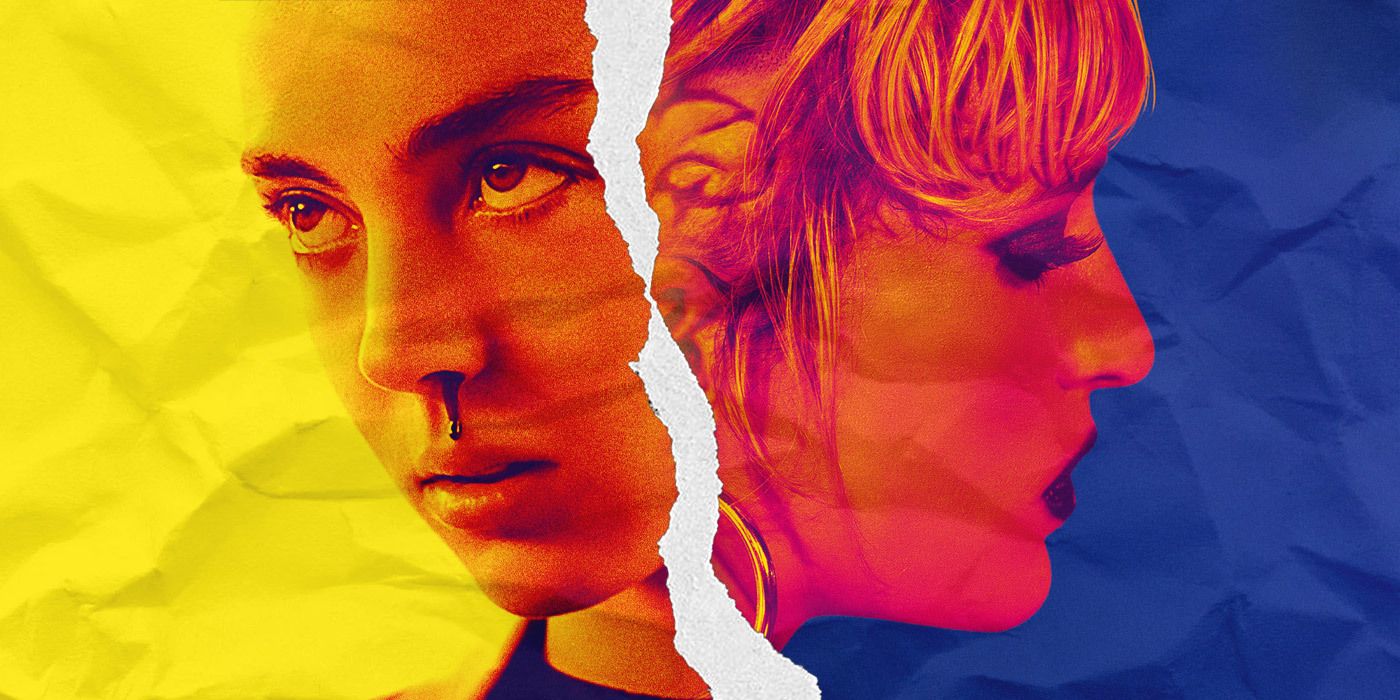

The relentless physicality of Julia Ducournau’s films can be horrifying. Her debut, Raw, became notorious for causing a few viewers to pass out during its screening at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2016. Indeed, the French filmmaker shares predilections for blood and guts with the likes of David Cronenberg — but even as she renders her subjects using genre tools, she brings a unique, lyrical sensibility to her work. Her shock and gore are not as simple as pleasure and pain. Ducournau’s use of violence and viscera in Raw and her subsequent Cannes Palme D’Or winner Titane (2021), elevate her characters' emotions and transform their stories into startlingly potent statements about universal human experiences: love, desire, intimacy, belonging. Both of Ducournau's films function as extended metaphors, turning the ephemeral into the physical and making the difficulties of love and lust legible on the body.

At its core, Raw is a coming-of-age story, not a horror film—but Ducournau leverages body horror tropes to convey just how terrifying and bewildering girlhood can be. In Raw, Ducournau portrays a girl’s awakening to herself through the metaphorical vehicle of cannibalism. Justine (Garance Marillier) arrives at a grim-looking veterinarian college as an awkward, doe-eyed freshman. The school immediately proves to be both socially and academically extreme. At night, the upperclassmen haze the freshman in intense stunts that evolve from the typical — sweaty, drunken bacchanals — to the more tortuous. In the first scene of classes, instructors are prepping a horse for a surgery. They administer tranquilizers, then slide a plastic tube down its throat. And this is the first taste we get of the clever ways in which Ducournau conveys “normal” feelings through unusual imagery; it’s clear from Justine’s panicked reaction to the horse’s procedure that Justine can relate to the constrained animal.

As the movie progresses, Ducournau further dissolves the distinction between human and animal, good girl and naughty woman. After a harsh day of hazing involving a lot of animal blood and raw rabbit kidneys, Justine wakes up in the middle of the night with a full-body rash, violently red and itchy. She begins scratching furiously, and the phrase ‘scratch an itch’ comes to mind — Ducournau has clearly embodied it here, taking the notion of an inkling or an urge and painting across Justine’s skin, forcing her to react to it. As her feelings awaken, so does her flesh.

“I am hungry. It feels like my stomach is always empty,” Justine tells the doctor who treats her rash. This notion drives the rest of the film, as both Justine and her older sister Alexia (Ella Rumpf), also a student at the school, become completely governed by their raging hunger. In the cafeteria, Justine, still supposedly a vegetarian, looks longingly at burger patties. Unable to resist, she slips one into the pocket of her white lab coat, where it creates a conspicuous stain. To make matters worse, the cashier forces Justine to take the patty out of her pocket so she can ring it up; Justine holds it dripping in her hand, abject. Watching this scene unfold feels like watching classmates making fun of a girl getting her period during P.E. or a presentation. It's both completely mundane and quite uncomfortable to behold—adolescence in a nutshell.

Ducournau explores the social ramifications of self-exploration through the guise of Justine's growing hunger. As Justine feeds her desires, they only seem to grow. Justine and her roommate Adrien (Rabah Nait Oufella) go get shawarma at a gas station, where a sex worker starts talking to them. He rubs Adrien’s face, explaining that he has a pig in his truck for blood transfusions. “Pigs are almost like humans. Have you learned that yet?” he asks. As he’s talking, Justine starts shoving as much meat into her mouth as she can manage —and later that night, Adrien catches Justine eating raw chicken from the fridge. She seems almost helpess, as confused by her hunger as she is desperate to satiate it. But if Justine is merely a pig now, repulsive and self-indulgent, she is about to become a much more fearsome animal, baited by her sister.

Alexia teaches Justine how to kill discreetly to satisfy her needs, but the sisters begin to set in on each other. Toward the end of the film, the sisters start fighting publicly, attacking and biting one another, sucking at the wounds they're inflicting. The other students stand by and watch them, horrified. This evokes the shame and secondhand embarrassment of any public display of misconduct, but Ducournau turns standard schadenfreude into pure disgust as the sisters draw blood. As with the rest, Ducournau uses the grappling sisters as a metaphor to emphasize the difficulties of becoming a “woman,” of being required to manage a messy body and all its deepest desires without stepping on (or eating) any toes. Raw's fleshy metaphors suggest these expectations are impossible to meet, conjuring feelings of fear and frustration that anyone could relate to.

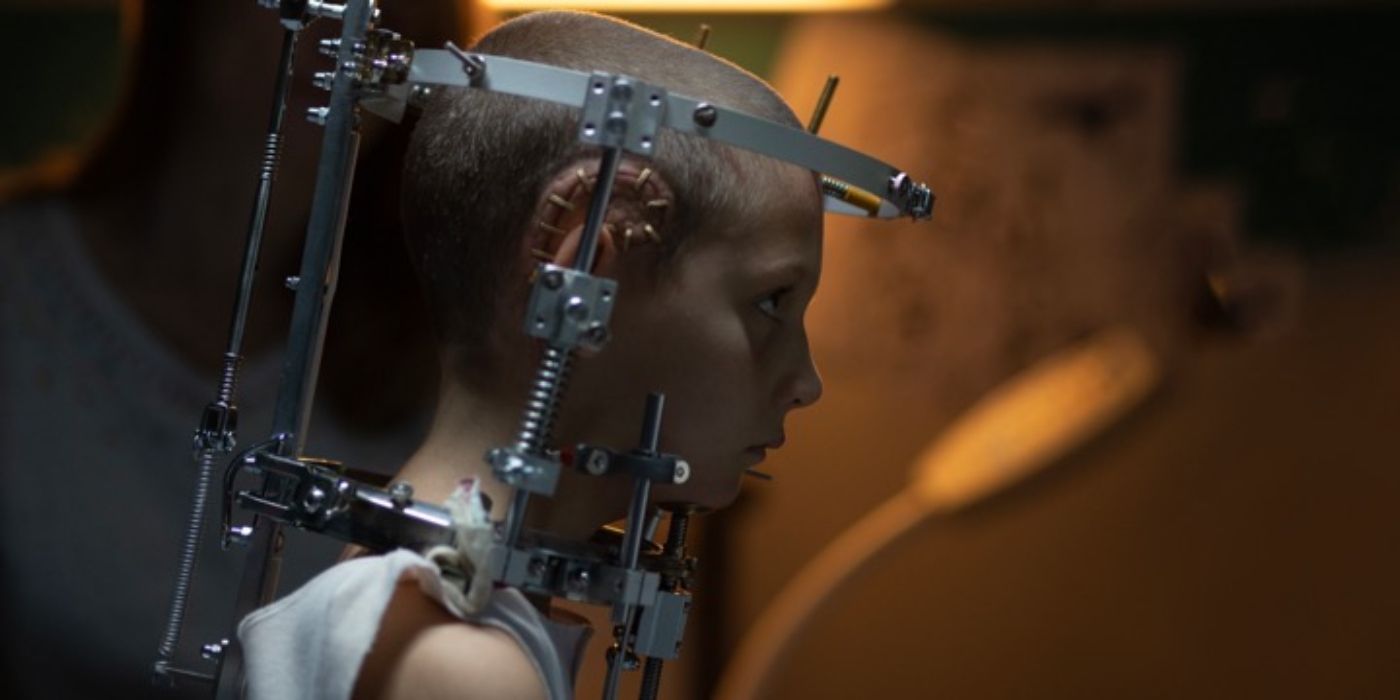

Titane is a bit more diffuse and unpredictable. In her second feature film, Ducournau interrogates the (often gendered) experience of vulnerability through a metaphorical cycle of traumatic injury and shocking violence. Ducournau transforms the phrase “like a machine” into a visceral metaphor, and a line of inquiry: how might a girl become a machine? What might that look like? Ducournau explores this second question, in particular, with relentless curiosity and vibrant imagination.

As a child, Alexia (Agathe Rouselle) was literally wounded. In the beginning of the film, we see her father scold her while driving, causing a car crash and a devastating skull injury. In the aftermath, Alexia emerges from the hospital with a steel plate in her head, a strange love for the family’s car, and a dangerous disdain for parents. Alexia’s head wound — the titular titanium — is a metaphor for her trauma, physical and emotional, and, though we receive no explanations as to why, the injury seems to inform her subsequent actions in shocking ways.

Whereas Raw puts the relationship between humans and animals under a gory microscope, Titane considers other dichotomies: the ones between human and machine, feeling and unfeeling. For all intents and purposes, adult Alexia, now an erotic dancer who performs in car showrooms, is a machine. This is the film's most perplexing and shock-inducing metaphor. Alexia is cold and murderous, ruthlessly slaughtering both men and women; she has sex with a car after work, and the encounter results in an oily, gut-wrenching pregnancy. The premise is absurd even in the context of the film, but Ducournau is more interested in evoking emotions and unraveling stereotypes than she is in any kind of sense-making.

As it is in Raw, the “flesh” in Titane becomes a metaphor for humanity and all the feelings that come with it, feelings which Alexia so desperately seeks, yet fervently sabotages. Ducournau continues to show flesh as a complicated problem for Alexia, whose desire for it — and desire to be rid of it — are at odds. The results are extreme: there is sex, and then there are dead bodies; she’s wanted for numerous murders, including those of her parents. Her own culpable body is a problem. To hide, Alexia decides to pose as a missing boy, Adrien. She mauls her own face, cuts her hair, binds her breasts, and tapes down her pregnant stomach to convince Adrien's firefighter father, Vincent (Vincent Lindon), that she is his son. Try as she might to erase her body, Alexia's skin offers stubborn evidence: a prominent scar on her head, mottled bruises from binding.

Vincent has his own fleshy traumas and violent coping mechanisms. He lost his son (literally, a missing body), and his aging body is deteriorating — he regularly shoots steroids to combat this reality. But unlike Alexia’s, Vincent’s Achilles’ heel is immediately obvious. He becomes emotionally attached to and inexplicably protective of Alexia as Adrien, ignoring all logic, even after discovering ‘Adrien’ is not who he says he is.

Though Alexia uses Vincent’s vulnerabilities to her advantage, she eventually finds herself rather attached to him, too. If she is a machine, she is one on the verge of breakdown, her insidious desire for connection resulting in severe malfunctions. This is another one of Ducournau’s metaphors: the body as a failing machine. In the end, Alexia’s body does fail her — and it’s the titanium plate, the very thing ostensibly holding her together, that kills her. But not before she feels something true and good. Something like love.

Perhaps it should be no surprise that with all their gore, Raw and Titane wear their hearts on their sleeves. These are ultimately films about feelings, feelings that rise from somewhere deep in the body — and their gruesome metaphors create physical discomfort that urges viewers to consider the true nature of their own.