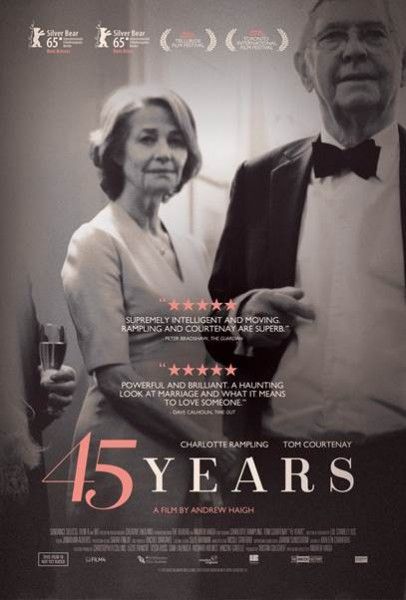

In a superbly calibrated performance, Tom Courtenay looks back on the road not taken in Andrew Haigh’s thought-provoking third feature, 45 Years, adapted from David Constantine’s short story, In Another Country. Haigh captures with unforgettable acuity the vulnerability of a seemingly strong marriage that begins to unravel when an unexpected letter arrives from Switzerland informing Geoff (Courtenay) that the body of his former lover has been found in a glacial crevasse. The surprising discovery calls into question his longtime marriage to Kate (Charlotte Rampling) and the life they’ve built together just days before their 45th wedding anniversary celebration.

In an exclusive interview with Collider, Courtenay revealed his reaction when he first read the script, why he found his character so relatable, Haigh’s naturalistic directing style, what it was like working with Rampling for the first time, their sex scene together, his fun improvisations that ended up in the film, his moving speech in the final scene, being an icon of British cinema, working with Tony Richardson, how he was drawn to theater because he didn’t like making films at first, his reaction to the film’s Oscar buzz, and his upcoming role in Dad’s Army with Catherine Zeta-Jones, Toby Jones and Bill Nighy.

Check it all out in the interview below:

What was it about this story and your character that made you say I’ve got to do this?

TOM COURTENAY: Well, it’s that thing of a man in his 70’s looking back at when he was young and wondering about it and how his life might have been different. That was the key to it really. And, of course, all of a sudden he’s in a love triangle between a girl who’s been dead for 50 years and the woman with whom he’s about to celebrate 45 years of marriage. It has to be a good part.

This is such a thoughtful, nuanced story. What was your reaction when you first read the script?

COURTENAY: I read it on my iPhone when I was away from home. I read it right through. I remember my first scene when he gets the letter. I found it very powerful. It just took me over. It’s so thrilling and it’s never happened before. It was completely out of the blue, out of nowhere. There were other things. I was in the play Billy Liar. I was in the play Quartet. It was my idea because I’d seen the play, Ronnie Harwood’s screenplay. With The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, I’d met Tony Richardson 18 months before. But this, there it was. It would start in six weeks or so in Norfolk. It had Charlotte Rampling. It’d never happened like that ever, something like, “Here you are. Take that.”

I was just overwhelmed by that first scene and also this extraordinary idea that I always look down, at the girl down in the ice, frozen. Like his youth, it’s frozen down there, because it’s quite a cliché of an old man thinking of his lost youth. But there it is. It’s no cliché. It’s just a wonderful image, and that’s the powerful image from the story. There’s not that much else in the story. The film is mostly Andrew’s invention of the marriage, of the anniversary. And so, the timing of the letter just a few weeks before they’re having their anniversary is Andrew’s invention. The description when he talks about how the girl died, and he heard the laughter before her scream, and all that, that’s all invented by Andrew.

For someone who’s much younger, Andrew’s perspective on relationships, old age, jealousy and forgiveness seems very perceptive in terms of how he’s written these characters. Would you agree?

COURTENAY: Yes. It’s strange to meet him and think about that, because it’s so heartfelt from my point of view how the character feels. I identify absolutely, totally, and yet it’s written by a much younger man. But he says people can look back at their lives at whatever age they are. When you’re maybe 15, you can look back at when you were five or something. (Laughs) I don’t know.

I understand Andrew likes to do long takes to let the action play out and draw the audience in, and not so many close-ups. What was that process like for you?

COURTENAY: He said before we started that he likes very naturalistic two-shots and not a lot of close-ups. He said that’s how he would do it, so I was prepared. I learned it very thoroughly. He has a naturalistic style which suits the film very well. Sometimes I’m out of shot. I’m often not seen, but heard. I’m cool about that. It doesn’t matter. Sometimes we’re almost both out of shot. Sometimes he’s on the back of both of us and we’ve got our backs to the camera. It makes it seem lifelike and natural. It’s very uncinematographic, and yet he has a wonderful visual sense it seems. It looks very beautiful. It’s like them having their lives in their house.

When you’re in a two-shot together, you can’t be the same as when you’re both in singles. Try as you will, it cannot be the same as when you’re in the shot together. It simply cannot be. It’s physically impossible. You’re behind the camera desperately wanting to help your colleague. When it’s just you, on your own, it can be self-conscious in a way that you’re not when we’re just talking, you and I, and then all of a sudden it’s me and then it’s you. The two-shots were probably more natural.

It gives you a sense of who this couple is, how they live, and what their life is like.

COURTENAY: Yes. He knew the area very well, and he found this cottage, and we had a little cottage next to it where we’d go and rest. The whole thing was very well organized. We shot in order, which helps. I’m almost 100 percent sure, although not quite 100 percent. I think we had to go to the factory on a certain day, that extraordinary place. It was this huge, great ugly thing, and then you pan over and there are the beautiful reeds of the Norfolk Broads. But generally speaking, we started at the beginning and finished at the end, which really helped, but we didn’t do all the bedroom scenes at once. We went from one scene to the next in chronological order, which does make it easier.

How challenging was it for you to shoot the sex scene with Charlotte Rampling?

COURTENAY: To me, not at all. It’s so ungratuitous. It so comes out of their situation and trying to capture his youth with her, not with the girl in the ice. It was an attempt to bring that back. So, I found it not embarrassing or difficult at all. I was quite happy to remove my underpants. We knew one another by then. We laughed and made it light and jokey. That’s the way to do it.

Both of you are icons of British cinema. What was it like working together for the first time?

COURTENAY: We’re both so well cast. It just seemed to work. When people say it looks as though we’ve worked together forever, it’s not so. We never had before. We didn’t rehearse much. We did have a day where we read through our scenes with Andrew. Then Charlotte and I went off and had a drink and a bit to eat. That was our preparation. We worked obviously on our own. My part often speaks at length and I loved that. I could get into it by learning those long speeches. There were about three or four. I find the best preparation always is to learn the lines. Also, I’m pathological about it. I feel once they’re in me, it helps me to create the part.

Did Andrew give you room to improvise or did you stick pretty close to the script?

COURTENAY: Oh yes, Andrew had no objection to putting extra words in. Some directors will say, “Oh, I’ll have to ask the writer if that’s okay.” But, he was the writer. One of my favorite ones was a tiny little thing when he says, “We used to get up at 4:00 in the morning,” and I just said, “Four in the fucking morning.” It was the extra “f”, just a tiny little thing like that. One of my biggest improvisations, which I was sure wouldn’t be in the film, was about the birds when they’re walking. He tells her how the Treecreepers fly down and work their way up the tree, which they do. It’s all orthnologically correct. And the Nuthatches fly up and work their way down the tree. But I just did it for fun, not thinking it would be in the film, but it is. I also like to put in the odd little joke, like when he says, “I managed to mend the lavatory without cutting my finger off.” It’s little things like that. I never said anything. I just slipped them in. And then, there’s the one when he says he’ll make her some scrambled eggs when he’s being a good boy at the end. As I left the shot, I said, “Have we got any eggs,” and he kept that in. So, it was a bit of fun. It’s nice.

Geoff Mercer looks back on his life and ponders the road not taken, as in the Robert Frost poem. Was he relatable to you as a character and have you ever had that experience in your own life?

COURTENAY: Oh yes, The Road Not Taken. You’re spot on. I think of that poem all the time. When I talk about the film, I mention it, The Road Not Taken. The last time, I just saw the beginning of the film while Andrew was checking the print. We were not going to watch it. He was just checking the print, and I’m sure, right at the beginning, there are the start of two paths. It’s one of the first images of the road not taken. It seems to me so natural, certainly to me, and I can’t think I’m alone, that people look back on their lives and see how they could have been different. It’s human. I did the solo that my friend, Albert Finney, came to see twice. It’s this Russian play that’s called Moscow Stations (the stage adaptation of Venedikt Yerofeyev’s autobiographical novel). He’s a drunk, and he wakes up in the morning, and he says, “Shall I go left or shall I go right?” I remember Albert quoting it, “Shall I go left or shall I go right?” It’s The Road Not Taken. That’s what our lives are. Sometimes when we go for a walk, we don’t know which way we’ll go. People say “It’s just looking back,” but it’s the only direction we can see in. You can’t see forward, in front of us, except physically to the end of that room. But we don’t know what’s going to happen tonight. It seems to me utterly natural to ponder about your life. Not all the time. Also, I think one of the things that interests people is that it makes them start thinking about their own relationships, and do we have secrets from our closest. Well, of course, we do. It’s just natural. It doesn’t mean to say I don’t love my wife, but I don’t come in and say, “Oh Isabel, I just saw this 19-year-old girl who’s stunningly beautiful.” Of course, when you get to my age, that’s what you do, but it doesn’t mean to say you don’t love your wife.

Were there any surprises you encountered in the process of making this film?

COURTENAY: Let’s see. Oh, I know. It’s the only comment Andrew made on his script, which was that Geoff’s speech was moving. “It’s terribly moving,” he said. And I couldn’t see it at all. How is it moving? But when I got up to do it, it was moving. I was very moved. I wouldn’t have acted being moved if I hadn’t been. I just was. So, that’s something Andrew knew better than I did. There was a moment when I’d done that speech and I sat down. I knew I might have to do it again, but he said, “We’ve done it on you now.” It was all on me, because Charlotte was sitting there. He didn’t use any of the cutaways as we called them. He didn’t use any. I got a sense of well-being. It was as though my blood had flown in a way that was good for me. I suppose it made me think, “Well I need to be doing this acting for a bit longer still. I don’t want to stop just yet.”

You took a break from films for over a decade to do theater. How has your experience in the theater informed the way you approach film and which medium do you prefer to work in more?

COURTENAY: I probably had to get used to the process again. I think Charlotte is more used to it, because she hasn’t done much theater. She was more used to it than I was to start with. Also, I get quite impatient filming because I learn it desperately well, and I don’t like to do too many takes, and sometimes you have to. When I was younger, I couldn’t manage that. In The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, I think Tony Richardson knew I wouldn’t do that many takes and he never asked me to. But, the whole filming process I’m better at now than when I was younger. I didn’t like it at first. I wanted to go into theater. Now it’s the other way round.

I enjoyed how this film examines a stage of life that’s not usually seen in films today. Are you excited about the Oscar buzz your performance is generating?

COURTENAY: I don’t think there’s anything I can do about that. Nothing. People do like it, and people like it in all different ways, and people say different things about it. So that’s nice. It’s got to be nice. And this promotional stuff, you have to give of yourself. You have to. Otherwise, what’s the point. And you’ve got to risk sounding stupid. You’ve got to try. But I must say, more than anything else I’ve been in, the journalists have been easier to talk to because they find it very interesting. Maybe it’s something slightly different from what they generally see. I don’t know. But they’re engaged by it, and therefore, it’s easy to talk to people about it.

What are you working on next?

COURTENAY: I don’t know. The last thing I did aired its last episode this evening in England. It’s a series called Unforgotten. It’s a whodunit. A body is discovered, and it was traced to having been murdered it looks like in the 70’s, and there are four lines of inquiry from these elderly people, one of which is me. And this evening, on ITV, I tell the story of what happened. That was a good spiel. That was 12 minutes’ worth talking. The director told me he measured it. And that was my last thing. I’ve got a bit in Dad’s Army.

I watched the trailer for that this morning. It looks like a lot of fun.

COURTENAY: Yes, it will be, I think.

It’s got a great cast, too.

COURTENAY: Oh yes, very. Catherine Zeta-Jones is very sweet. She left a poster on the dresser for me to sign. And Toby’s terribly good in it. Toby Jones. And Bill Nighy. But as for what comes next, I have no notion, and I’m really very happy with that. I don’t have to work all the time.

You live in Putney, England. How has your visit been to Los Angeles so far?

COURTENAY: This is my second day here. I arrived Tuesday evening at the Chateau Marmont. I was at the Chateau Marmont 50 years ago for three months doing a film called King Rat. So, it’s different and also it’s such a long journey. I took two little sleeping pills last night, one and then the next. I was off a bit, but I’m okay. I mean, it’s not difficult to talk about the film, because obviously it means a lot to me, to Charlotte, and to Andrew. I hope if I have some time in the morning, I can walk out of the Chateau Marmont and walk along Sunset Boulevard, and nobody will arrest me. It’s the walking that I miss in Los Angeles. I love to walk as I do in London. I spend a lot of time being in plays in New York, and there you walk everywhere. So, I hope I can have a walk in the morning. The temperature has been so variable. I brought my pullover.

When you look back on your career, are there any roles you’ve always wanted to play that you haven’t yet?

COURTENAY: Actually not. Occasionally, I see a part I would have liked to play. In Billy Elliot, I would like to play the father of the boy who was a dancer, because I imagine if I had wanted to be a dancer how my father would have been, not liking it, and then being full of it. Occasionally, I see something that I think is very me. But generally, I’m happy to see what comes along, if anything. (Laughs)

45 Years opens in theaters December 23rd.