2017 was a big year for superhero films. Wonder Woman burst onto the stage with the first female-led superhero film since the genre’s resurgence, with its title heroine teaming up with her fellow DC heroes in the long overdue (albeit very messy) Justice League a few months later, while over at Marvel, James Gunn and Taika Waititi, with Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 and Thor: Ragnarok, respectively, had delivered two of the greatest entries in the MCU that managed to retain the personal touch that many of their compatriots lack. However, towering above them all was Logan, Hugh Jackman’s swansong for the claw-wielding mutant whom he had portrayed for seventeen years. The film’s intimate take on the overblown genre made for a refreshing change of pace from such films, with its R-rated tone allowing for a more contemplative pace, while also allowing for an increased use of violence to underline the pain of its title character. Its success earned it an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay, the only live-action superhero film to be recognized for its writing. It was a nomination well-earned, and as the years continue on and the glut of comic-book films continues to grow, there is no doubt that Logan will go down as one of its crowning achievements.

In fact, Logan was so good that it’s easy to forget the film that preceded it, 2013’s wildly underrated The Wolverine. While first impressions may give the apprehension of this being just another superhero film in a sea of thousands, closer inspection reveals a film of considerable depth that shares more than just its main character with its sequel. Both films featured James Mangold and Scott Frank in the roles of director and writer, respectively, and in hindsight, The Wolverine feels like the first attempt at many of the concepts they would later perfect with Logan. The emphasis on a smaller-scale story featuring a weakened Wolverine dealing with the consequences of his actions both past and present, alongside a strong focus on the setting that imbues itself into every aspect of the film, is a description that would fit either film. However, it’s clear that the requirement to produce a commercial blockbuster perfect for the summer movie season led to much of The Wolverine’s potential being left on the wayside, most evidently in the film’s infamous final act that feels like it belongs in an entirely different film. The Wolverine is a film suffering from an identity crisis, and while the success of Logan arguably renders it insignificant, it’s interesting to see how it planted the seeds that would grow into something spectacular.

The plot of The Wolverine (taking inspiration from Chris Claremont and Frank Miller’s acclaimed 1982 limited series) follows X-Men: The Last Stand, which saw Logan being forced to kill Jean Grey (Famke Janssen) to save the world. Logan now lives as an outcast in the wilderness of Canada, only to be tracked down by Yukio (Rila Fukushima), an assassin who works for an old acquittance of his called Ichirō (Haruhiko Yamanouchi). Logan agrees to accompany her to pay his respects to Ichirō before he dies, but once there, he finds himself confronted with a difficult choice: transfer his healing abilities to Ichirō and finally become a mortal man, or continue to spend the rest of his days ostracized from the very world he had tried to protect. Logan refuses his proposal, but after an attack by Yakuza gangsters at Ichirō’s funeral that leaves him closer to death than he had been for centuries, it becomes clear that he never had a choice in the matter.

Without question, The Wolverine’s greatest strength comes from its incredible use of setting. It’s a philosophy that Mangold would also employ in Logan, where each film's central location is infused into every aspect of its narrative and presentation. Qualities that are commonly associated with Japan—the sanctity of family, the duties one is beholden to based upon their position within society—form the core tenets of The Wolverine’s story. Its many scenes of familial conflict interspersed with action sequences featuring katana-wielding samurai give the impression of a contemporary take on an Akira Kurosawa film, with Logan himself adhering to the heroic outsider archetype that he utilized in many films. Iconic Japanese iconography like love hotels, bullet trains, and shoin-zukuri style architecture become central locations that fundamentally alter how the story is conveyed, all shot with a precise framing that calls back to some of Japan’s most acclaimed directors. This ethos would prove to be Logan’s greatest strength too, where Japan was switched out for the Old West in a story that felt like a modern-day take on Shane or Unforgiven. It’s refreshing to see a superhero film that treats the setting as an integral part of the experience rather than just the wallpaper, and it’s no surprise that Mangold would return to this idea after using it so brilliantly in The Wolverine.

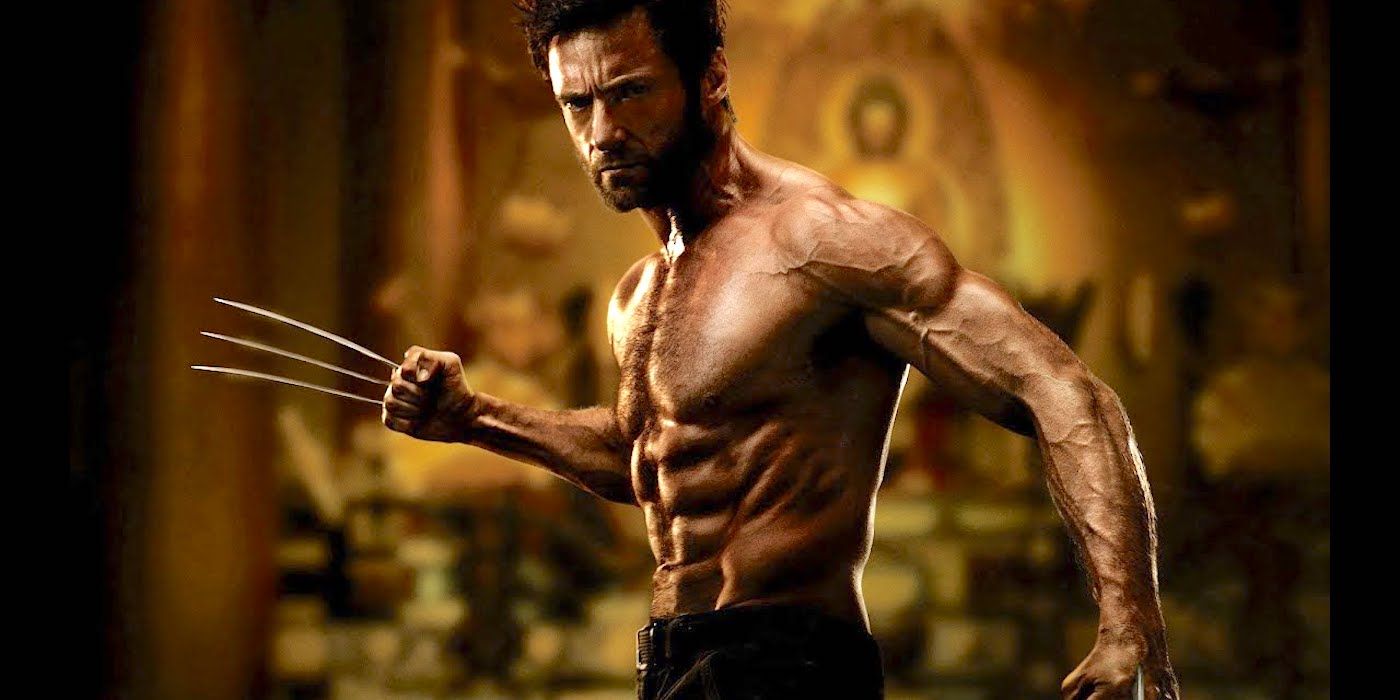

The concept of including a weakened Logan is also something he would reuse. It allows him to avoid the recurring issue regarding how invulnerable most superheroes are, in turn eliminating any tension when we know they’re going to walk out of every situation that comes their way. Wolverine is particularly guilty of this, and watching him claw his way through hordes of bad guys only remains compelling for so long. The Wolverine avoids this issue. Suddenly our hero can no longer jump headfirst into any obstacle on the assumption that he’ll make it out alive, opening the door for a more thoughtful approach to action. The concept of a fight sequence atop a speeding bullet train might sound like exactly the sort of ludicrous display of mayhem that the genre is known for, but in practice, there’s a tactical element to it that elevates it above the absurdity that it could have been. Logan would also take this approach to action, allowing Mangold to craft sequences that seamlessly integrate with the surrounding film rather than feeling like an entirely disparate element.

One of the most notable aspects of Logan was its R-rating, allowing for scenes of graphic violence that highlighted just how damaging (both physically and mentally) Wolverine’s powers could be. It seems Mangold already had this idea in mind when he made The Wolverine, as the home release included an unrated cut that preempted the level of gore seen in Logan. However, it’s clear that The Wolverine was not built with this rating in mind, resulting in most of its gory images being very blink-and-you’ll-miss-it. Thankfully, Logan would not repeat this mistake, and used its R-rating for greater effect than the occasional CGI blood spurt that feels tacked on after the fact.

The Wolverine also places more focus on its main character, allowing for a mature examination of the nature of superheroes that would continue with Logan. Logan spends much of the film’s first act viewing his abilities as a curse, condemned to outlive everyone he cares about without even so much as a scar as proof of all the torment he’s suffered through. When we first meet him, living in the forests of the Yukon and picking fights at the local bar, he’s almost 200 years old and harboring an unspoken wish for the thing everyone else spends their whole life avoiding. It’s only when faced with his own mortality that he realizes the good that his powers can bring. Not many people could sustain the blast of an atomic bomb (as seen when he saves Ichirō’s life during the film’s opening scene in 1945 Nagasaki), and his realization of what The Wolverine means and the good it could bring to the world is an interesting idea. It’s a shame that he’s back to his usual brooding self by the time we catch up to him in Logan (where he undergoes basically the same arc).

But despite these qualities, The Wolverine still pales next to its sequel. The final battle sees Logan fighting the Silver Samurai, a giant CGI suit made from adamantium and being piloted by a disappointing plot twist. When coupled with Logan’s rejuvenated healing powers and the presence of a snake lady who spends the whole fight spitting poison, it feels like a finale to a different film. Specifically, it feels like a finale to a typical superhero film, something The Wolverine had avoided up to this point. The ending also sees Mangold falling back on the old clichés, opting for the usual ‘the adventure continues" trope where our main character ends the film in basically the same place as he started it, preventing any substantial growth in order to not prove troublesome for the next film.

Compare this to Logan, whose final act served as a natural progression of what had come before rather than feeling like a leftover from a previous script. When Logan regains his full strength, it’s not because he cut himself open to remove a robotic parasite from his heart several scenes earlier, but because he injects himself with an experimental drug whose aftereffects lead directly to his death minutes later. And that’s not even mentioning its closing scene, which manages to use the most basic gestures to create the most powerful final shot in a superhero film. It’s clear that Mangold heard the criticisms about the previous film’s climax and committed to improve upon it for Logan, and in doing so, he managed to not only avoid repeating The Wolverine’s most fatal flaw, but also created one of the greatest endings in the history of the genre. Quite a turnaround.

There’s a moment in The Wolverine’s second act that encapsulates the whole film. While on the run with Ichirō's granddaughter Mariko (Tao Okamoto), Logan decides to help the residents of Nagasaki by chopping down a fallen tree that has blocked a road. It lasts for a matter of seconds, but that Mangold decided to include such a moment amongst the cacophony of noise and action says a lot about his approach to the material. It’s reminiscent of a similar scene in Logan, where our hero takes the time to fix a broken water pump while residing on a farm. Both scenes share an identical function – providing a reprieve from the larger story that reinforces their commitment to existing in a more grounded world – but Logan’s is an improvement in every way. It provides depth to the owner of the farm (an important side character at this stage of the film), introduces a group of enforcers who prove essential in a subsequent action scene, and also stays onscreen for longer than twenty seconds. It encapsulates the notion of The Wolverine as a first draft, improving upon what works here in Logan.

While it is far from perfect, The Wolverine still stands as one of the most exciting superhero films in recent years. Its smaller approach and excellent use of setting put it firmly in the upper echelon of X-Men films, and it’s a miracle that Mangold and company were given a second chance to refine their mentality in time for the next film. Logan is one of the best superhero films ever made, but let’s not forget the film that paved the way for its existence.