Film buffs will forever give director Thomas Vinterberg a special place in movie history for co-creating the minimalist 90s film movement Dogme 95 along with professional provocateur Lars Von Trier. Vinterberg made the first and best Dogme movie The Celebration. That incendiary tale of secret child abuse in a wealthy family earned him a Palm D’or in 1998 and launched his career. Since then he’s produced some interesting films like It’s All About Love and Dear Wendy, but never one that made quite the same impact. Well, until now anyways.

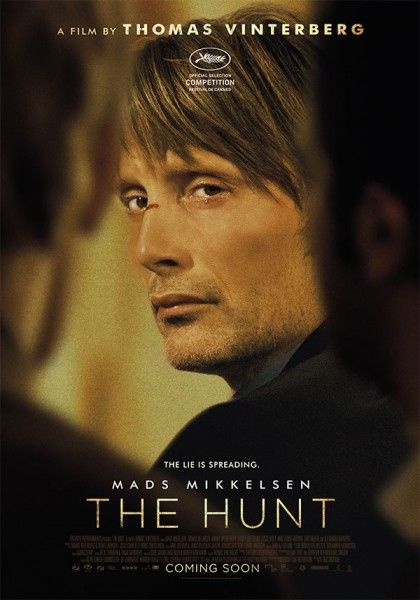

This year Vinterberg returns to TIFF with another film hinging child abuse in The Hunt. Madds Mikkelsen stars (in a role that already earned him a Best Actor statue in Cannes) as Lucas, a kindly kindergarten teacher who is accused of abusing one of his student Klara. The town instantly turns on Lucas en mass, doling out psychological and physical abuse. The only thing is that Mikkelsen is completely innocent of the accusations and can’t seem to prove it, making the unfortunate witch hunt painful to watch. It’s one of the most powerful and unforgettable films of not just the festival, but inevitably the year as a whole. We got a chance to chat with the director about his latest film at this during this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. Hit the jump for more.

Collider: So, where did this start for you? Any connection to The Celebration?

Thomas Vinterberg: There was a psychiatrist living on my street and I didn’t know him but he knocked on my door and said, “You did The Celebration? There is another film that you have to do because I have a lot of these cases on my desk.” I waited a few years before I read it. I shelved it and then when I needed a psychiatrist eight years later I took it down and read it. I thought, “wow this potentially very strong and in a way kind of important.” I’m not a preacher, I’m not out to inform the world about moral issues. But I thought in a way it was interesting to make an antithesis to a film I did 13 years ago.

So it was an actual cases and not a script that you got at first?

Vinterberg: It was initially one case and then I read about a lot of them. There are many of these cases, even here in the States. Of course you never know if they are innocent, but at least some of them are.

Did you write it with Madds Mikkelsen in mind and what made you think it was right for Lucas?

Vinterberg: I did not. It’s not like that with Madds. You need a script first to attach him. But normally I would want to write with an actor in mind. So, when Madds came on board I changed quite a few things in the character in collaboration with him. He changed from being a Robert DeNiro in The Deer Hunter man of few words tough guy. I thought well Madds is already a portion of that. He’s such a strong good looking man and a hero already that I thought let’s make him a little bit more of a Scandinavian, humbled, slightly castrated, good hearted man. A good Christian. Then let it develop from there. Let him exist in this sort of limbo, trapped by his own civilized behavior until the head butt, then he transcends into the world of movie men.

Did his background in playing unsavory characters play a role in the casting, to play off that image and make him an innocent man?

Vinterberg: Well, famous actors such as him come with a story that we know about them. I played with that, but not in the sense of him being a villain, but that’s interesting that you bring it up. I played more with the fact that he’s always very manly and very tough and very strong. I found it interesting to switch that around. But him as a villain, to be honest I didn’t see all of those movies. I saw some of them. But I’ve seen everything he did before in Denmark. He did some great movies.

What interested you about playing with the irony of Lucas being the most moral man in his community despite being accused of the most terrible possible crime?

Vinterberg: Well, that’s the mathematics of drama. You want to put your character in the most unjust situation and have him fight out. He is a very just man, which is why it’s so terrible what happens to him.

What was your motivation behind presenting the people in the town as being so vitriolic and close-minded the second they hear of his crimes?

Vinterberg: Well, we tried also to define and defend all the characters. We think they do as good as they can. They of course react irrationally. But who wouldn’t in that situation or at least a lot of people would. We tried to totally defend each one of their steps and actions. I see them all as good-hearted people, but they have this splinter in them. Like a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of evil spreading like a virus. We considered the thought a virus and the spoken word. So maybe they react too fast, maybe they are too easily convinced. That was a delicate thing to balance. But I’m not sure. I mean, if you look at the cases it was much worse.

How so?

Vinterberg: People were judged so quickly. In one case that I read about from Norway, I think 40 something people ended up in prison including the local sheriff. What fascinated me, was that you’d have 18 children coming up with the same precise descriptions of men in monk costumes, being forced to eat feces, the colors of the walls. All sorts of details that were all identical between the kids and then they’d go check the house and there’s no basement, like in our movie. So this collective fantasy gets so specific and so detailed on the playground. This film is a much more civilized version of what actually happens. We made it watchable. We made the airplane version of real life.

I really appreciated the interrogation scenes with Klara where the adults are almost putting words in her mouth—

Vinterberg: Which is almost directly from a real transcript. Just toned down. We really had to redit that scene many times. It was much, much worse in the actual story. But then again it was the 90s and it has to be said that they have improved their methods. This was a police investigation initially and I thought it would be even more interesting to give the man no name and have him come from an unknown organization.

I thought the actress who played Klara was incredible

Vinterberg: Yeah she’s good.

I was curious how you worked with her on some of those scenes? Did you explain everything to her because it’s such delicate material for such a young child.

Vinterberg: Well, it is Denmark. We’re more liberal about these things. We talk about these things. But then again, there are limits. We didn’t want to harm her. So we had a very thorough conversation with her parents. You know, it was sensible in the sense that she doesn’t know what it is. She knew that it was something bad and she knew that she was lying. She knew that it had sexual characteristics, but then again she doesn’t know what sexuality is. And she didn’t really care. She wanted to play with her Lego and dolls in the corner. We explained what was going on, but she didn’t really care. What she enjoyed was the sport of being an actress. “I want to do this really well so that they all clap again.” That’s what she was thinking and that’s what we did. She was really good.

Were there any instances where you would shoot half of a scene with her and half with the other actors saying or doing something without her there to avoid any uncomfortable situations?

Vinterberg: Yeah, there was some of that with the sexual stuff that the guys show her. We didn’t want to actually show her that. Maybe there were other examples, I don’t remember. It’s an interesting question because it makes me think about what the film is about in a sense. There is this increasing fear and overprotection of the little ones, which I find a bit sad. There’s a loss of innocence. Especially from my childhood. I grew up in a hippy commune with naked people and genitals all over. All these things are gone now. There was no harm, no one took advantage of me. But now you can’t even have another person’s child on your lap if you’re a guy. You can’t even embrace them or hug them if they cry. No physical contact, which I find disturbing. I find it a little hysterical. So when you ask that question, we tried to be straight with her and not hysterical, but of course do no harm to her, We had to find a balance.

And it was nice that her character isn’t some completely innocent golden child either.

Vinterberg: No, she lies. Some people have been provoked by that. There’s this convention that children don’t lie. Well, sometimes they do and you can’t judge that. Most of the time they do it to satisfy the grownups or get some attention. There’s always a good reason. The problem is that a lot of these kids end up suffering as much as those who have been abused. This whole scenario around when accusations are made makes them believe that it happen very fast. It only takes a couple of weeks with a child. And then they end up growing up as victims and have just as much trouble even though nothing happened. They are always the victims in this game.

Since I have you here there’s something I have to ask you about. Last year at this film festival I saw Melancholia, which I loved. But I did find the first half of the movie remarkably similar to The Celebration. Since you are friends with Lars Von Trier, I wondered if that was something you two had ever discussed.

Vinterberg: (laughs) Well, actually he called me and said, “I stole your film.” Which he did, it was just not as good. The second half I thought was brilliant, but that first half was very close, yes.

And how do you feel about the legacy of the Dogme movement all these years later. It’s amazing how fare it’s reached over the years with Paul Greengrass’ Bourne movies even putting that aesthetic into Hollywood action blockbusters.

Vinterberg: Well, I’m very proud of what we did and I do think it provided quite a bit of inspiration for many directors, including Greengrass. I think it was important to do at that time. It put a mirror up against conventional filmmaking and said, “we can be different.” I think it removed a lot of layers between the audience and the story and the actors. In that respect it was great. For us in the middle of it, it was very quickly over. For me it was a problem because I did The Celebration and I was young. I realized that I couldn’t go farther down that road. That was the best that I could do in that direction, which left me floating in the air. I didn’t know where I would go next. But obviously people were inspired by it.

Do you still use any of the techniques from Dogme like the improvisation?

Vinterberg: I do. Sometimes. For my next film I will use much more improvisation. I’m actually going to make a film about the commune I grew up in that I mentioned earlier. I think we’ll have to do some improvisations there.