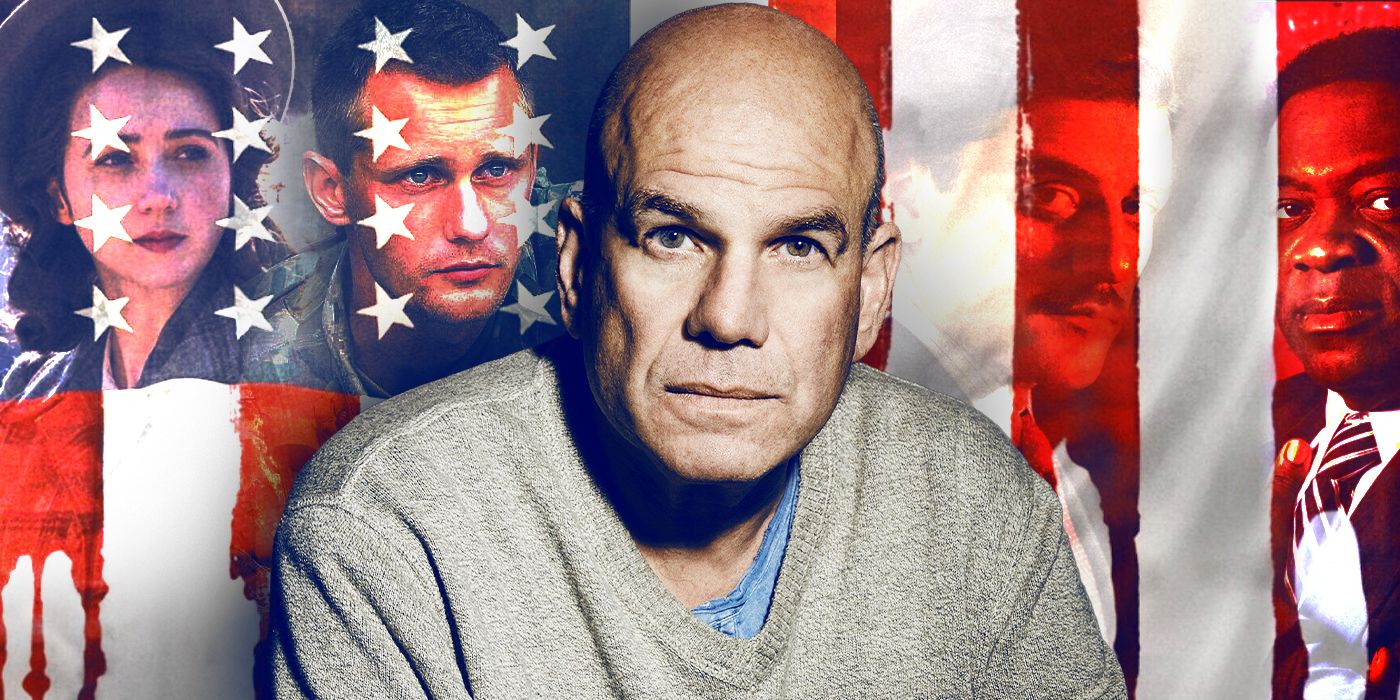

David Simon, the beloved creator of The Wire, has joined the picket lines of the Writers Guild of America strike to defend the future of Hollywood. During an interview with More Perfect Union, Simon perfectly summarized the reasons for the strike as only a storytelling master can do, explaining the complex legal battle between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers in terms anyone can understand.

Last March, the WGA began a round of negotiations with the AMPTP to ensure Hollywood writers could get fair wages for all their hard work. Unfortunately, the AMPTP refused to negotiate, eventually leading to the WGA approving a nationwide strike. The strike has already impacted dozens of TV shows and movies, and if a deal is not reached soon, the Hollywood machine might be completely frozen in the next few months. Of course, from the outside, people wonder why writers are on strike and when their favorite show will return to production. Simon perfectly explains the situation by comparing the current work contracts offered to writers to what he got in the first TV show he ever worked on, Homicide: Life on the Street. As Simon remembers:

“Look, when I came into the business – the ‘Homicide’ season was the production, pre-production, production, post – I had 30 weeks on. Sometimes more, depending on the episodes. You can make a living off that. And then the other 20 weeks when you're not working, ok. You know, we were paid at a decent enough rate. You hold on to your money, you wait for this next season, or if the show doesn't get picked up, you find another. You always had to find the gig, but the gig would pay you enough to make it plausible for you to afford a mortgage or for health insurance. Now they'll start a mini room and they'll say ‘Here's three weeks of salary. And by the way, we're not guaranteeing that you'll get a script for a script fee. Just a three week salary. Just come and give us your ideas. We may make the show, we may hire you. We may not hire you and then go find another gig or we're not sure we're going to order the show. Let's see if we order the show. But while we're deciding don't take another job. We have you under contract for three weeks of work and you got to survive and you got to raise a family with that. It's crazy.”

What Does the WGA Want with the Strike?

During the interview, Simon also underlined how the business of television has changed with the emergence of streaming platforms and the increased focus on shorter seasons. According to Simon, new contracts should consider these changes, because:

“For example, when I worked on ‘Homicide,’ there were 22 episodes. So writers had a chance to get more work. We were on staff for longer. The episodes were all – for lack of a better word – episodic, meaning they were all connected into one major story. You couldn't do that with 22. So you couldn't write them all in advance of filming a season. So basically, they needed writers to hang around and make that show work. As the broadcast model has faded, with shorter seasons – with episodes that require more production quality or comprehensive story work earlier on –, they've been able to pay writers out fast. They'll make a pre-production room of eight or nine or 10 weeks paid, demand everybody's scripts in advance, and then leave a showrunner alone or maybe with a minimum of assistance on set to make all the changes that need to be made. Every time you lose a location or every time you see something's not working with an actor, or every time you need to cut time. Shows, you don't finish writing when you hand in the first draft of the script or even the shooting script. So you're always writing. And yet they found a way to make showrunners do double the work and to cut other writers, story editors and staff writers out of almost all of the paid salary. Well, that's resulted in guys not being able to make their mortgage, especially the younger writers.”

While the way television is produced has changed, what remains constant is the need for writers to stay on set to ensure the quality of our favorite shows. Many people might think a writer’s work ends when they deliver the scripts during pre-productions, but as Simon explains:

“Writing happens all the way through production and it happens in post-production until we do the last ADR and write the last bridging material where we've cut scenes and gotten down in time. I need writers. And you could ask me as a showrunner and say, ‘well, you're a writer.’ I'm also managing the entire concept of the show. I'm cutting film. I'm dealing with contracts for next year. Showrunning has a lot of facets. And if you're saying, ‘oh, by the way, do all the writing and don't have a writing staff,’ you're basically saying, ‘ok, be management, be the producer part of your title, and also do the writing.’ What writers are saying here is, ‘look, that's destructive to the core of a writing staff, to maintaining a writing staff that can sustain a show going forward, but it's also an incredible burden.’ Meanwhile, the writers who are doing this for a living are being told, ‘we don't need you on set. We don't need you doing any of this work. We'll get it from the showrunner.’ So they're down to 8, 10 weeks of work. They can't make a living in a year. They're down to a gig economy and they're also not learning all of the skillsets that are going to make them into better writers and better producers. So you're not growing the future.”

Writers are indeed essential to the making of good television. So, keeping a writer’s room is also an important tool to teach the next generation of writers how to handle the many aspects of a TV show’s production. Simon brilliantly sums up this need by saying:

“The truth about storytelling and film form is that even the people who are not visually trained, i.e. the writers, understand the story better than anybody, better than the actors. Actors understand their characters beautifully, better than the writers. Directors understand shots better than the writers. But it's the writers who understand the story. And it's why when you give over a comprehensive long-form story, like in TV, they put the writer in charge. Because when you get to episode 11, you remember everything you set up in episode one, and that's a long haul. And if you're not training people to conceive of that whole, you're not preparing for the future.”

Big Studios’ Mergers Have Led to Irrational Cut-Costing

During the interview, Simon also discussed how big studios have undergone several changes in the past few years. For instance, Disney acquired Fox, and Warner Bros. merged with Discovery. While the union of giant companies under the same banner might seem like a good business strategy, the mergers could only be done by acquiring a lot of debt, which these companies are trying to compensate for by cutting costs in the short term instead of thinking about the future. Simon once again gets straight to the point by saying:

”There's a certain impulse that says, ‘I just got to cut costs. I don't have to grow the business. I don't have, I don't have to make this thing more creative. I don't have to expand the subscriber base and convince more people to take my product. I just got to cut costs.’ It's the simplest, most brutal way. But what it does is mortgage the future. And if you're thinking about what makes TV and film, and what has made it, and what will make it in the future, it's the story, it's narrative. And that begins with the writers.”

AI Is a Tool, Not a Writer Replacement

Simon also discussed the WGA’s propositions to prevent studios from using AI to write movies and TV shows. As Simon puts it, “Anything like a thesaurus or a dictionary or a book of quotable quotes can go on a writer's shelf and be a tool.” However, tools like AI cannot replace a writer because they are not capable of creativity. For Simon, AI writing “is a derivative form. You're feeding all the crap into a computer and saying, ‘Give me a generically sound cop show like every other stinking cop show done, or a medical show, or law show. And that derivative work is never going to break ground.” Simon goes even further, by comparing AI writing to copying a work of art. As the storyteller elucidates:

“[AI writing] is basically like buying a Xerox copy of a print and putting it on your wall. You know, that's ‘Starry Night,’ that's ‘Guernica,’ but nobody is going to really look at it with the same hard look that they would give an actual painting. And so I don't mind the idea of it [AI] as a toolbox for writers. But don't have a studio telling me, ‘look, we ran it through the algorithm and this is our favorite AI and this will make a cop show that will maximize our viewership.’ Because, in the short term, you might fool some people into watching 10 episodes of crap. But over time, the viewership for that is going to diminish. There's always been a certain amount of derivative crap on television. There always will be. But there was also the running room to create something new.”

While Simon is a successful Hollywood writer who doesn’t need to worry about how much money he makes, he’s still on the picket line defending the rights of the younger generation. Simon concludes:

“This is a strike for the younger writers, you know? I'm not paid by the episode, and I'm not paid on a weekly rate, and I have a development deal – it may be canceled in five weeks because of the strike. But, you know, I had my run and it's fine. The younger people coming up, they deserve a career. And some of them are great writers and great writers to be. And they deserve a job and this strike is for them.”

Collider will keep reporting all the news from the WGA’s picket lines for the duration of the strike. Check out Simon’s full interview below.