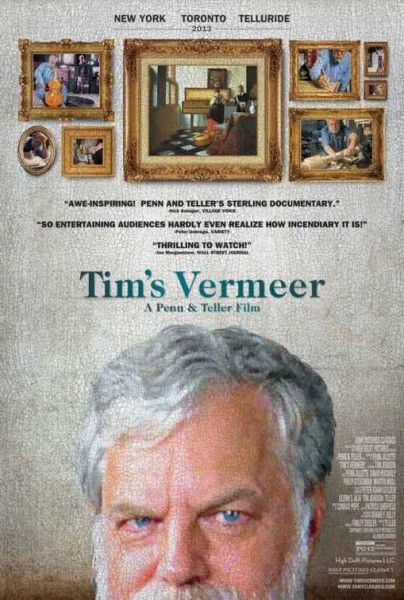

Opening January 31st, Penn & Teller’s entertaining documentary, Tim’s Vermeer, centers on Tim Jenison, a Texas based inventor who attempts to solve one of the most intriguing mysteries in all art: how did the great 17th century Dutch artist, Johannes Vermeer, capture light in his paintings with such photographic quality 150 years before the invention of photography. Determined to find out, Jenison embarks on an epic research adventure that takes him to Delft, Holland where Vermeer painted his masterpieces, the North Coast of Yorkshire to visit artist David Hockney, and London to view Vermeer’s The Music Lesson in the Queen’s Collection at Buckingham Palace.

In an exclusive interview, Jenison talked about how the idea for the project first came to him, how a casual conversation with his longtime friend Penn sparked the idea for a film, why he loves the power of ideas and inventions and considers Vermeer a fellow geek, what happened when he realized the use of camera obscura alone was not sufficient to capture the range of color and tones that are the heart and soul of Vermeer’s paintings, how he duplicated Vermeer’s tools and materials to recreate The Music Lesson and test his theory, his excitement at sharing his findings with Hockney, and his plans to write a book. Read the full interview after the jump.

Collider: Can you talk about the genesis of this project and how it came together?

TIM JENISON: It was an idea I had in the bathtub. I’d been looking at the Vermeers. I’m not a big art buff, but I’m a video engineer. That’s one of my hats. When I looked at the Vermeers, there was something obviously different about them and I realized what it was. The way Vermeer painted those white walls is not the way anybody else painted those white walls. They painted a white wall. Vermeer painted a wall that went from almost white to almost black and that’s the way a camera records the scene. But our eyeballs don’t work that way. It’s literally the retinas of our eyes. I know this from being a video guy. When we look at a wall, (referring to the wall in the room where our interview takes place) this looks like beige to us, but it’s actually a zillion shades from almost black down there in the corner to really, really bright right there by the window. But it looks beige. And so, I realized in the bathtub that if Vermeer had a mechanical way to do that, it would explain the paintings. I thought of this idea of a mirror sort of hanging in space and matching the color at the edge of the mirror. Basically, we know these artists could trace shapes with optics, but this was a way to trace colors. I thought this was a really important idea. First, I went on the internet to see if anybody else had been thinking about it and they weren’t. So I tried an experiment and it worked great.

How did this project evolve into a documentary film with Penn & Teller?

JENISON: About the same time, Penn Jillette wrote me an email. We’ve been friends for 25 years. And he said, “I am desperate for an adult conversation. I’m just talking to my toddlers and Teller and I haven’t been able to hang out with friends. Can you come to Vegas and talk to me?” It sounded desperate. I went out there and I said, “Are you okay” and he said, “Yeah. But can we not talk about show business. I’ve had it up to here.” I said, “Okay. Well, what do you know about Vermeer?” and he said, “Dutch painter. I went to his show in New York. Realistic images.” I said, “Yeah, I think I maybe figured out how he did it.” He said, “What do you mean?” and so I explained it to him. I actually had a video on my camera showing the view down through the lens, the mirror, so he could see how it worked. He said, “I totally get this. What are you going to do with this?” And I said, “Well, I’d like to paint something that looks more like a Vermeer. Set up a room and actually try to paint it and maybe make a YouTube video about it.” And he said, “That’s a stupid idea because this should be a real film.” And that’s how it started. That was in February of 2009. Penn just took the bull by the horns and made it happen.

What was it about this epic research project that made you say, “I’ve got to do this” and convinced you to commit 8 years of your life to it?

JENISON: I love the power of an idea, an invention. An invention can change the world. Ideas are powerful. This particular idea is not a cure for cancer or anything like that, but I felt like it could be a fundamental change in art history if I was right. It’s not that I see it as my job to change art history, but it looked like something that needed to be explored. And then, once Penn decided to make a movie, it got bigger than life, and I did a lot more work than I would normally do. I wanted to make that room look perfect and I wanted the painting to be as good as I could make it. At the same time, I had to be covered by up to nine cinema cameras at any given time which made the whole thing go a lot slower. So, I think left to my own devices, if Penn hadn’t started making a movie, I would have done a simpler experiment and I wouldn’t have taken years out of my life to do it. Once I got going, Penn and Teller said, “This is great. C’mon, we’ve got to do this.” We thought it’d take maybe a year and it took a lot longer than that. But I’m glad I did it. I’m glad I had the time and resources to do it because it was a real thrill.

You seem to share several things in common with Vermeer in the sense that you’re meticulous, innovative, and enjoy puzzle solving and figuring out how things work. Do you think in some ways Vermeer and you are kindred spirits?

JENISON: Maybe. I don’t know. There is so little known about Vermeer, but my mental image of Vermeer is kind of like a fellow geek, a computer nerd that just happened to be born 350 years early or he’d be writing video games or making Toy Story 4. I think that’s the kind of guy he was. I did a lot of research on Dutch life at that time and the way people thought, and it is quite consistent that he wouldn’t have looked at it as cheating. He just would have looked at it like we make movies, that it would be just another tool to get a perfect image. That’s what movie makers do. We don’t say, “Hey, that would be cheating” if we have to use computer animation or something like that. They were renaissance men. They knew art and science at the same time.

What was your reaction when you were granted access to view Vermeer’s The Music Lesson in the Queen’s Collection in the Picture Gallery at Buckingham Palace?

JENISON: Well, it was both good and bad to see the Vermeer at Buckingham Palace. Good in that it kind of confirmed what I was thinking more so than the reproductions. The reproductions are too colorful and really blurry. When I got there, I could see that the colors were far darker, which is kind of what I expected, and there was a lot of detail. Every little decoration on that harpsichord was there and that was the bad part. I knew that it was going to be an incredible amount of work to emulate that, and I wasn’t seeing that sharp of an image in my machine at that time. And so, I just got a sinking feeling. I mean, it was a beautiful thing to see but it really set me back. It threw me for a loop. I actually had to come up with another design to make it work.

What did you find was the most challenging aspect of this project?

JENISON: The worst day was just seeing the painting at Buckingham Palace and knowing that my machine was not going to work. It was just a horrible feeling. It was a beautiful feeling to see the painting finally after staring at these fuzzy reproductions. Other hard parts were grinding the lens. You had to learn a lot to be able to grind those lenses to be authentic to the 17th century. And then, there was just a huge amount of research that I did before getting started, and that was a big, big job.

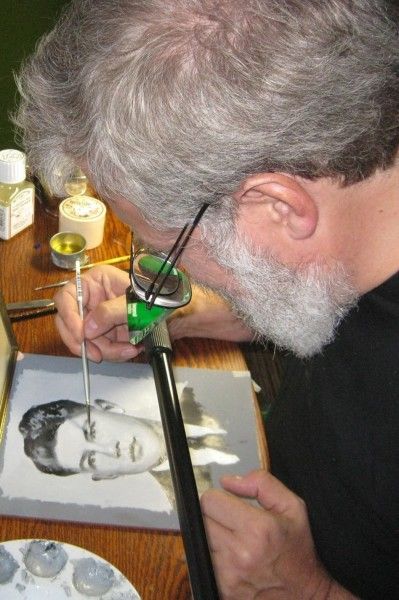

I’m fascinated by how you duplicated the tools and materials that Vermeer would have had available and used in order to recreate The Music Lesson and test your theory.

JENISON: Yes. If I’d painted Girl with a Pearl Earring, it might have been interesting, but I never would have learned things like that distortion in the seahorse pattern. That’s pretty good evidence that he was using a very similar setup because it was a very specific kind of distortion. It wouldn’t happen in a camera obscura. It would only happen if you were using this curved reflector. It was a very good thing in retrospect that I chose The Music Lesson even though it was probably the hardest one I could have chosen.

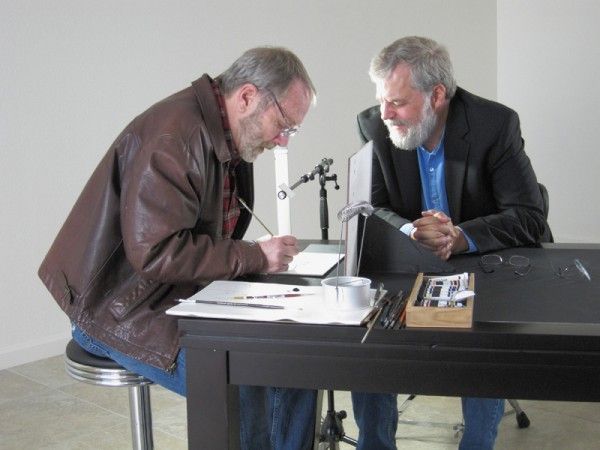

What was it like meeting David Hockney and having the opportunity to share your ideas and show him what you had discovered?

JENISON: Well David Hockney got me started in a big way on this when I read his book (Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering Techniques of the Old Masters). My daughter gave it to me for Christmas one year. There was a lot of hard science there, and I’m fascinated by ancient technology and how these ideas came to be. Penn and Teller had worked with David Hockney years ago, and they said, “We should ask David Hockney if he wants to be part of this project.” It was impossible to get in touch with him. He has created a moat around himself so that he can paint all day. He wants nothing more to do than paint all day. It took a long time. Finally, he invited us over. He didn’t want to be filmed because he’s had some bad experiences with documentary crews, I guess. But he served this huge spread of lunch to us, and we got to talking about optics and art, and he got more and more interested in what I was talking about. We got to the point in the conversation where we said, “Do you want to see this thing?” And he said, “Yeah. Let’s go up into the attic which is where his atelier is in Bridlington on the Yorkshire Coast.

On the way up, Teller walked up to David and he said, “Would it be okay if we taped this. If you don’t like it, we of course won’t do anything with it, but we think it’s going to be very interesting to you and we’d like to see your reaction.” He said, “Yeah, okay.” And so, Farley (producer Farley Ziegler) had two consumer camcorders in her purse. She pulled them out. We had these little pocket voice recorders from Radio Shack, stuck them in our pockets, and the whole thing was a guerilla, no budget production. And you can tell looking at it. He looked through the mirror and he said, “Wow! Yeah, this is something.” That was a great feeling. And then, we went back later after the painting was finished, and you see in the film what his reaction was. Since the film’s been finished and out there, I’ve gotten to know David and he’s been very supportive of the film. He’s just a wonderful person.

Do you think Vermeer’s reputation is diminished in any way because he used optical technology to paint photorealistic images? Or was he an artistic genius way ahead of his time who was innovative and drew on principles of photography centuries before it was invented?

JENISON: It depends on what you mean by genius. A lot of art historians have made him almost a mythical being. If you try to paint a Vermeer, if you’re an art student and say, “I’m going to learn how to paint like Vermeer,” you can’t do it. People have tried. I know a concert pianist, and we were talking one day, and he said, “It makes me mad when people come up and say I’m a genius because that’s not what I do. I work really hard. I practice for 8 hours a day and continue to do that, and I’ve been doing it since I was little. They think I can just do this effortlessly. They don’t know what I put myself through to be able to do that.” I think really genius can backfire on you if you use it in that sense. I don’t think you have to have a high IQ to do this. I don’t look at myself as a genius. Vermeer certainly had a spark that made him decide what to paint and to make those beautiful images. That doesn’t change regardless of how he did it. He did it. Dutch art at the time was going for realism. They thought that was the pinnacle of art to be realistic so that it would be almost like looking through a window to see a painting. We know that was what they were trying to do. I think Vermeer just thought, “I’ll go the extra mile. I’m going to invent something to get an even better and more beautiful image.” That’s my guess.

What did you learn about yourself in the process of making this film?

JENISON: I think probably that I was capable of doing a 10-year project. In my day job, I do some big projects that take one or two or three years, but I have a lot of help. And this was a very unique thing. As you can see there, I did everything myself. I’m really not capable of doing that. I have a long attention span, but not that long. But it was Penn and Teller and their cameras and their conference calls that kept me going. I guess what I learned is that I could do that. (Laughs) I don’t want to do it again, but it’s a great feeling. I’m so glad I did it.

What was the most fun aspect of solving this art history mystery?

JENISON: The last days of painting the rug were the funnest part because the stress started to melt away. When we started, we didn’t know if it was possible and there was always that risk that it wasn’t. In fact, it was a very real risk because my first idea didn’t work. I remember going and unlocking the door one morning and saying, “I get to paint today.” Prior to that, it was like, “Okay, another day of drudgery.” That was the fun part, just finishing it. And then, it was really cool to see Penn and Teller at work. It was totally unexpected what they came up with to me and probably to them. It’s a very strange film and apparently people really respond to it. That’s been fun to see.

What do you think makes this confluence of art and science so fascinating?

JENISON: That’s a good question. I’m fascinated because these works of art are a window into the past. We know a lot about the world after photography was invented. We know, for example, exactly what Abraham Lincoln looked like. We know what people sound like after the late 1800’s because the phonograph was invented. Images give you a sense of the time, whether they’re painted or captured. The Vermeer thing was especially fascinating to me because I felt that now we were seeing color photographs far older than we had before. That’s what kind of turned me on about it. And if I’m right, they really are. Vermeer’s room did look exactly like that, and those people looked exactly like what you see there. Again, not a cure for cancer, but it’s fascinating to be able to look back in time.

It’s intriguing to discover that an artist who was painting centuries ago might have been using today’s technology back then.

JENISON: Yes. Another cool example is this brass clockwork computer they found in a Greek shipwreck that dates back to B.C. Nobody knew. Nobody had any idea that they had navigation computers. A lot of technology has been lost that way. For example, they forgot how to make concrete for about a thousand years after the Romans. The English rediscovered it. It’s cool stuff.

What was your reaction when you first heard that the film had been short listed for the Oscars?

JENISON: They selected the nominees and we didn’t make the final nomination, but being shortlisted was just a surprise out of left field. That’s the last thing we expected. Like Penn said, it’s an honor to be nominated to be nominated on the short list. Yes, that was wonderful. Teller has never directed a feature film before and he was just giddy and said, “I can’t believe this is happening!”

Isn’t it great how coming to Las Vegas for that conversation with Penn worked out?

JENISON: (Laughs) Yeah. Or maybe not. Maybe I could have saved a lot of time.

What are you working on next?

JENISON: I’m back to my day job, and I don’t have another obsession lined up, but I’m still working on this one. I started writing a book about it a long time ago. I’ve never written a book and I don’t feel qualified, but I learned so much that needs to be put out there. People are real interested in some of the details of how this worked, and I learned a lot of other interesting things about Vermeer and other painters. In particular, I’m looking at Caravaggio who painted long before Vermeer and who set the art world on its ear with his painting style, the chiaroscuro, and started a whole school of art, the Caravaggisti (the Caravagesques). It looks to me like he may have been using a very, very simple optical set up that would lead directly to a painting like that. They’re very unusual. I’m not going to make a film, but maybe I’ll get out my paints again and try that.