There's one scene in the second volume of ABC's LGBT rights miniseries When We Rise that speaks to the challenges of not only being a political activist with intentions toward a social life, but also attempting to summarize a political movement in a single and singular work. Gay activist and burgeoning political figure Cleve Jones (Austin P. McKenzie) is sitting on a desk with fellow activist Roma Guy (Emily Skeggs) in San Francisco's legendary Castro Camera, basking in the aftermath of Prop 6's defeat in 1977. Director Dee Rees puts a focus on the explosive sound of confetti poppers going off as Roma panics about the possibility of becoming a mother with on-again-off-again girlfriend Diane (Fiona Dourif). Her familiar fear is that being tied down to a family will make her ineffective to her political passions, her need to fight against America's nonsensical, persistent need to persecute those who are not white, male, and, to an extent, privileged.

Those pops of confetti turn into gunshots in the next scene, the ones that would signal the assassination of the legendary Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone in 1978 by Dan White, a right-leaning city supervisor. Celebration and triumph for minorities is always -- always -- followed by severe defeat and extensive loss. It's a mindset that informs, in a way, Roma's inability to see herself as a parent and to imagine herself happy both in her decidedly political career and in her personal life. And that also seems to be the issue with When We Rise on the whole. While attempting to summarize decades of activism, a history of legalized and sanctioned persecution, and the lives of the lesser-known icons of the movement, the series rarely has time to get at the intimate truths and personal moments that defined these people outside of their political importance in the era.

The absence of insight and detail specific to this series is not just a persistent issue in Dustin Lance Black's script (particularly in the first two volumes), but also in the filmmaking. Visually speaking, Gus Van Sant, who directed the first volume of the series (Editor's note: Lance Black directed the final two hours), is one of the most recognizable American directors currently working, and that's as true of his failures (The Sea of Trees) as well as his masterworks (My Own Private Idaho, Paranoid Park, To Die For, Elephant, etc.). Here, you would never know he was behind the camera. And though she has a less developed style, the same goes for Dee Rees, she of Bessie and Pariah, and if longtime TV vet Thomas Schlamme, one of the chief creative forces behind NBC's unparalleled The West Wing, seems to be the series' true visual author, it's only because the look is at once efficient, handsome, and utterly impersonal.

The dialogue in the first two volumes has the tendency to tip toward talking points over personal discussions and distinct opinions, feeling egregiously didactic in certain passages. That becomes a recurring issue, but Lance Black also highlights the warring factions within left-leaning social organizations, a crucial element about how social change is made that rarely comes out in prestige political films or TV series. When Roma arrives back in the states toward the beginning of the series, she wants to work with N.O.W., the legendary women's group, until she learns that the group has a streak of bigotry when it comes to lesbians. This would lead to the Lavender Menace and their uprising during a N.O.W. meeting is one of the more memorable sequences of the series.

The series on the whole, however, is not particularly interested in digging too deep into these complexities, preferring to highlight how compromise and empathy has often brought these groups together to change laws, stigmas, and expectations. As such, When We Rise is exactly what a LGBT rights miniseries on the infamously docile ABC would look like in your imagination: largely simplistic but never dull, interesting but rarely smart, and slathered in music -- some good, mostly bad -- that itself softens the blow of some of Lance Black's best scenes. It's as true of the dollar-store cover of Chic's immortal "Good Times" as the real-deal wastefulness of using Joy Division's unparalleled "Love Will Tear Us Apart," one of the most devastatingly intimate songs ever written, to soundtrack a revolt or rally.

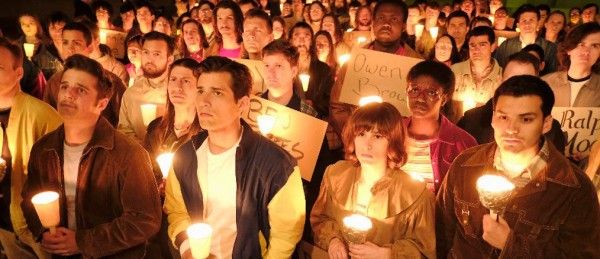

Much like large swaths of the dialogue, the music does a bit too much hand-holding, directing us toward the emotions that Lance Black, Van Sant, and their collaborators want us to feel -- another network TV trope that simply will not die. And yet, it's impossible not to be moved by what these artists have put up here, even if it was by obvious, borderline-condescending design. The series' thrust is how the LGBTQ community went from being an underground, secretive population in cities to a nationwide and, yes, worldwide movement of everyday people, supported by a healthy majority of Americans. In this sense, making a massive, extensively flawed miniseries about the history of the movement and the people who drove it feels like a kind of rite of passage into the mainstream, a long, long time after the people and the movement became fearlessly outspoken critics and antagonists of the mainstream.

The latter chapters boast the better acting and the slightly more involving storylines, as Cleve, now played by Guy Pearce, becomes a central figure in the AIDS crisis, guiding none other than President Clinton around the famous AIDS quilt. We also catch up with Ken (played in his youth by Jonathan Majors and later by Michael K. Williams), a Navy vet who must fight for the right to stay in the home he shares with his longtime companion Richard (Sam Jaeger). Meanwhile, Roma and Diane, now played by Mary-Louise Parker and Rachel Griffiths, must deal with their daughter's curiosity about her anonymous father.

The drama grows more plainly mature in the last few volumes, but the sheer amount of what Lance Black and the creative team are biting off here ends up limiting just how knowledgeable, sincere, and convincing the series comes off as. Clearly, these stories and these people are of severe importance to the makers of When We Rise, but by the end of the series, they remain almost entirely defined by their public personas, even in moments meant to be very private and personal. Even as New York's iconic Act Up! organization begins entering the drama and Ken takes his case up the ladder, there's a routine feeling that these characters are speaking in reminiscent slogans and phrases rather than from the unique experiences of these people. When We Rise deserves quite a lot of credit for bringing these stories to a network that only began to dip its toe into risky waters recently with the introduction of black-ish and Fresh Off the Boat, but in the fight for hearts and minds, there's a clear preference for the former over the latter here.

Rating:★★★ - Worthy Yet Flawed

When We Rise airs nightly, in succession, beginning Monday, February 27th on ABC.