In 1941, director Orson Welles released his debut picture, Citizen Kane, to little financial success but overwhelming critical praise. The film, influenced by the emerging noir style, utilized many of the genre’s mechanics but went far beyond usual conventions, showcasing a varying array of cinematic techniques that would come to be associated with Welles as a film auteur. Welles’s use of the camera, in particular, would come to define him as a unique artist; a broad palette of long takes, abrupt cuts, deep focus shots, and dizzying off-center shots from almost any imaginable angle make up the heart of Welles’s bag of cinematic tricks.

Flash forward seventeen years. In 1958, Universal Studios released Touch of Evil, Welles’s 9th feature film. Like Kane previously, the movie received little fanfare and grossed few dollars, largely as a result of the re-editing techniques that the studio employed to trim the idiosyncratic edges from Welles’s intended artistic design. Contemporaneous reviewers viewed Touch of Evil as little more than a lurid B-picture, a matter not helped by the film’s obnoxious and unsubtle promotion which only highlighted the film’s ‘cheap thrills’ of violence and (relative to its day) sexuality. Despite the scorn critics appended to the picture at the time of its 1958 release, the film today is viewed in a much brighter light by contemporary audiences and film scholars, largely on the back of the inventive camera techniques that form the movie’s chilling backbone. In Touch of Evil, Welles and cinematographer Russell Metty create a dense visual language with their use of camera movement and positioning, all of which add up to an intended portrayal of a world more scary and disturbed than Charles Foster Kane's Xanadu.

Take for example that awe-inspiring shot that opens the picture. It may not be as cited as Welles’s previous bravura long takes in Kane, such as the “Union Forever” flashback sequence, but Evil begins with perhaps the director’s most technically impressive long shot. Lasting 3 minutes and 20 seconds in length, the eternally panning scene (accomplished via crane) establishes the main protagonists, newlyweds Mike Vargas (Charlton Heston), a high-profile drug enforcement official in the Mexican government, and his American wife Susie (Janet Leigh), as they cross the U.S.-Mexico border to embark upon their honeymoon. Via the sheer fluid motion offered by the continuous shot, a clear distinction is made between the two countries and their differing cultures--at this time, serving purely as a visual motif, but a matter which will blossom into one of the film’s themes later on with the introduction of Welles’s character, the racist police captain Hank Quinlan. From the very start of the scene, tension is underway; the very first thing shown to the viewer is an unidentified figure planting a time bomb in the back of a car. With the tick-tick of the bomb providing a demonic metronome, the audience is forced to sit on the edge of their seats throughout the scene, waiting for relief from the ungodly suspense of who is going to bite the dust. The nature of the scene being a long shot, where attention is explicitly called to its continuity, heightens the suspense of the proceedings. This long take demonstrates that shot duration can be as important to imaging as the more common mise-en-scène elements of framing or lighting; the unique rhythm of the shot provides a stark counterpoint to most other films of the era and instantly cue the audience into the strangeness and, more importantly, the brokenness of the film's world they are about to see. With this one fluid motion, Welles manages to introduce the main characters of the film as well as their problems. As with Kane, he understood from his extensive theater background that leaving the camera running without cutting away made the audience feel like they were flies on the wall, like they were in the room with the characters.

Touch of Evil also has many notable uses of low-angle shots throughout. One of the most famed elements of the picture (and Welles’s oeuvre), the technique is used to provide a psychological effect while looking stylish: to make the subject of the shot look strong and powerful in a manner not possible with a typical eye-line shot. While filming Kane, Welles couldn’t get the camera low enough for his liking so he actually made holes in the set’s floors. The psychological trick also served as a means to show the set’s ceilings on-camera, a rarity in Golden Age Hollywood fare, in order to add more realism to the picture. In Touch of Evil, the intent of low-angle shots is mostly to further cue the audience into the jagged, morally crooked characters at the film’s core. Thus the main antagonist of the film, brutish, ogre-like Hank Quinlan, is seen from below for much of the film’s runtime; hulking over the camera, the audience is clued into Quinlan’s level of power and the evilness imbued within him. It isn’t until the character falls off the wagon after 12 years of sobriety that he is depicted in a less domineering light, from above, to demonstrate both his weakness at the hand of the drink and the loss of power he now suffers as a result of Vargas’s probe into his corrupt policing practices. Other examples of low-angle shots are peppered throughout the picture, most notably with regards to the family members of “Uncle” Joe Grandi, the (likely criminal) brother of a man Vargas has recently had locked up for drug charges. Both as a sign of his newfound allegiance with Quinlan and also as a vehicle to enact steely vengeance of his own, the psychotic Grandi has his family terrorize Vargas’s wife, Susie, at the motel she is staying at (that he also owns). To demonstrate the group’s collective power over lone Susie, the group of toughs are consistently shown from below, giving them an imposing nature that is undeniably wicked. When the threatening individuals finally advance upon helpless Susie in her bedroom fortress, a potent mixture of low shots and abrupt cuts are used to highlight the chaos and pure terror underlining the proceedings; the perspective becomes that of fear-laden Susie’s.

Another cinematic technique somewhat ubiquitous with the film is Welles’s use of deep focus, a type of shot where the foreground, middle ground, and background are all readily visible. Creating a rich depth of field, Welles uses these shots throughout the film to pay respect to natural time and space. Perhaps the most notable example in this film is a famous scene in Sanchez’s apartment. Married to the daughter of one of the victims of the detonation that opens the film, the young Mexican Sanchez is ultimately framed for the murder by Quinlan and his American policing associates due to their planting of dynamite sticks in the former’s bathroom -- a fact not unnoticed by Vargas. In the scene in question (a 5-minute long shot in itself), Sanchez is being roughly interrogated in his apartment by the American officers, with Vargas looking on in dismay and acting as Sanchez’s lone defender. For much of the shot, the camera does its absolute damndest to keep all figures in the frame, both those relevant and those seemingly irrelevant. This can be attributed to the wide-angle lens employed by Welles, which encourages a much greater depth of field than the commonly used telephoto lens of the era and enables individuals to loom in the shot in a somewhat disquieting manner. In this example, up to 7 different players can be viewed at the same time in the tight apartment setting (noted by Welles to purposely create a sense of claustrophobia): Vargas, Quinlan, Sanchez, Grandi and various American police officers. Each individual’s gaze and expression can be registered, forming a rich visual tapestry for the audience. The nature of such a wide field, accompanied by the overlapping dialogue (another staple of the film, previously utilized in Citizen Kane), forms a disorienting image that is also inherently naturalistic. Through the looking glass, this hellish, corrupt world more closely resembles ours.

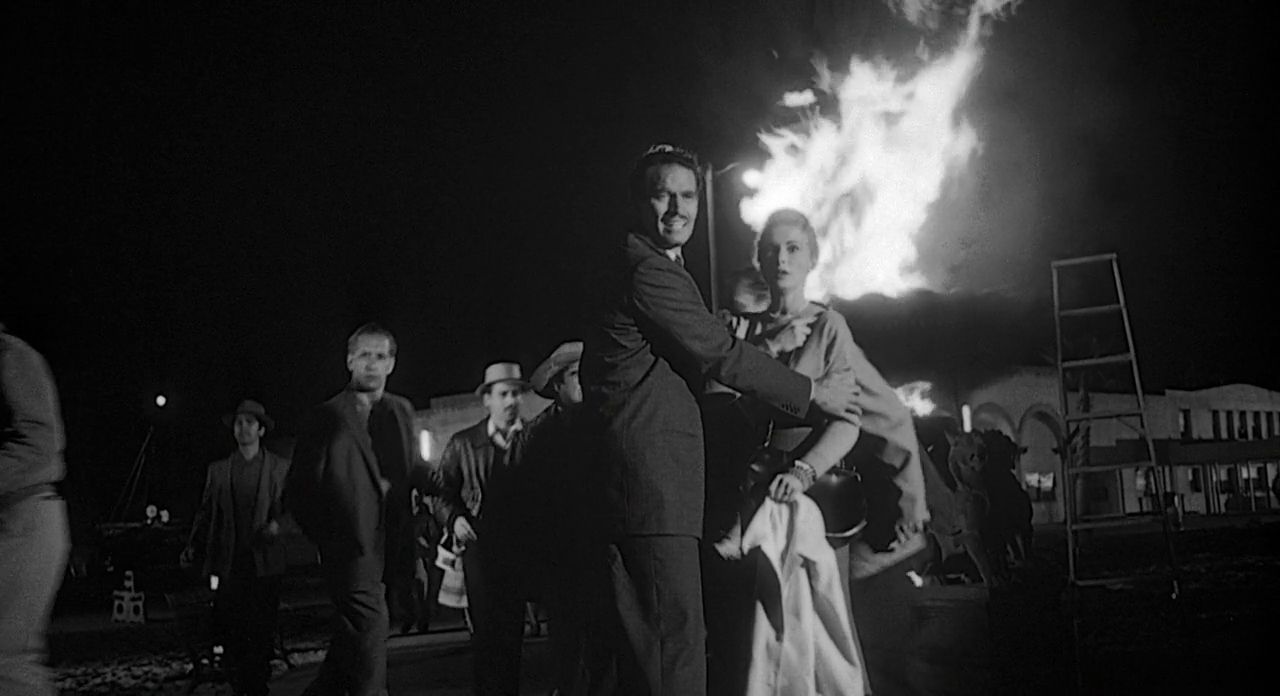

The film also touts many camera compositions that can be described as less than naturalistic, instead tipping their hat in favor of avant-garde German Expressionism. The aforementioned scene in which Susie is terrorized by Grandi’s relatives is one example, where the camera is fueled by pure nervous energy, launching through a menagerie of extreme closeups and funhouse tilts. Yet, in a picture in which almost every shot is off-kilter to a degree, there is one in particular that takes the cake: the final climax. In this tense scene, in which Vargas is shown trailing a drunk Quinlan outside with a tape recorder to acquire a confession, nothing makes any natural sense. The landscape is shown from a variety of eccentric angles: from high above, from below, and especially from the side, the number of degrees the camera is tilted to almost seeming purely random. Greatly distorted closeups of Vargas, provided by the wide-angle lens, are also strewn throughout. The sequence becomes an almost carnivalesque blur, a hallucinatory mirage of haphazard imagery. Sometimes the camera is on Vargas, sometimes it’s on Quinlan and his partner, Menzies, and other times it’s on neither. While this sounds innocuous, it is the order of shots that is confounding, serving to disorient the viewer and make them question the true makeup of the scenery they are viewing. The scene works quite well in that regard, trying to win an emotional response from the audience; in this case, discombobulation accompanied by fear that Vargas will wreck his final chance for clearing his name and evil will win out.

Touch of Evil is today rightly heralded in film scholar circles as a cinematic tour de force, one that peppers the previously defined conventions of film noir with elements of experimentalism that almost render it a different beast entirely: proto psychological horror at points. Yet despite this, the film receives nary a quarter of the attention and praise heaped upon Welles’s earlier Citizen Kane, in spite of the fact that Touch of Evil turns the cinematographic dials from that movie up to 11 and produces an effect much different from that picture’s reflective character study. Perhaps it’s first-is-best syndrome; the fact that the equally-well-constructed Touch of Evil had to follow that opening act; but, undoubtedly, Touch of Evil deserves acknowledgment for its role in establishing a cutting-edge form of film noir. It’s as terrifying as Hitchcock at his peak, and it manages to adeptly join both the commercial (the thrills) and the noncommercial (the esoteric camera techniques) into a picture that can be enjoyed both with popcorn or as a topic of study.