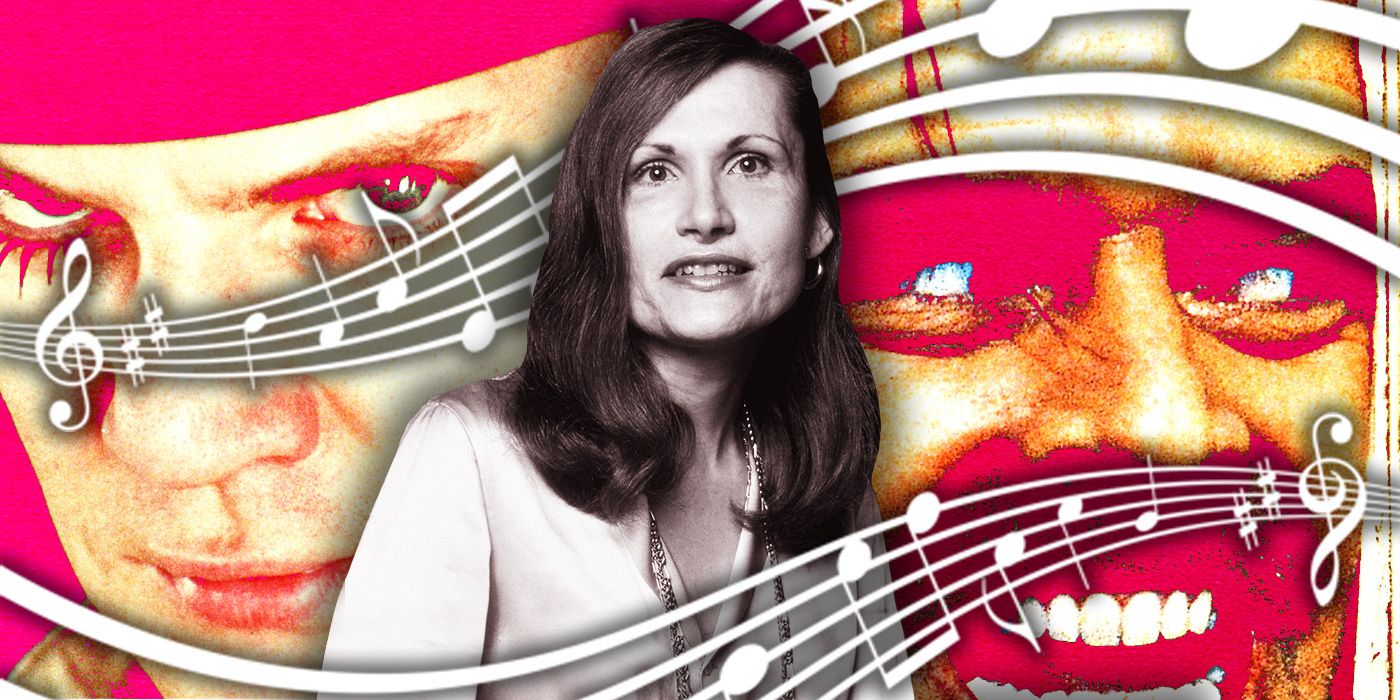

Wendy Carlos is a musician, physicist, and engineer best known for her work on the Moog synthesizer and the soundtracks for Tron, A Clockwork Orange, and The Shining. At times referred to as the “mother of the Moog”, she worked with Robert Moog (who she met while she was at college) to create her 1968 project "Switched-on Bach", and to develop the original commercially available Moog synthesizer. Although she only worked on three original soundtracks, her work has reached icon status and her influence is clear throughout contemporary scores. Let’s dig into what makes her work, and her collaborations, so special, and why she’s such an important figure in composing for the screen.

Early on in Carlos’ career, she created a series of re-imaginings of classical compositions on a modular synthesizer. The nature of the synthesizers she used meant that only one note could be played at a time, making this quite challenging. The outcome of this project was the album “Switched-On-Bach", released in 1968. Carlos’ intention, as mentioned in an interview with Carol Wright, with this album was to create something accessible on the early synth technology, as opposed to the dense, avant-garde music that was generally being created with modular synthesizers at the time. “Switched-On-Bach” led to the beginning of a long collaboration with producer and vocalist Rachel Elkind, who would prove to be fundamental to the creation of the score of the two Stanley Kubrick titles Carlos worked on: A Clockwork Orange and The Shining.

A Clockwork Orange was Carlos’ first foray into scoring for film. The soundtrack featured electronic renditions of classical compositions by Ludwig van Beethoven, particularly a number of his choral movements and scherzos. The use of relatively famous pieces creates an interesting effect in the context of the film’s soundtrack. Carlos’ score takes the familiar – Beethoven – and turns it into something unfamiliar and novel, with the use of an (at the time) uncommon instrument. This almost creates a sense of the “uncanny valley” effect, in musical form, meaning that it is almost human, but not as we know it or in a sense that we would recognize. Hearing something familiar being utilized in a new and inhuman way can be unsettling, making this the perfect soundtrack for a horror movie as disturbing as A Clockwork Orange.

The Moog synthesizer that Carlos works with functions by creating sound from scratch in the same sense that an acoustic instrument like a guitar would. However, the use of early acoustic technology in haunting ways doesn’t end with sound synthesis. Carlos also worked extensively with sampling in her scores. Namely, she and Elkind used an early version of a vocoder on the soundtrack for A Clockwork Orange. The vocoder technology made it possible to manipulate a sample of Elkind singing with mesmerizing effects. This interplay between the human and inhuman, the expected and unexpected, is all a part of what makes Carlos’ scores not only so incredibly special but also so deeply haunting at times.

Her two soundtracks for Kubrick both featured the use of ambient sounds as samples, borrowing from a French technique of music-making called "musique concrète". This really allows the scores she creates to capture a feeling perfectly, by creating a full scene sonically. While this technique is, of course, not limited to Carlos’ works (other composers such as Hans Zimmer have also used the practice), she was a fairly early adopter of the technique in film scoring. What else is interesting is that her soundtrack for Tron did not make use of ambient samples. This means that when creating these three-dimensional soundscapes, her vision was specifically focussed on her idea of how a horror film, or perhaps, these stories, in particular, should sound.

Her influence on later soundtracks is easy to track, too. From The X-Files‘ classic opening (Mark Snow) to Stranger Things’ eerie synthwave retro-stylings (Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein), Carlos’ synth sounds seem to echo everywhere. There are more direct examples of her influence, too. In 2010, French musicians, Daft Punk, released their version of her original score for Tron track-by-track for Tron: Legacy. Her impact isn’t limited to film and TV scores, either. Without her work on developing a commercially viable version of the Moog synthesizer, it’s likely that contemporary rock and pop music wouldn’t be the same either. Not only has that specific synthesizer been adopted by so many musicians across a variety of genres, but it has also been developed into different models numerous times since, reaching new audiences each time. It’s amazing to think of the “butterfly effect” those recreations of classical compositions and a handful of movie scores have had across popular culture.

The worlds Carlos creates in her scores are vivid and all-encompassing even when listened to on their own, pulling the listener into a world of her own sonic creation. When paired with equally gripping movies, it’s a match made in heaven. This element of collaboration when creating a film score is magical. The filmmaker creates a visual world to invite the viewer into, and the composer makes an auditory world to go with it. Carlos is no exception to this rule. Her work greatly enhances the fictional worlds that it touches. Can you imagine The Shining without the ominous drones of Carlos’ Moog? A lot of the beauty of her work lies in other wonderful collaborations too. No woman is an island: from Elkind’s hands-on production style and vocal contributions to Carlos co-developing Moog’s eponymous synthesizer, it’s easy to see that Carlos’ magic may not have happened in the same way without these creative partnerships.

Both Carlos and Elkind together have had an immeasurable impact on composition for the screen. They also both broke down social barriers, as well as musical and acoustic ones. Even today, there is a substantiated gender gap in film composers in the US. As of 2020, only around 5% of composers in Hollywood are women, according to media researcher José Gabriel Navarro. Furthermore, in an interview with Arthur Bell for Playboy in 1979, Carlos came out publicly as a transgender woman, with Elkind as her ally and supporter in making this statement. The scores Carlos and Elkind created together and the influence the two women have had on scoring, alongside their powerful working and interpersonal relationship, are truly vital pieces of social history – for women’s history, black history, and LGBTQIA+ history. There are other amazing women who pioneered composition and electronic music at the time – Laurie Spiegel and Daphne Oram to name a couple - and other immensely talented women have developed the field since, such as SOPHIE, Pamela Z, Gavilán Rayna Russom, and Nancy Whang, and every story is vitally important in breaking the glass ceiling in composition and sound design.

While Carlos is far from being the only composer who has made excellent use of synthesizers, created classically-informed scores, and built exceptional soundscapes throughout the years, it’s remarkable how her legacy has shaped the climate of music for film since her work began in the 1960s and ‘70s. Carlos is regularly referred to as a pioneer, and it’s a label that is well-deserved. Her songs often play with pre-existing ideas or compositions, transforming them into something entirely innovative and ground-breaking with her own personal musical signatures and inventions in acoustic science. In a lot of ways, although her discography of scores is limited, it’s no surprise that her influence runs so deep through original movie soundtracks, popular music, and overall musical innovation.