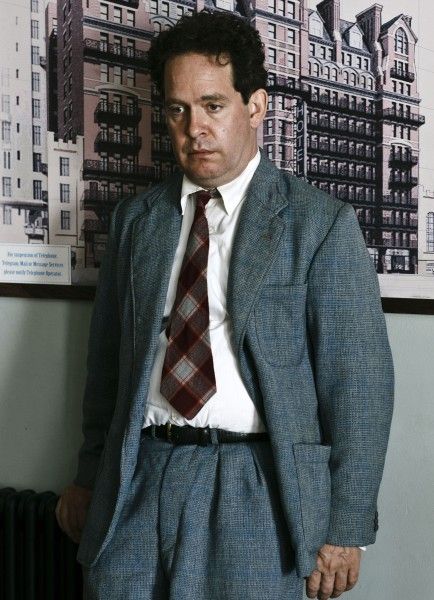

Written by Andrew Davies and directed by Aisling Walsh, A Poet in New York explores the final days of adored poet Dylan Thomas (played brilliantly by Tom Hollander). As the creator of some of the most memorable lines in the English language, he became a much-loved celebrity in the US. But his failing marriage and wild lifestyle led to his untimely death in 1953, at the age of 39.

During this exclusive phone interview with Collider, actor Tom Hollander talked about why he ultimately signed on to play Dylan Thomas, the grueling shooting schedule, the experience of playing someone so self-destructive, why he’s so proud of his performance, and that he hopes viewers can find this story relatable. He also talked about what he looks for in a project and role, and his wild experience with motion capture and voice work on Jungle Book: Origins, directed by Andy Serkis. Check out what he had to say after the jump.

How did this come about, and what sold you on it, as far as feeling comfortable and confident that you could take this on and do Dylan Thomas justice?

TOM HOLLANDER: Well, you’re right, initially, I didn’t think it was a particularly good idea. I’m not Welsh and I didn’t know that much about him, and I saw that he’s a huge icon of Welsh-ness. Also, the schedule was terrible. They wanted to do it in three weeks, but on the other side of it, it was such an opportunity. Also, this was a script by Andrew Davies, who is one of the great television screenwriters of our day, on this side of the pond. So, I thought, “You’re just going to have to man up and have a go.” But, the caveat I had for myself was to just try to get the voice. So, I met with the director and said, “If I can do the voice, then I will be on board.” Then, I went and met a great voice coach, Jill McCullough, and worked with her to try it out. She was great. She gave me the confidence that it would sound okay. It sounded within my reach. Once I’d established that, I thought, “Okay, get on with it!” So then, I did. And then, I did lots and lots of listening. I listened to his recordings and tried to get into it that way.

This is a very beautifully crafted screenplay by Andrew Davies. If you were going to take on someone like Dylan Thomas, was it essential that the screenplay was there, and that you didn’t have to try to make it better?

HOLLANDER: Well, yeah, that’s for sure. The screenplay was amazing. (Director) Aisling Walsh has done some beautiful films, and she got a BAFTA, the year before. And I knew the executive producer, Griff Rhys Jones, who’s an extremely clever, brilliant man. The downside was simply the schedule. They didn’t have enough money, so they were doing a 75-minute film in three weeks, which is quite a lot. And I was in every scene, so it was going to be punishing. That was the thing to overcome. But, Aisling Walsh was so well-prepared. It was going to affect her, as much as it was going to affect anyone. It affects her more than anyone, really. She said, “We’ll get through it. I’ve done this before. The way to do it is to be really well prepared and know what you’re going to do. I need to know how I’m going to shoot it, but we’ll get there on the day. We’ll know what the scenes are, and we’ll go for it.” It wasn’t one of those shoots where you can spend all day working out how a scene works, and shoot it from various different angles, speculating what might be the best one. She had to make pretty strong decisions up front, and she did. And I had done my homework, as much as I could, so I was well-prepared, by the time we got to do it.

That schedule would have been grueling, even if you were making a comedy, but this film is very intensely emotional.

HOLLANDER: I actually don’t subscribe to the notion that comedy is easier than drama. When you’re trying to be funny and you’re not funny, that’s really terrible. It’s a horrible feeling. For some reason, all of the really punishing emotional stuff and the most grueling scenes tended to be in Chelsea Hotel, and they were all in the first week of the schedule. The last week of the schedule was all of the stuff on location, which were happier times, in terms of the story. I was eating myself stupid until the first week, and then I stopped eating because it was making me feel ill. From pretty much the beginning of the first week, I was on a normal-ish diet. By the time I got to the third week, the weight was starting to fall off of me, which strangely coincided with going back in time a few years. The stuff in Wales was supposed to be about two years before his final trip to New York, so it worked out quite well.

What are the biggest challenges in playing someone who is so self-destructive? Does that become exhausting, or is it exciting, as an actor, to use so much of yourself?

HOLLANDER: I’m not as self-destructive as Dylan Thomas, but I’ve certainly been around that behavior enough to have found it a release. The thing that I really enjoyed was being able to play misery. I’ve had my moments of feeling miserable in my life, as has everyone, but it’s not often that you actually get the opportunity to indulge that feeling. Mostly when people are depressed or miserable, they have to snap out of it because it doesn’t work. It doesn’t suit day-to-day life. It doesn’t suit work, it doesn’t suit relationships, and it doesn’t suit a functioning existence, on any level, being miserable. That’s why people are always keen to not be miserable. But if you’re actually being paid to be miserable, and to be as miserable as you can be, that’s a very fortunate thing, if you’re prone to occasional lapses of spirit. Not to suggest, in any way, that I’m unhappy as Dylan Thomas was, because I’m not, but I’ve had my brushes with sadness.

Looking back on this, do you feel that you achieved everything that you were hoping to with your performance? Are you satisfied with the work that you did, or is it hard to distance yourself from a performance that you’ve done?

HOLLANDER: That’s an interesting question. It’s always relative. I don’t think anyone could ever be wholly satisfied with their performance. You always think, “Oh, I’m sure I could have done that better.” But generally speaking, I am very proud of this. This is one of my best performances. I hope to be better than this, one day, but it was good for me. I can’t measure it objectively because there’s really no such thing, particularly when you’re looking at yourself. All I can do is measure the amount of discomfort that it causes me, and this caused me relatively little discomfort. I have to say that part of that is based on other people’s reactions to it. Other people’s reactions to it are consistently very positive. I am like a child, in that respect. I hear them enjoying it, and I go, “Oh, good, it obviously worked.” Part of me is blind to it. You’re always a bit blind. If you look at stuff a few years later, you get a more objective look at it. But the first few times you see it, while you’re still close to it, it’s pretty nauseating, watching yourself. You literally think, “Why did I become an actor? What am I doing? Why did I think that was a good idea? I must remember not to watch myself.” But relatively speaking, this is enjoyable. Also, it was a really great part. If you have a great part, you have the opportunity to give a good performance. The greatest actors get the best parts, and the best parts make the greatest actors. There are plenty of people who are as talented, who just never got the part. So, if somebody gives you a great part, you need to do it. That’s why, when they offered it to me, even though I wasn’t Welch and the schedule was horrible, I thought, “I’ve gotta do it!”

When you play a character like this, who was a real man and whose work is still loved, and you get to know him this deeply, do you almost feel a sense of sadness for what he went through and how things ended up for him?

HOLLANDER: Yes, certainly. I feel it’s a tale of a very, very sad man. That was my take on it. That was what I brought to it. That was my only contribution. My intent was to provide him with heart, or to sell that level of self-destruction to a viewer in a relatable way. That’s the challenge, I suppose. I think, if you had actually met him, you might have found him really obnoxious. I might have found him really obnoxious. But if you have to be inside of him, you try to make him relatable to anyone watching, without being overly sentimental or inaccurate. But Andrew Davis, frankly, had already done most of the work. He’d written such a good screenplay, which informs you. It doesn’t shy away from the more excessive aspects of his behavior, but it also manipulates you into feeling moved by watching somebody destroy themselves. And he does that partly by intermingling his poetry with his life. He uses the poetry as a soundtrack to the events. You see him talking to his dying father, and that’s inter-cut with him reciting “Do Not Go Gently Into That Good Night,” and you can see the direct relationship between the life event and the poem. In the film of Amadeus, there are great moments where you’re watching his life fading out and you’re hearing Mozart’s requiem, at the same time. It’s the perfect soundtrack to Mozart’s own life. And we did that with the poetry in this.

You play really varied characters, and you work in both film and television. At this point in your career, what do you look for in a project and role?

HOLLANDER: Well, I like to think of myself as versatile, and I certainly have the most varied career, so I’m very, very lucky in that. I think it sometimes means that I’m not that well-known, and you need to get well-known, at some stage, to get the best parts. [A Poet in New York] is a recent highlight, in terms of casting. At the moment, I’m looking for a contrast to the Dylan Thomas line of characters, not because of Dylan Thomas, particularly, but because Dylan Thomas, in a way, is the most extreme version of a series of slightly defeated people that I’ve been playing for the last few years, which started with the character I played in a film called In The Loop, which was the film version of The Thick of It. And then, that translated into playing this character Rev. I do a TV show about a priest in London, and he is also slightly beleaguered and is subject to fate and misfortune and daily difficulty. So, I am looking forward to finding some parts who are front-foot people who grab life and who are fighters, a bit more, and who haven’t had so much stuffing knocked out of them. The answer to your question is different, depending on what I’ve just done and what I want to do next. At the moment, I’m trying to find those sorts of parts.

How was the experience of voicing a character for Jungle Book: Origins?

HOLLANDER: When you do voices, you never actually do it for very long. All the real work is done with the animators. They take months to do that. You don’t form a relationship with a character for that long. But that being said, I did absolutely love playing Tabaqui, the hyena, who is morally conflicted and a villain, but also quite sweet. He’s hoping to be more of a villain than he actually is. He’s Shere Khan’s (Benedict Cumberbatch) lowly sidekick, which was very funny. I loved it. It was the first time I had worked with Andy Serkis since we did a play together, 20 years ago, at the Royal Court. We did a play called Mojo, and we’ve been friends ever since, but we haven’t worked together. So, that was very, very sweet.

It has an amazing cast, and it was my first venture into the world of motion capture, which is Andy’s thing. That was very exciting. It was a total contrast to anything that I’ve done, partly because you can’t be seen. It’s very liberating. The sky is the limit, really. There’s nothing you can’t do, if you’re in anything animated, because if what you do is terrible, they just don’t animate it. Anything you do that’s useful and that they find inspirational, they can animate it. You can play around like a child mucking around. If you’d have seen it, it’s a bunch of grown men and women, some of whom are quite famous, like Cate Blanchett, basically just pretending to be animals, like children do. There’s no great mystery to it. It’s hilarious, but everyone takes it quite seriously.

A Poet in New York premieres on BBC America on October 29th.