of her friends, she uses the love her husband has for her as leverage to bring the youngest Burns boy to her idea of justice.

It's a thoroughly disturbing scene as Mikey's is flogged over and over. As horror spills out across the village, Martha along with the previously vengeful townsfolk come to the realization of exactly what they've done. Not only have they sealed their own fate, they have also become the perpetrators of the same type of crime they vowed to eradicate. It was a reliance on the morals of those clothed in suits and dresses that resulted in the continuation of lawlessness and inhumanity they all sought to extinguish.

While the posh colonials unveil their cruelty, Danny Huston's Arthur Burns is allowed to reveal the qualities that are excluded from his reputation. He is repeatedly classified as an animal, as a dog by numerous characters in the film. He is viewed as subhuman by those who pursue him, depicted as a beast whose only just outcome is death because he cannot and does not deserve to be tamed. And he is indeed a terrible person. His guilt in the rape and murder is never questioned nor exonerated. But he also embodies other characteristics that the British have determined as worthy of celebration. He is a sadistic man, but his savagery constantly butts heads with the fact that he is by far the most intelligent character in the film. He is a man who essentially lives in a cave, but books can be seen scattered across the rocks which he sleeps on. As he drives a knife through a man's heart, he recites poetry about love. Despite being the most violent character, Arthur is also the most loving. He is almost brought to tears when Charlie tells him (or rather lies to him) that Mikey has fallen in love. When a member of Arthur's gang asks him if they are all misanthropes, Arthur responds with "Good lord no, we're a family". Arthur's lust for blood is only rivaled by the love he has for his brothers and friends. That is not to say that it justifies or rationalizes Arthur's actions, of course it does not. But he is the embodiment of a colonialist philosophy that butts heads with itself. He is the type of person that Stanley and Fletcher want to exterminate, but he also possesses so many of the values that they wish to impart.

It is not clear why the English have settled this remote region of the Australian Outback other than the mindless pursuit to enforce Captain Stanley's thesis of "civilizing this land". It is not explained why the Burns brothers are there either, but at least they are there to accept the Outback as their home and embrace the indigenous residents of it as their community. The British are there to impose their idea of righteousness onto communities who in many ways are made up of people similar to their own. They already possess the intelligence, kindheartedness, and family values that Fletcher believes his community monopolizes, while the settlers use their perceived moral superiority to justify the same type of violence that they are trying to expunge. The Proposition boils down the conundrum of colonization into a vessel of hate, where buzzwords like "civil" mask the racial and ethnic prejudices that are the true motive behind the expansion. While the stated goal is to establish civilized society, the only thing that gets preserved is the circular nature of violence.