In the upper echelons of cinema, there exists a prestigious group of films so highly regarded by critics that to find even the tiniest amount of fault with them is enough to be expelled from their elite circles forever. Citizen Kane, Vertigo, The Godfather, 2001: A Space Odyssey… all films that have received such levels of acclaim it is now taken as given that anyone interested in cinema will refer to them as masterpieces with zero hesitation. Of course, both of those statements are a little hyperbolic, but there’s no denying that their place in the history books is so firmly established at this point that it might as well have been decided by Socrates himself.

Another film in this esteemed tier is Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s psychological epic that is now commonly regarded as the greatest Vietnam War film ever made. Its story (a recontextualized version of the classic 1899 novella Heart of Darkness) follows Captain Benjamin Willard (Martin Sheen) as he is sent on a perilous journey to assassinate the rogue Colonel Walter Kurtz (Marlon Brando), all of which serves as the backdrop for Coppola to ruminate on the nature of war and the conflict between good and evil. It’s one of the most studied and analyzed films ever made, a staple on greatest films of all time lists, and served as the perfect closer to Coppola’s astonishing body of work in the 1970s. Even after forty-three years, its reputation continues to grow, and given the copious amounts of material written about the film since its release, one can’t help but wonder what else there is left to discuss.

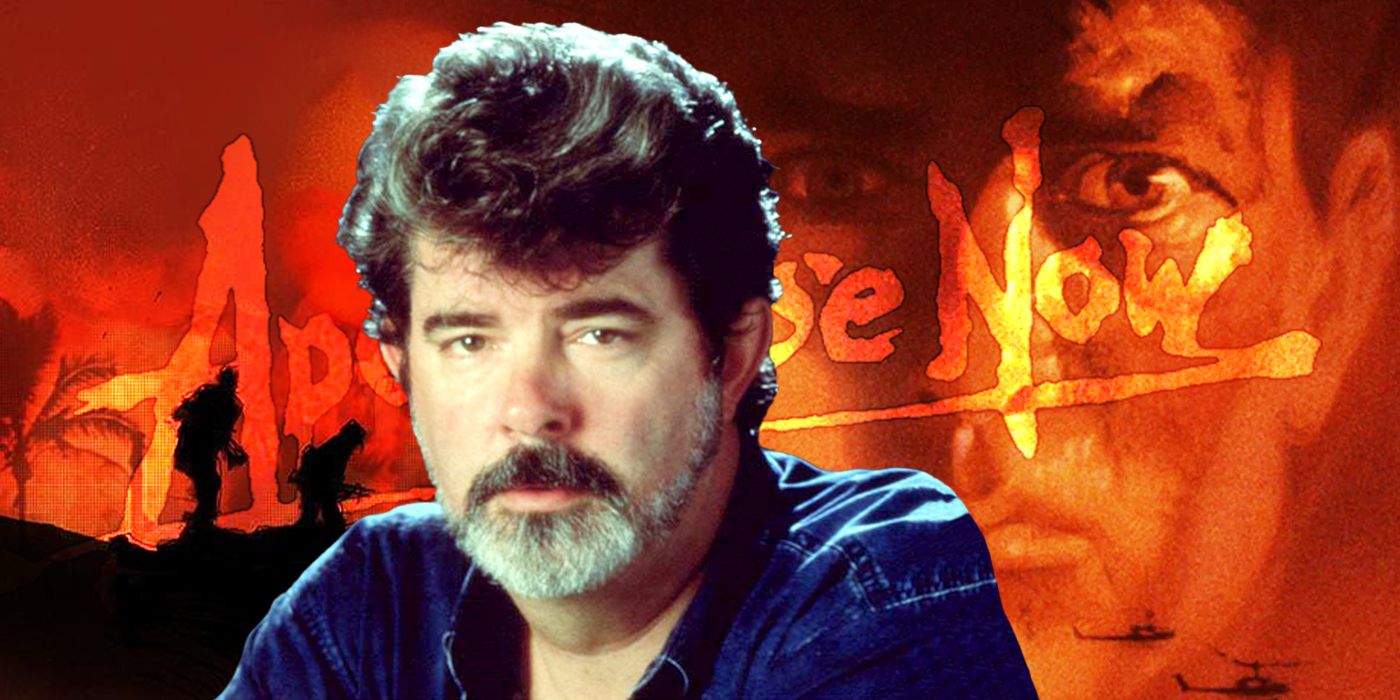

There is a curious piece of trivia related to its turbulent journey to the big screen, and not one related to its chaotic year-long shoot that has since become the stuff of film infamy (as covered in the excellent documentary Hearts of Darkness). Rather it pertains to the original choice of director, none other than outsider maverick turned Hollywood mogul George Lucas. While Coppola was always involved in a producer capacity, and had personally hired John Milius to write the script after working with him on The Rain People, Lucas had been the intended choice for director throughout much of its development. He worked on the project for four years, juggling it alongside early scripts for American Graffiti and Star Wars. However, it soon became clear that his schedule would not accommodate another experimental behemoth that would forever change the landscape of cinema, leading to Coppola taking over the project. By the time Apocalypse Now was released in 1979, Lucas’s name ranked amongst the most recognizable in the industry, with the pending release of The Empire Strikes Back ready to solidify him as one of the most powerful, too. How different cinema would have been had he opted to stick with the grim bloodshed of the Vietnam War is a question no one can answer, but speculating about his version of Apocalypse Now is a much easier task. It’s impossible to know if he would have achieved the unthinkable and made a better film than Coppola, but as with every film Lucas is attached to, there’s no doubt it would have made for an interesting experience.

But first, a little backstory. The late 1960s was a time of much change for American cinema. The first graduates of film schools were beginning to make their mark on the industry, and with it, they were bringing a new style of filmmaking influenced by the diverse range of global cinema. Their desire to experiment with the medium put them at odds with the Hollywood establishment, who had enjoyed decades of unopposed power thanks to the supremacy of the studio system. While films like Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider had signaled a change in the way Hollywood operated, progress was not happening quick enough for some.

Enter Coppola and Lucas, who decided to break away from the corporate web of Los Angeles in 1969 to form American Zoetrope, a production company that aimed to breathe new life into the industry. Both were graduates of the University of Southern California, and both had already collaborated the previous year when Lucas had directed a behind-the-scenes documentary about Coppola’s The Rain People, making further collaborations between the two a no-brainer. Over the next few years the two formed a close partnership, with Coppola serving as producer on Lucas’s debut feature THX 1138 and American Graffiti. While Lucas would gradually lessen his involvement with American Zoetrope as he focused on his own production company Lucasfilm, his time there helped pave the way for some of the greatest and most influential films of their era, while also marking his first step on the journey to Hollywood stardom.

His involvement with Apocalypse Now came about during this period, with John Milius approaching Lucas about directing his script in 1969. While Coppola would make numerous revisions to the script when he eventually took control of the project (most notably with a completely reworked ending), Milius’ draft largely adhered to the structure seen in the final film, making Lucas’ proposed version a fascinatingly unique way of telling the same story. Coppola’s work on Apocalypse Now is some of the most famous in cinematic history, and gave Willard’s journey the appearance of taking place in a psychedelic fever dream punctuated by a hallucinatory haze of burning palm trees and constant rainfall. Lucas, in stark contrast, had intended to take a minimalistic touch with the material, favoring a style of filmmaking called cinéma vérité. It’s a technique Lucas had previously employed in his early student films, weaponizing its stripped-back approach that removes artifice from the equation to give the impression that what the viewer is seeing is the stone-cold truth. Nothing more, nothing less. Anything resembling embellishment or Hollywood gloss is stamped out with an iron fist, allowing filmmakers to cut to the heart of their story. It’s commonplace in documentaries, but considerably less so in narrative films (especially ones with the scope of Apocalypse Now), but that wasn’t about to stop Lucas from trying.

The idea of shooting Apocalypse Now in a pseudo-documentary style, utilizing 16mm cameras in an entirely handheld format that evokes the feel of a newsreel rather than a film, is a prospect that raised many eyebrows, not least because the Vietnam War was still ongoing while all of this was being discussed. Lucas had originally intended to begin filming in 1971 following the completion of THX 1138, and had already enlisted his close friend and producing partner Gary Kurtz to scout locations. While Lucas planned to shoot most of the film in the Philippines, he also wanted to dispatch a second unit to Vietnam to capture footage of the actual war which would be intercut with the rest of the film. If his intention was to drag his audience kicking and screaming into the horrors of one of the 20th century’s most bloody conflicts, there is little doubt this approach would have achieved that.

Thinking about his decision conjures images of The Green Berets, a film released only a few years prior that stared the ultimate icon of American cinema himself, John Wayne. Its attempt to simplify the complexities of the most defining issue to face America since the Second World War into a story that was little more than a retread of the "cowboys vs Indians" trope (something that had long since fallen out of fashion) led to it being laughed out of movie theaters by critics, with its blind loyalty to American patriotism gravely misjudging the mood of the country. However, its subsequent success at the box office and lack of competition in the Vietnam War subgenre led to it becoming the most notable film on the subject for some time, a fact that no doubt influenced Lucas’ approach to Apocalypse Now.

His desire to adapt Milius’ script in a way that would make the audience forget they were even watching a film, providing a faithful representation of the conflict that avoided boiling things down to just ‘America good, Viet Cong bad,’ feels like a deliberate reaction to The Green Berets. Cinéma vérité’s sole concern is to the truth, a notion that The Green Berets ignored, and by presenting Apocalypse Now in a pared-down style that lacked the clichés of a typical war film, Lucas would have been able to avoid the pitfalls that Wayne’s film fell into. Even Coppola’s version, while far more nuanced a tale than what Wayne produced, still likes to linger on picturesque cinematography and complex action sequences that idealizes the spectacle that Hollywood is known for. Lucas’ version would have had none of this, and not just because its minuscule budget of just $2 million would not have allowed for it. Many action sequences would have been taken straight from the war itself, footage that would have rebelled against the notion that scenes of gunfire and explosions are primarily made to entertain. This would have compounded the anti-war sentiment of the story, leading to a film that, while not as technically proficient as Coppola’s version, could well have topped its emotional impact.

Not surprisingly, the idea of sending a crew into a real-life war zone proved a tad concerning for some involved, a feeling accentuated by Lucas’ desire to give the film a comedic edge. Kurtz compared its tone to M*A*S*H, a successful film and television series whose use of black comedy had served as a false veneer with which to provide a bitter commentary on the Korean War. While it’s unknown how much comedy Lucas intended to use, the very notion of using humor in relation to such a controversial subject would have been shocking for audiences of the time. However, it also would have served to ease the viewer into the film more efficiently, opening the door for a conversation that many people might have otherwise avoided. Thankfully hindsight is 20/20, and given Lucas’ abysmal use of comedy in his future works (most obviously the Star Wars prequels), it’s perhaps for the best that this idea did not make it into the final result.

Concerns about Lucas’ approach led to the film stalling in development hell, during which time Lucas moved forward with his more straightforward American Graffiti. Its success led straight into Star Wars, and while Lucas debated returning to Apocalypse Now following the completion of his sci-fi epic, ultimately Coppola took over as director. While that brought an end to Lucas’ direct involvement with the film, he still proved instrumental in getting it made after providing some much-needed funding during its lengthy time spent in the editing room. How differently Apocalypse Now would have been received had Lucas realized his version is something we will never know, but undoubtedly it would have had staggering ramifications for the industry as a whole had it been made over American Graffiti and Star Wars.

As it stands the version we got can count itself amongst the pantheon of the all-time greats, an accolade that will leave few critics ruminating about its other potential forms. But Lucas’ version looked set to be a brave and valiant attempt at portraying the atrocities of the Vietnam War in as close of a proximation to reality as was possible, providing an experience that may have cut a little too close to the truth for some. How he would have fared recounting Willard’s descent into madness in his odyssey to assassinate Colonel Kurtz will forever be a mystery, but there’s no doubt that it would have been a million miles from what we eventually got.