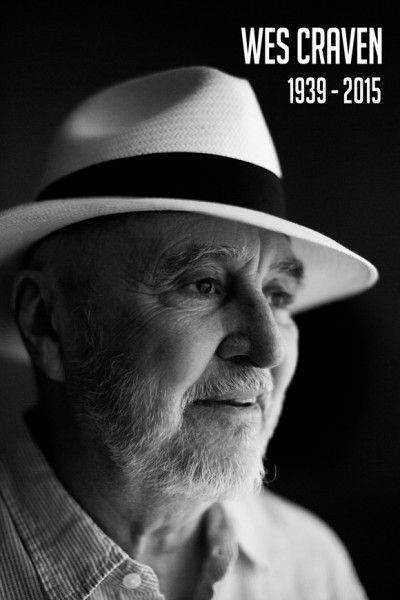

On Sunday night, legendary horror director Wes Craven passed away at the age of 76. It's a huge loss to the film community, a devastating loss to the genre community, and a loss that feels personal to a lot of us – even those of us who never met the man. But that's the kind of filmmaker Craven was. He made seminal films. Films that felt personal. Film's that are so ingrained in our cultural makeup they feel a part of us.

I owe my love of horror – a love that has become an essential part of my identity -- to Wes Craven. The first horror film I ever saw was A Nightmare on Elm Street: Dream Warriors. The first horror movie I ever loved was Scream. In every way, he was my shepherd into the genre. Without him, there is no me as I am today. That sounds like a crazy thing to say about a person you never met, but it’s true. Judging by the reactions I saw online yesterday, I’d bet it's true for a lot of you too.

You probably know his history. It's kinda kooky. Raised in a fundamentalist Baptist household, Craven’s puritanical mother sheltered him from the sex, violence, and profanity of cinema. Only Disney cartoons were allowed in the house. Craven earned a masters degree in Philosophy and Writing at Johns Hopkins, which led to a gig as a humanities professor at Clarkson University. There, he first discovered his love of movies when he helped some students create a James Bond spoof. Filmmaking became his passion, and when that passion led to hard financial times, Craven took a job writing and editing porn films. There, he met Sean Cunningham (the very same who would go on to create Friday the 13th), a fellow young pornographer with a mission to make a nasty, bloody horror film.

That film would become 1972’s Last House on the Left. A scathing, brutal twist on Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, detailing a family’s revenge on the band of criminals that raped and murdered their daughter. Craven’s directorial debut was such a grating, perverse film that it became an instant source of outrage in the critical community, suffered a lengthy ban in the U.K., and remains a controversial film to this day. But like all of his best work, Last House wasn’t just a graphic display of barbarism for entertainment’s sake, but a film that had something to say about the society from which it emerged. Craven had no idea how to make a horror movie, but he had a purpose behind it, and it made for a draining, sickening movie-going experience.

But Craven didn’t want you to enjoy yourself while you watched Last House on the Left. Disturbed by the media coverage of Vietnam, he wanted to make movies that were honest about the impact of violence. No titillation, no escapism, just the bald consequences of the harm humans inflict on each other. If the bumbling cops offer any comedic relief, it is slight, knowing that every moment they fail at their job, the young girls are being tortured and murdered. His second film, the classic The Hills Have Eyes, was another revenge piece about a suburban family, following the surviving members as they hunt down the gang of backwoods cannibals that decimate their family. It, too, was defined by that same ferocious brutality that characterized Last House on the Left; a confrontational but contemplative film that challenged the audience to keep watching. It dared the audience to acknowledge and own up to the horrors of humankind that surface when we strip away the protective gauze of civilization.

After a string of lesser achievements (Deadly Blessing, Swamp Thing, The Hills have Eyes II) Craven finally made a commercial success with his mega-hit, A Nightmare on Elm Street, which ushered in a new psychedelic phase in Craven’s career. Nightmare reinvented the slasher for an audience weary of silent masked men stalking trembling blondes. His iconic creation, Freddy Krueger, was a new kind of slasher villain with a wicked sense of humor; a grinning maniac who wasn’t just evil, but who reveled in it. For all the surreal gags and dreamscapes, A Nightmare on Elm Street returned to Craven’s tried and true themes -- the cyclical nature of revenge, the sinister element just beneath the veneer of the domestic, and as always, the price we pay for violence.

Even in his most surreal films, which include the voodoo zombie thriller The Serpent and the Rainbow, Craven remained focused on the human element. Freddy Krueger is an iconic monster, but the film (and the sequels Craven participated in) pays most loving attention to Nancy, the heroine of the piece. Another one of his wonderful qualities as a filmmaker -- Craven was unusually good to women in a genre that treated female characters like extraneous, fleshy props. Or, even in best case scenarios like John Carpenter’s Halloween, treated only the incredibly pure, inoffensive, and domestic Laurie as a character worthy of respect. At the end of Nightmare, there’s no all-knowing "Ahab" (a la Dr. Loomis) to save Nancy’s day. Instead the “patriarchal figure”, her father, fails to show up, and Nancy fends for herself, turning the domestic landscape of her home into a war zone.

Indeed, it was these genre formulas and genderist constructs that Craven sought to upend during his meta phase, which started with 1994’s unacceptably underrated New Nightmare, and culminated in 1996’s Scream -- the razor sharp and self-aware slasher that redefined the genre for an entire generation. My generation. As I’m sure is true for many who fall into that category, Scream was my first proper Craven film, and it was love at first sight.

Here’s a brief recap of my whirlwind romance with Scream: I used to spend one week of every summer idling about with my cousin for days of movie marathons, video games, and general laziness. The summer of '97 was nothing but a laserdisc of Scream, watched ad nauseum for a week straight. By the weekend, we knew every line. Verbatim. When it was time to take my cousin home, we recited the entire movie, line-for-line, for the entirety the two-hour drive -- much to the chagrin of my annoyed, but patient father. “Don’t you guys want to listen to the radio?" He asked. "No!" we shouted out between our best Ghostface impressions. We didn’t just play act the scenes because we were kids and it was fun (although we were and it was), but because they made us feel powerful. “Not in my movie!” we shouted, blasting finger guns at an imagined assailant. It was a rare opportunity where we got to feel like the hero of the piece. Upon reflection, I realize we only ever playacted the stuff that made us feel powerful -- Xena, Buffy, Scream – we craved archetypes we could relate to. We wanted to play cops and robbers using characters we could identify with.

Craven offered no shortage of tough female characters (even Tatum, the hot best friend who would have been nothing but a ticking clock with bewbs in a lesser film, was a well-drawn character with sass to spare), and so Scream became a movie that made me love movies. It was challenging, clever, and earnest despite all its on-the-nose self-referential meta-speak. There was a heart to it. And he populated it with characters rather than a body count. I mean, the bodies stacked up, but they were the bodies of characters you cared about. The stunning opening sequence of Scream is a microcosm of Craven's gift for good characters. Within moments he took a character you barely knew – Drew Barrymore's Casey Becker -- and turned her into somebody you cared about. Minutes later he turned her into somebody you mourned.

Craven displayed a unique sympathy for his villains, too. They were drawn from the ills of society and, thanks to his philosophy roots, the inherent ills of man. But Craven's sympathetic lens prevented him from becoming a nihilistic filmmaker. Yes, Krug and his criminal family are reprehensible, and yes, Pluto and his cannibal family are abhorrent, but Craven made sure you could empathize with them. He made sure you could feel the circumstances that created them and understood that violence doesn't just cost the victims, but the perpetrators as well. Because if Krug and Pluto were condemned, so too were the Collingwoods and the Carters who exacted their bloody vengeance.

Craven began as a pornographer and a teacher. I believe he stayed both of those things throughout his career, using each talent to bolster the other. He delighted, or sometimes disgusted, the audience with his understanding and fascination for the taboo. He had the pornographer's gift for putting nasty, no-good, forbidden things on film, and he used that skill to explore his favorite themes -- the darkness within, the sins of the father, the cost of a violent act. In turn, he used his skills as a teacher to inform the audience about themselves.

If his films seemed ahead of their time, it’s only because Craven helped inspire and create the genre trends that would dominate the landscape until he turned out his next visionary film, which would revitalize the genresphere all over again. He revolutionized the genre, not once, but three times, ushering in new trends only so he could upend them in a few years time. With each new masterstroke, Craven subverted the tropes so deftly that he created new ones in their place.

Wes Craven gave us nightmares. He gave us the post-modern slasher. He gave us Johnny Depp. He gave us Freddy and Ghostface, two of the most iconic horror villains of all time. He gave us mirrors that allowed us to see the darkest and strongest parts of ourselves. But to end this in a place of personal gratitude, he gave me the gift of a genre. My love of sci-fi is thanks to my father. My love for fantasy is thanks to J.K. Rowling. My love for horror – a love that has led to awesome jobs, even better parties, and some of my most enduring friendships – is thanks to Wes Craven. It's a gift you can't put a price tag on. It's a gift you can never properly say thank you for. I'll always regret that I never had the chance to thank him in person, so instead I can only give those thanks here.

Thank you for everything, Mr. Craven. Your absence will be felt.