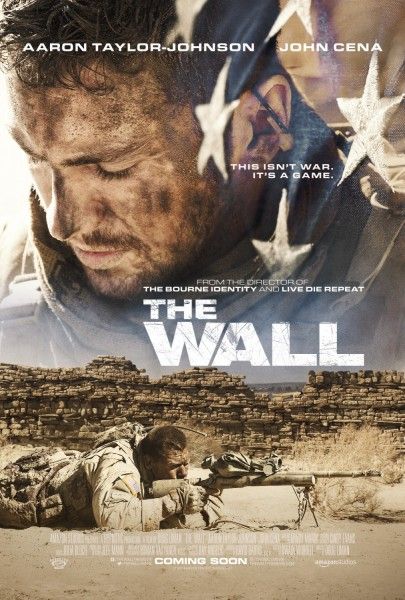

It’s easy to understand why a director with roots in the indie world who’s become a major big-budget adventure director like Doug Liman would want to make a small, intimate film before making the next big Tom Cruise movie. It’s also easy to understand why Aaron Taylor-Johnson would want to prove that he can carry an entire film on his shoulders. It’s easy to understand why both men would want to make something like The Wall: a war film where two American soldiers get pinned down by enemy sniper fire and are unable to call for retrieval on their radios and must be crafty about their escape. Something like The Wall has the potential to be an exercise in tension and/or an intense character study in which our involvement in modern warfare comes under a microscope through the trials of a character we connect with.

While it’s easy to understand why Liman and Taylor-Johnson would take on The Wall as a personal exercise, I don’t really understand who the resulting movie is actually for. By the end of its runtime it’s essentially become Iraqi Sniper, a portrait of an unseen Iraqi sniper who’s really, really good at killing enemy combatants. No, that doesn’t mean that Taylor-Johnson’s character dies at the end, don’t worry, that’s not a spoiler. It means that in order to make a 90-minute runtime, Dwain Worrell’s script introduces the Iraqi sniper on Taylor-Johnson’s radio in order for the Iraqi man to ask questions about Taylor-Johnson’s Isaac and why Isaac has returned for an additional tour in 2007 when most American soldiers have long left. And the sniper (voiced by Laith Nakli) will get to reminisce about all the GI Joes he’s killed. Juba, the unseen sniper, really wants to know about Isaac for reasons that transparently sound like board-room story whispers: we need our audience to know that our Isaac re-upped for personally justifiable reasons and, get this!, if the Iraqi sniper quotes Edgar Allen Poe, we’ll also have an eccentric Western-educated killer!

The Wall opens with Isaac and Matthews (John Cena), discussing their options, after they’ve posted themselves above an oil line execution for almost an entire night and day. Eventually they decide to get a closer look because no Iraqi sniper would’ve kept their post that long because they don’t have the rigorous training and breakdown of personal willpower that American soldiers do, that’s what Matthews deducts. Of course, that is proven incorrect when Matthews is shot in order to draw Isaac out to his defense. Then Isaac’s radio antenna is shot and his leg is shattered, forcing him to dive behind a crumbling wall to gather himself and attempt to somehow rescue his fallen mate and make contact with their base. But their assailant has a cat and mouse game in mind.

For Liman, there’s symbolism in his contained surroundings. The titular wall is a structure that serves no purpose to its current filling station surroundings; it’s not keeping anyone out. Luba informs us, after sliding into Isaac’s radio channel (because he’s the only signal nearby) that the crumbled structure used to be a schoolhouse. It was bombed and its pitiful coverage is all that stands between Isaac and another bullet. And the patient sniper who outlasted his American counterparts in waiting for his prey to be lured into his scope? He’s situated in an area that’s concealed due to excessive business waste. The circular repetition of what creates great soldiers in this unofficial war—Western business and revenge for destruction—is handled with a bit more subtlety than the slogan of Liman's last (and great) film: live, die, repeat. But the interaction between Isaac and Luba creates a diagram that's inescapable.

American audiences that make war movies a box office hit generally go to see how they view their military—better in stature or instilling a strength of character that allows them to outlast and outwit the enemy—reinforced.The Wall desires to show the other side of that scope, but in not showing Luba and only the Americans, the narrative becomes uncomfortable. The audience is a pawn in this game. The hidden, intelligent and well-trained assassin on the other side seems to only remain hidden because the filmmakers are aware that audiences don't want to see Americans shot at unless they're able to make them heroic. But the resulting film doesn't pull us close enough to Isaac or Matthews to be a revealing experience of showing heroism outside of national identity and having a family. And for the globally compassionate audience who feels conflicted or concerned about the motivation behind modern military encampments, Luba and Isaac's interactions don't provide any insights beyond the what came first, the American intrusion or the Middle Eastern terrorist, question.

As an exercise of small-scale filmmaking, Liman uses compact camerawork to make every inch of the scenario in The Wall felt. One miscalculation by a matter of inches could mean death. And Taylor-Johnson holds our attention—even though the performance is mostly body horror wails of pain and grunts of movement. But Liman never forces the story nor his actor to delve deeper into the psychological terror of the situation. The indie director of Swingers and Go has used his post-Edge of Tomorrow downtime to box himself into a cat-and-mouse sub-genre without identifying what psychological horror he'd like to explore. The crumbling wall doesn't just represent a bombed schoolhouse, it also serves as a metaphor that the set-up of this movie is so skeletal it can only barely hide a movie behind it.

Rating: C

The Wall opens in select theaters May 12.