In a 1999 BBC interview, musician and actor David Bowie was asked about his perspective on the future of an Internet that was growing out of its infancy. With a visible sense of awe, Bowie laid out to a skeptical interviewer that he believed society as we knew it was on the “cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying." When it came to the potential of how this new horizon was expanding before us, his prediction proved to be quite fortuitous as the Internet now both shapes the people who use it and, conversely, is shaped by us as well. Though he wouldn't have known it, Bowie’s statement also serves as a guiding thesis that is fulfilled by the new film We’re All Going to the World’s Fair in how it captures that beautiful combination of fear and freedom unlike anything else that has come before it.

Originally blowing audiences away at festivals like Sundance and North Bend in 2021, it is now getting a wide release starting on April 22. A debut feature from the imaginative writer-director Jane Schoenbrun, it takes us into the expansive world of the Internet with such precision that it is one of the most vibrant works of recent memory. Beyond that, it is one of the truest films about our online world in how it both channels and creates an emotional resonance grounded in its authenticity.

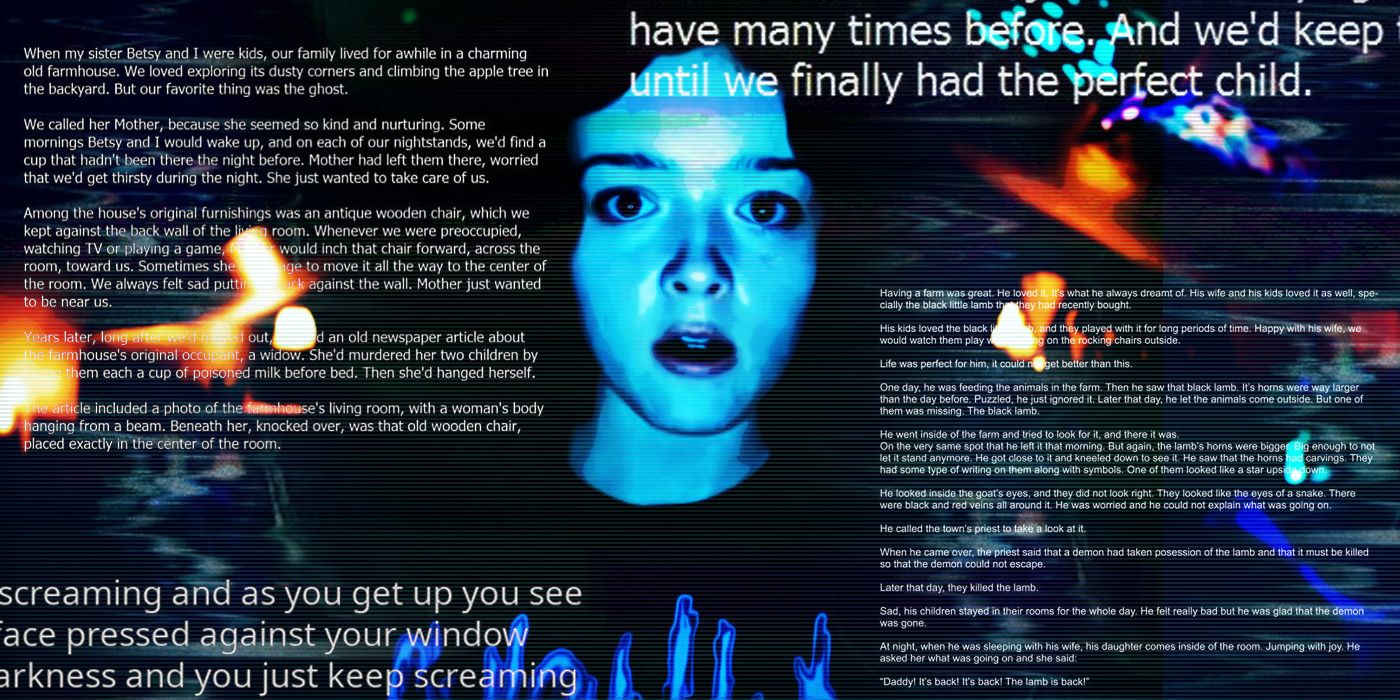

The film centers on young Casey, played with a remarkable sense of presence by first-time actor Anna Cobb. Playing entirely to the camera with almost no other actors to speak of, she operates in synchronicity with Schoenbrun’s vision of youth. Alone and without any broader sense of connection outside the narrow world of her attic bedroom, she turns to an online game that opens her mind to something beyond herself. Known as the "World's Fair Challenge," Casey dives into this world of “creepypasta” that starts to consume her every waking thought. For those unaware, creepypasta is essentially a catch-all term for horror stories that proliferate throughout the Internet. Driven by fascination, Casey believes that the game is beginning to impact her physical state and begins to capture this process via a series of videos. As she sinks further into the game and the promises of purpose that can be found within, the line between the online world versus the physical one is rendered inconsequential.

It is in this blurring of the lines between the Internet and ourselves that Schoenbrun has tapped into something profound. It is a film that confronts all the beauty and fear of its story in a manner that is wholly original while also being so thoroughly relatable that it lodges itself firmly in your subconscious. It begins with the small reference points of technology that go unspoken but become universal in how we use them to build our identities. There is the loop of videos autoplaying into nothingness, providing momentary comfort in the certainty that another respite is coming. The outside world provides no such assurances.

We hear the distinct sound of the counting down of Photo Booth, marking the final moments before you share yourself with the world at large. Inversely, there is the silence following the hanging up of a Skype call where you are left to look back at yourself and wonder what went wrong. These quiet moments may not seem all that groundbreaking, though it is precisely because of the simple accuracy it captures that they prove to be so impactful. They bring to life nuances that otherwise go ignored in favor of a spectacle that tries to preserve an illusive disconnect between us and the ever-present Internet to which we are inexorably tied.

Far too many films are made with the technology of the Internet held at a distance, creating fantastical approximations of the online world that become paper-thin when held up to the light. Think of the recent Ready Player One or Free Guy, both woefully shallow depictions of the online space despite how inundated they are with a litany of pop culture references that characters repeat ad nauseam. That is not the case for We’re All Going to the World’s Fair which breaks through superficial cinematic understandings of technology to find something deeper. Operating with a budget likely a fraction of such larger blockbusters, Schoenbrun still surpasses both with a commitment to exploring the imaginative potential to be found in the puzzling yet poetic way the Internet has become such an integral part of our lives.

As Casey posts videos as a growing visual diary of her days, we learn more about her through what she shares with the world. As she engages with this digital space, we see how she feels more at home in doing so than she does anywhere else. Schoenbrun delicately edits these videos together, stitching in the sadness that Casey is experiencing with little fanfare and a focus on the emotional state of being that underlies each of them. Notably, the videos all come with a view count that shows she is speaking to a small few that soon becomes an audience of one as the film shifts into uncertain territory. It conveys a desperation and hope for the possibility of connection that most other films fail to grapple with in any meaningful way.

When watching We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, one prevailing reference point that kept bouncing around my mind was Kiyoshi Kurosawa's outstanding 2001 film Pulse. An experience that begins as a horror film and shifts into becoming a gentle exploration of something more emotionally devastating, it was a pleasant surprise to hear it come up in an illuminating interview Schoenbrun did with The New Yorker Radio Hour. In said conversation, which is absolutely worth listening to in its entirety, they broke down how both their most recent work and Pulse “are films that are actually interrogating the emotional center of why [the Internet] exists and what we use it for.” Both films, rather than being woefully out of touch and off-target in their portrayal of the internet as many are, eschew easy categorization in favor of something more moving. There is no detachment from our humanity behind all the bells and whistles of this digital space. Both films do more to reveal how closely tied we are together than we initially realize we are when conceptualizing our relationship to the Internet. They are able to build an emotional and technological acuity, finding a sense of formal beauty even when wrapped in a prevailing sense of thematic isolation that knocks you flat.

When experiencing all the splendor of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, much can be gained in understanding how Schoenbrun’s own experience of growing up and exploring their identity through digital spaces informs the way the film engages with the Internet as a place of limitless potential. It is in this specificity that something simultaneously universal is found. Yes, universality can often be used as a cudgel against stories that are different from the mainstream. However, what makes this fit here is that Schoenbrun doesn’t ever compromise their vision in order to be palpable. Instead, they take us along with them and bring us into a world that finds familiarity in the unfamiliar.

You don’t need to be well-versed in creepypasta to know what it means to be lonely and find an outlet that keeps the dark thoughts at bay. The way the film draws you into the experience of Casey and the way she grows is only the beginning of how it captures something more comprehensive about the experience of the Internet. We experience the joy, uncertainty, terror, and eventual catharsis that can be found there. Like us, the Internet can be messy and complicated without always having a cohesive sense of order. This makes sense as we shape it and it shapes us, a symbiotic relationship that most films only scratch the surface of. That is, except for works like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair. It looks deeper to see a portrait of ourselves reflected back in the places where we spend most of our time and end up leaving our imprint on just as it does on us.