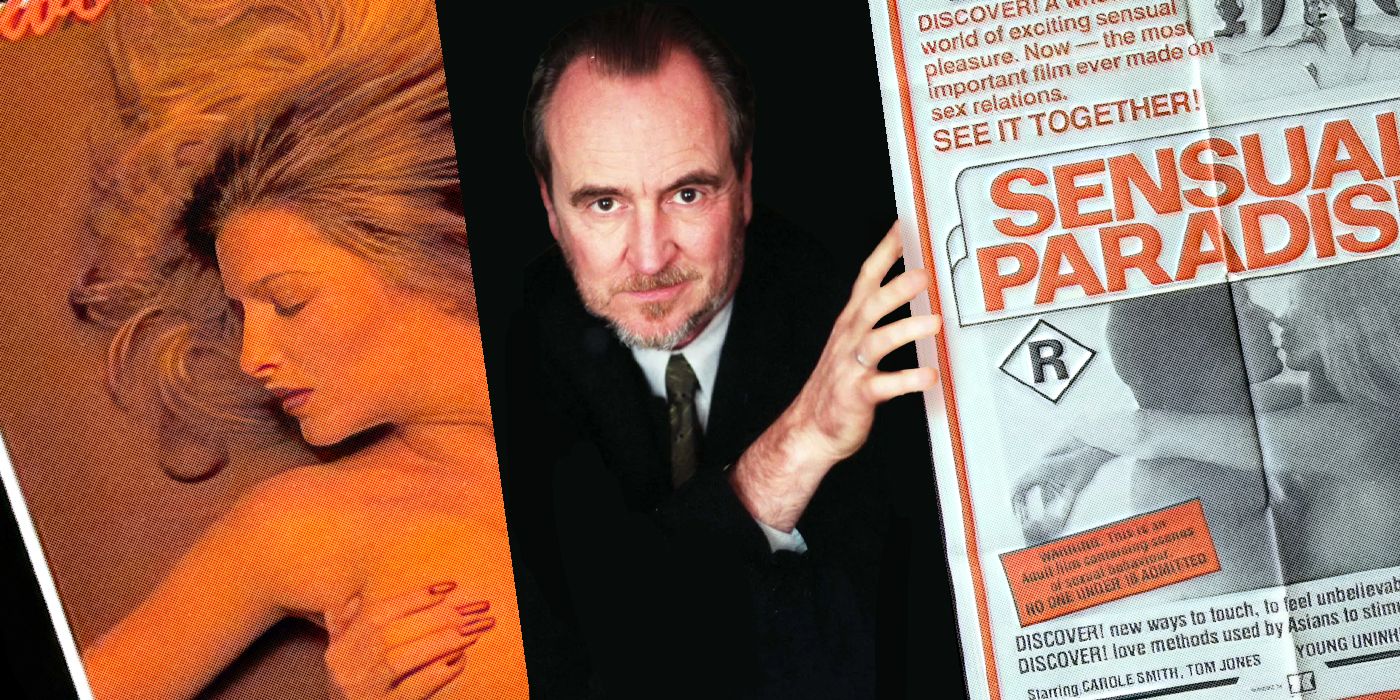

He could find his way into our minds and pull out the deepest fears and darkest secrets from our subconscious. He knew how to push the buttons that made us squirm in our seats and look at the movie screen between fingers that covered our faces. To paraphrase the famous tagline from Poltergeist, Wes Craven knew what scares us, and for more than four decades, the writer-producer-director put the baddest of our bad dreams on celluloid and made us all look over our shoulders as we left the movie theater and walked to the parking lot. The Halloween season can't go by without giving Craven his proper dues as a horror legend, but it may surprise some to learn that 47 years ago, Craven took a sojourn into the X-rated genre with The Fireworks Woman, a shocking and disturbing erotic film that could arguably be called a horror movie, as well. And although it was a hardcore film aimed primarily at the "raincoat crowd," looking at The Fireworks Woman today, it's easy to spot Craven's signature style in the movie, as well as glimpses of themes Craven would explore and patterns he would follow in the years to come.

Craven and the "Porno Chic" Era

There was a period of time from the early 1970s through the early 1980s that became known as the "golden age of adult films," when movies like 1972's Deep Throat and 1973's The Devil in Miss Jones ushered in an era that took X-rated fare from cheap peepshow "loops" to full-length features with well-developed plots, above average production values, and actors who could convincingly deliver dialogue, as well as...other types of performances. These movies often attracted a diverse range of audiences, including celebrities like Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who got the paparazzi's camera shutters clicking when she queued up to see Deep Throat in Times Square. Craven took advantage of this new wave, writing and directing The Fireworks Woman in 1975 (under the pseudonym Abe Snake), smack dab in the middle of the 70s "porno chic" decade and three years after the release of his first feature, the classic shocker The Last House on the Left. Even with The Last House on the Left, there was an X-rated connection. Fred J. Lincoln, who played Weasel, one of the crazed killers in the film, was also a prolific adult movie actor, producer, and director. Craven had already made connections in hardcore circles long before The Fireworks Woman, including producing two early 70s sexploitation films with Friday the 13th director and The Last House on the Left producer Sean S. Cunningham.

Although their stories are completely different, The Last House on the Left and The Fireworks Woman share a number of common themes, not to mention cinematic touches. Fans of Wes Craven know that his horror films often feature domestically tranquil settings, like quiet suburban neighborhoods, that are suddenly shaken by violent and bloody events. In The Last House on the Left, an upper middle class Connecticut home becomes a house of torture and carnage. In 1984's A Nightmare on Elm Street, a serene bedroom community is invaded by a monstrous killer, and in 1996's Scream, a sleepy Napa town houses a masked murderer. The Fireworks Woman is similar. Within the first few minutes of the film, Craven shows viewers lovely shots of a Cape Cod-like sunset landscape, red-shingled coastal houses, and a beautiful young couple, Angela and Peter (Jennifer Jordan and Eric Edwards), very much in love, frolicking along the shore. Craven then jars viewers, not with violence, but with the revelation that the young couple are actually brother and sister. And if that's not shocking enough, it's also soon revealed that the brother is a priest, which brings up two other familiar Craven themes - the subversion of religious conventions and the disruption of societal standards.

Early Shades of Freddy Krueger

It's no secret that Craven's strict Baptist upbringing - and the ultimate abandonment of his faith - greatly influenced his work. He saw a clear corelation between what his religion taught him and how he viewed horror, and he believed people were drawn to horror films to deal with fears they already harbored. "That's why we have concepts of heaven and salvation, because there is a sense of being lost, of being under threat," Craven said in an interview with Beliefnet. "We are, at our very basic...these very frail little vehicles." Nowhere is this view more pronounced than in The Fireworks Woman. For starters, Craven himself appears in the film as a kind of devil-like figure, frequently dressed in a top hat, vest, and tails, smoking a cigar, lurking in the background, and occasionally tempting the film's characters to venture down the darkest paths. Craven's devil, in fact, can even be considered an early prototype of Elm Street's Freddy Krueger - a hat-wearing menace inhabiting dreams, intent on pulling characters into a bleak abyss. The first scene in the movie features a macabre outdoor ritual, with dozens of nude people dancing in a meadow while waving sparklers in their hands, as Craven's satanic hellion stands among them, laughing maniacally while fireworks burst behind him.

The Mundane Becomes the Aberrant

Craven also had definite ideas about how he wanted The Fireworks Woman's characters portrayed. In a recent conversation with Collider, Eric Edwards, who played Peter, remembers being conflicted about taking on the character of a priest in love with his own sister. "I was uncomfortable. It was one of my more challenging roles, and Wes was one of the few who I got good direction from. He knew what he wanted to get out of me, and he got it." The film is rife with religious symbolism, include a dream sequence in which Peter stands nude on a boat floating in the water, arms outstretched in front of the sail, conjuring up images of Christ hanging from the cross. "I remember filming that scene," said Edwards. "It turned out to look really beautiful, almost ethereal, on film." This scene also resembles one from A Nightmare on Elm Street, when Freddy inhabits Tina's (Amanda Wyss) dream. Freddy stands before her, grotesquely exaggerated arms stretched out horizontally, but this time like a Satanic creature presenting a ghoulish depiction of the crucifixion.

Craven crafted some of his best stories out of the mundane becoming the aberrant. In The Fireworks Woman, Craven takes the concept of familial love and turns it upside down, not unlike what he did in The Last House on the Left. When a wholesome married couple finds out their daughter has been brutally murdered, they become crazed murderers themselves, slaying their daughter's killers in the most brutal ways. In 1977's The Hills Have Eyes, an entire family, including grandma, becomes gun toting, knife wielding executioners of a frenzied clan of ravenous desert mutants. In Elm Street, it's revealed that all the law-abiding parents in the neighborhood set Freddy Krueger on fire after he was unjustly exonerated for a string of child murders.

And while The Fireworks Woman avoids the bloody violence of these other films, Craven dares audiences to accept two protagonists involved in an incestuous relationship. Peter, racked with guilt over his feelings for Angela, flees back to the seminary while Angela goes to work as a maid for a wealthy woman and her gentleman friend, hoping to start fresh without Peter in her life. Unfortunately, Angela becomes a sexual plaything for the couple, nothing more than a tormented victim, and this is where elements of horror creep into the film. In her quest to find her own footing as a woman, Angela is continually used and abused by virtually everyone she encounters, and Craven directs many of the hardcore scenes in the film with little eroticism, accompanied by eerie, foreboding music. It's as if Craven wanted audiences to reject any notion that what they were seeing on screen was romantic, passionate, or even consensual. Angela becomes trapped in a nightmare from which she can't awaken, much like the victims in Craven's Elm Street movies.

The Purveyance of Religious Symbolism

Angela continues to return to Peter at the seminary looking for solace, but Peter rejects her as she becomes increasingly disconnected from reality. "Consciousness seemed to grow lighter and lighter until I simply floated away from my body," Angela says during one of her reveries (and once again conjuring up images of the Elm Street nightmare sequences). In a particularly creepy and diabolical scene, Craven, as the devilish figure (this time not dressed in his signature top hat and tails), suddenly appears out of nowhere next to Angela and tells her, "There are no mysteries that can't be untied, no fights that can't be won. But it'll cost you something. You know what I mean?" Satan is bidding Angela to sell her soul in order to end Peter's rejection. And in keeping with Craven's expression of the struggle between religion and hedonism, goodness versus iniquity, he immediately follows this scene with one between Peter and his pastor, with the pastor virtually echoing Craven's devil's words, but this time in the context of righteousness. "Leave it to God," the pastor says to Peter. "There are no mysteries he can't unravel, no fights he cannot win, no matter who the adversary might be." Craven presents the line between good and evil as thin and easily traversed, and in doing so, leaves audiences wondering if Angela selling her soul will bring her redemption or destruction. This is a moral dilemma Craven revisited in his other films: will going outside societal norms and mores (like townspeople murdering Freddy or parents slaying their daughter's killers) ultimately bring healing, or will it cause the ultimate downfall? Craven leaves no easy answers, and it's up to audiences to contemplate the rewards and consequences.

The Fireworks Woman is not an easy watch, and not just because of its hardcore elements. One of Craven's greatest strengths as a director was his ability to push the filmmaking envelope and make audiences uncomfortable, whether through graphic violence, disturbing imagery, or taboo subject matter. The Fireworks Woman is an early example of a Craven film that offers a glimpse into a future where he would continue to test the limits. There's a line in The Fireworks Woman that could easily describe Craven's filmmaking vision: "Boredom will kill you faster than the bullet." No one can ever say Craven's movies left audiences bored.