A good horror film isn’t terribly easy to create. Sure, you can make audiences jump with loud noises or the sudden appearance of a character, or you can make them long to find out the rest of the mythology behind a particular bad guy/book/object of questionable mystic qualities before all curiosity falls away once it’s revealed. But it’s tough to craft something in the genre that stays with people once they’ve left the theater. With writer/director Robert Eggers’ feature film debut, The Witch, however, that rare, memorable and affecting horror film has arisen. Opting for dread and mood over jump scares or deep mythology, Eggers delivers a seriously terrifying and deeply unsettling “New England folktale” set in colonial America that is intensely disturbing and wholly unforgettable.

Set in 1630 New England, a generation before the Salem witch trials, the film revolves around a small family that has been excommunicated from its plantation due to father William’s (Ralph Ineson) outspoken objections to what he sees as the community’s lax religious principles. William welcomes the chance to leave the plantation and practice his strict adherence to the Lord on his own, moving his family to a remote cabin near the foreboding woods.

Early in the story, daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy)—verging on becoming a woman herself—is playing peek-a-boo with the family’s baby near the treeline when, all of a sudden, she opens her eyes to see the boy is gone, with no trace of where he went. The audience is then introduced to a cloaked figure running with the baby through the woods—the titular witch—and what happens next is unspeakable. Suffice it to say, Eggers conjures the film's physical antagonist in such a way that you’re left both wanting to see more of her and never wanting to see the character again.

What follows is the crux of the film’s conflict: the family struggles with the disappearance of the child while attempting to maintain their faith in God in light of such a tragedy. Moreover, things keep getting worse, as their harvest of corn goes bust and, without the safety of the plantation, the family is in danger of starving to death during the winter.

The faith of the individual family members—which also includes mother Katherine (Kate Dickie), pre-teen son Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), and two young, rambunctious twins Jonas (Lucas Dawson) and Mercy (Ellie Grainger)—alternatively wavers and stays strong as they question original sin, the afterlife fate of the young baby, and whether they themselves have been redeemed in the eyes of God. Is it possible to go to heaven if you’ve sinned? Can we know for sure that God forgives? What does it mean to invite sin into your life, and what do those consequences look like? These questions are pondered by the individuals of the family, namely Thomasin, William, and Caleb, and begin to weigh on their hearts, turning their tension and doubt on each other. Someone must be to blame for their poor fortune, and if not God, it’s surely one of them.

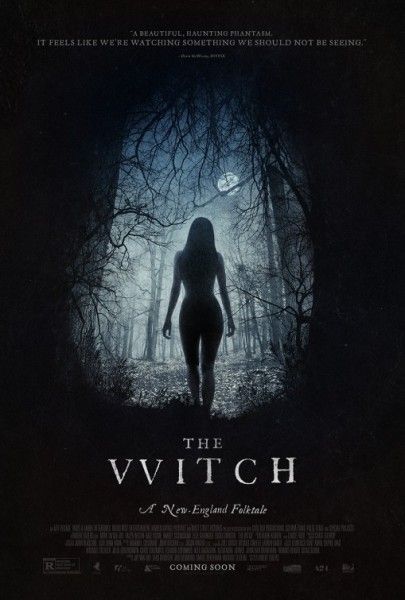

And throughout all of this, there’s the encroaching dread of the witch, which the family may or may not believe exists. Instead of crafting a villain whose face the audience comes to see as familiar and iconic, Eggers knows that the true power in this kind of film is what you don’t show. The audience is constantly left in question of just exactly what the witch looks like, and at the same time the brief glances we do get are absolutely chilling. This tease of just enough but not too much is executed to perfection, which not only increases the tension surrounding the witch herself, but keeps the story’s main focus on the family. The key to The Witch is that Eggers deals in dread, not scares. Aided by a striking score from Mark Korven that owes a debt to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (many times a shot will linger just a little too long as the music grows louder and louder, becoming more and more terrifying), the audience is constantly watching in trepidation, not sure where the film will go next. Jarin Blaschke’s bleak yet hauntingly beautiful cinematography adds yet another layer to the film’s atmosphere, fully engrossing the audience into the secluded, colonial setting. And the performances, especially young Taylor-Joy, are quite effective, selling the sense of isolation, regret, and deep-seated tension amongst one another.

The movie does deflate a little bit in the middle section, which drags a tad as dread gives way to despair and the inner turmoil of the remaining family becomes somewhat monotonous. For a moment it seems like The Witch is poised to switch its focus to becoming a sort of prequel to the Salem witch trials (some of the dialogue was pulled straight from Salem-era journals), but then Eggers delivers a third act that, quite simply, scared the living hell out of me and will be ingrained in my mind for a very long time. Brain, meet nightmare fuel. While the horror genre has never really lost its prevalence over the years, it feels like a lot of “scary” movies these days are simply going through the motions, offering up the cinematic equivalent of junk food—it may taste good in the moment, but it’s not necessarily fulfilling or all that memorable. The Witch is not only an incredibly well-crafted horror film, it’s a good movie period. Eggers announces himself as a talented filmmaker to watch, with a knack for blending genre elements with larger, more thoughtful questions, which in the case of The Witch consider sin and inherent goodness. That the film will most likely find you wanting to watch with one hand covering your face is just a bonus.

Rating: B+