Among graphic novels and limited series, Batman: The Long Halloween has led a charmed life. Its 13 issues, released over 1996 and 1997, are among the most successful and acclaimed comics ever released, their author/artist team among the most celebrated collaborations in the medium. Elements of the story were incorporated into Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight. And it has become the latest comics storyline adapted for the DC Universe Animated Original Movies line, with Batman: The Long Halloween, told in two parts, receiving largely glowing reviews.

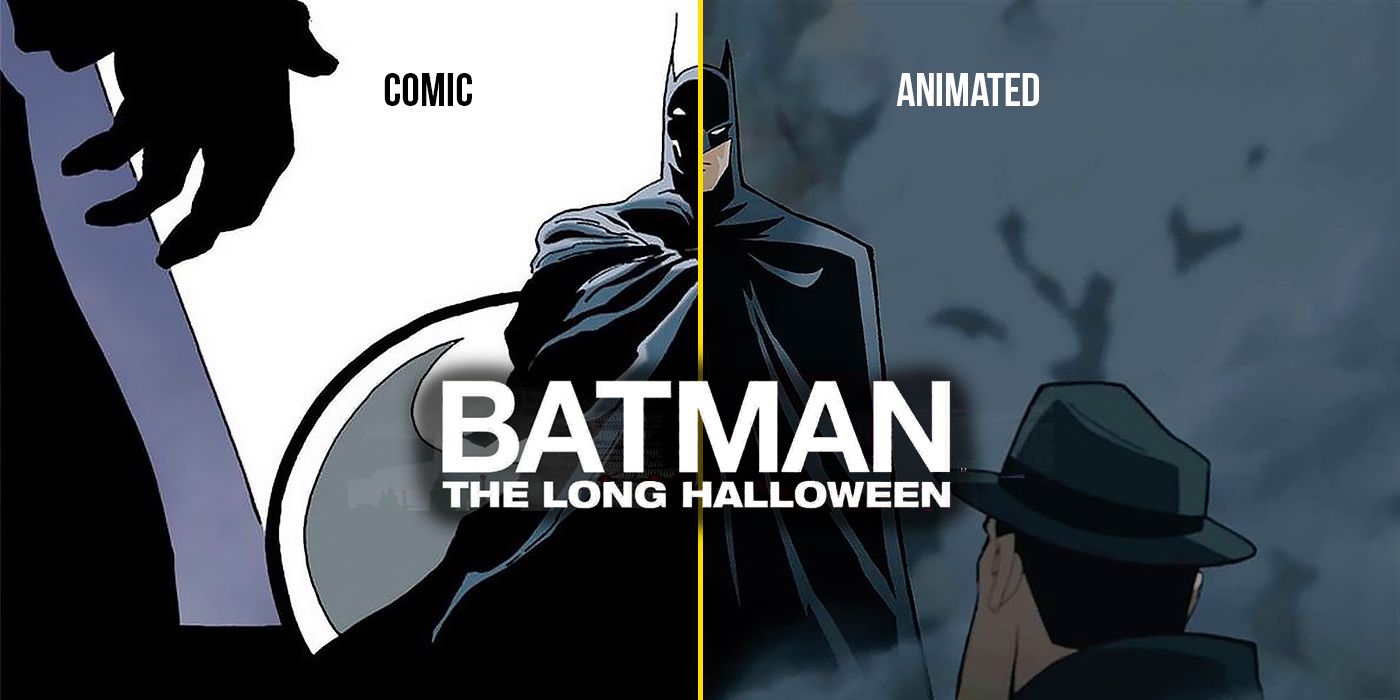

In reviewing those reviews, however, it’s striking how little space is given to discussing the animation of the film adaptation, or its connections to the original comic art. A lack of connection, I should say, because the animated Long Halloween bares little visual resemblance to its source material. This fits a long trend for DC Universe Original Movies. Adaptations of popular graphic novels have made up a sizable chunk of that line’s output, but they’ve seldom tried to replicate the art of these novels. Brian Bolland’s art for The Killing Joke combined realistic human figures and naturalistic shadows with garish, saturated color and grotesque expressions; the 2016 film version used sharp angles to construct its characters and a subdued, desaturated palette. Batman: Year One’s art by David Mazzucchelli also tended toward realism in its human characters, paired with simple coloring in a narrow range of sepia-tinted hues; the 2011 adaptation left that range well behind in its color choices. Hush, originally a yearlong story arc in the monthly Batman comics, saw significant changes in its 2019 adaptation, among them a jettisoning of artist Jim Lee’s detailed line work.

There are reasons for these changes. Comic book art often tends toward intricate detail, whether it’s in musculature, gadgetry, or architecture. Animation, particularly 2D animation, benefits from simplicity; the fewer details that have to be drawn over and over, the easier it is to keep continuity. The DC Universe Original Movies also maintain several timelines, each with its own set art direction. Graphic novels adapted into one of these continuities must be adjusted accordingly. That very consideration influenced the design of The Long Halloween, according to producer Butch Lukic, with DC apparently anticipating more films following on from its timeline.

But it’s worth asking at what point these concessions to economy and long-term strategy harm the adaptation process. Comic books and animation are both visual media where everything must be built from the ground up. Design is a paramount consideration. Graphic novels and limited series like The Long Halloween are also a showcase for the sensibilities of individual artists. One of their selling points is the chance to see such talents at work without the constraints that come with perpetual serialized titles. Surely, in adapting such books to the screen, one of the appealing possibilities is seeing these artists’ work brought to life through movement. No one who worked on the Peanuts cartoons ever thought Charles Schultz’s style needed to be removed for potential future spinoff series.

Nor do such considerations boil down to a matter of taste. I reiterate: comics and animation are designed from scratch. Great artwork in either medium can’t just look good. It should inform and reflect on character, plot, atmosphere, theme, and feeling. It’s style as substance, not style over substance, and animated comic adaptations that disregard the one for even the best of reasons risk damaging the other.

Which brings us back to The Long Halloween, which is one half the origin story of Two-Face, one half a murder mystery around a serial killer who targets mobsters on major holidays. The artist of The Long Halloween is Tim Sale, one of the most individualistic big names in contemporary comics. His is a style not easy to describe except in the broadest of strokes. There’s little concession to realism in Sale’s work. Characters are stylized and distorted to fit their personality, mood, and situation. Sale’s Batman has impractically long ears on his cowl, muscles no real man could obtain, and a cape with a life of its own, growing and shrinking panel to panel with scallops that curl and writhe whenever it’s dramatically effective that they do so. Catwoman goes about in a deep purple costume, the Joker’s smile never leaves his face or has quite the same number of teeth twice (though they are always fully articulated, except when his shadow gets its own smile for one panel), and the scarring on Two-Face’s face is a level of grisly rarely seen away from Freddy Krueger.

Smoke, fog, and weather become as animated as Batman’s cape when necessary in Sale’s artwork. He plays with scale throughout The Long Halloween, rendering the Gotham skyline and the hall of Wayne Manor as impossibly large while shrinking Harvey Dent’s house to a size that is alternatively cozy and claustrophobic. But probably most striking is Sale’s heavy use of solid black. Entire pages will be almost completely shrouded in darkness, with only the barest of essential details showing through. Less aggressive panels still use black to throw long shadows across characters and settings, or to render Batman a looming silhouette lurking over friend and foe alike.

These are the bread and butter of film noir. Filling the frame with black and shadow, expressionistic distortions of scale and atmosphere, and a touch of the Gothic in each character are foundations of the genre. And The Long Halloween is film noir, as a comic book. Sale and writer Jeph Loeb have acknowledged as much several times over the years, including in the introduction to the trade paperback. Beyond the hallmarks of his own style and broad choices in lighting and atmosphere, Sale leans into this element in more overt ways. He dresses the characters (when they aren’t in costume) in fashions from the 1940s. The vehicles, houses, and apartments all fit into that period as well. The mobsters in the story are openly patterned after characters from The Godfather. And Sale’s Gotham has more buildings in the Gothic Revival school than any real city.

Loeb’s writing compliments Sale’s art in creating the noir mood. There is the murder mystery structure of the overall plot, of course, but the finer details support the effect as well. Batman has an internal monologue running throughout, another staple of the genre. The mobsters speak in a manner straight from Mario Puzo, sometimes quoting directly from The Godfather. The dialogue in general follows a certain vernacular, one that doesn’t attempt any naturalism in the way characters talk. It’s stylized dialogue, just as the art is stylized, in the film noir mold.

In the two-part film adaptation, Batman’s narration and the thriller-speak dialogue are gone, as are the overt nods to crime films past. The dialogue tends more toward natural speech, and doesn’t have much remarkable about it other than the fact that the film is more reliant on it than the comic for certain insights into the characters’ minds. The murder mystery structure remains, but significant subplot additions and revisions reduce the focus on that structure to some degree. And Sale’s twisting smoke, giant snowfall, and animated cape are never…well, animated. In place of the black and the Gothic is an art style heavily indebted to comic art from the 1940s. Bold outlines and solid colors surround and fill square-jawed men and curvy women set against an entire city of art deco buildings and roadsters, and not a scene lets the sun come out to play. There’s no great manipulation of scale or of the elements, almost no use of full black for shadow (what shading there is comes from basic coloring and a few digital tricks), and movement outside the action scenes is so limited that it looks like digital cutout animation. The design for Harvey Dent even bares some resemblance to the titular character from Archer. Catwoman is in basic black, the Joker’s shadow never smiles, and Batman himself is a trim, short-eared figure with a well-managed cape.

Tapping into the decade when film noir became a major genre does mean that something of its sensibilities remain in the art of The Long Halloween film, and the murder mystery structure is intact enough for the writing to support that. But that’s only a part of what makes The Long Halloween comic what it is.

Different interpretations of Batman have become legion since 1939. Among the more prominent takes on the character is the concept of him as isolated, obsessive, and perpetually tortured, having never fully grown past the eight-year old Bruce Wayne who witnessed the murder of his parents. This is the Batman that Tim Sale prefers. “[Tim] likes Batman as the solitary figure,” Jeph Loeb agrees. Their collaborations on Batman titles have always leaned into this broken, rather childlike interpretation, and not just in the way Batman himself is presented. Their version of the Scarecrow speaks almost entirely in nursery rhymes, their Mad Hatter almost entirely in verses from the Alice books, and in The Long Halloween, their Joker quotes liberally from Dr. Seuss. Loeb and Sale’s earliest Batman collaborations were a series of Halloween specials for The Legends of the Dark Knight title, and all three feature a brooding Batman facing nightmarish villains who have twisted ties to children’s literature. The last of these, “Ghosts,” is a loose adaptation of A Christmas Carol for Halloween and heavily concerned with Batman’s memories of his own childhood.

These are writing concerns, but many of the elements of Sale’s art that are applicable to film noir – the ominous black shadows, expressionistic scaling on buildings, stylized figures – are also suited to children’s stories. Sale’s designs for such villains as Poison Ivy, The Scarecrow, and the Mad Hatter lean into the fantasy aspect of the characters. His Scarecrow is even taken from an old Disney TV special, The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh. With The Long Halloween, the very notion of a serial killer striking on major holidays is like some twisted children’s book, and Sale takes advantage of each holiday’s iconography and season in their respective chapters for this series. Flashbacks to Bruce Wayne’s childhood emphasize how much he still reveres his parents, and one of the most moving scenes in the comic has Bruce Wayne sit on the impossibly long stairs of the impossibly vast and empty Wayne Manor, tearfully reflecting on a similar incident when he was a boy. All of these elements together give an additional twist to The Long Halloween: it is film noir as fable, a fairy tale as crime thriller.

If the noir element of The Long Halloween is diluted in the film adaptation, almost nothing of these fable qualities survives. A few Alice quotes remain, but the supervillain dialogue is as naturalized as the gangsters’. The underlying premise of a killer staging attacks on holidays, using their imagery in their crimes, is oddly muted despite being integral to the central mystery. It becomes lost in the midst of all those twists and additions to the story, which include an expanded and altered romance between Batman and Catwoman, a backstory and revised personality for Harvey’s wife Glinda, a radically altered father/son dynamic between two of the mobsters, and complications around Holiday’s identity. All heavy plot material - and all rather adult and dramatic, rather than childlike and folkloric. But what most takes away from the fable element of The Long Halloween is the film’s art direction. Characters like Poison Ivy have their fantasy elements reduced, visual quirks like a mobster’s purple eyeglasses are removed, and little effort is made to capitalize on the iconography of any holiday. As for the overall effect: a 1940s throwback is stylized in its own right, but it isn’t the stuff of a broken man-child coping with his pain through Gothic tangles with fantastic crime.

Is any of this necessarily a bad thing? Both parts of The Long Halloween have had glowing reviews. The art deco Gotham City is striking, the character designs solid in still frames (if stiff in motion). Story adjustments give the film some identity beyond an adaptation, reinforced by the changes in art and dialogue. The film is not without its merits.

But it isn’t The Long Halloween.