Earlier today, something happened on Twitter that undoubtedly sent Disney executives into nervous spasms: Song of the South was trending again. It began with Freddy Chambers, a Disneyland cast member, posting his proposed redo of Splash Mountain. In his version, the attraction would now be themed after the studio’s 2009 animated film The Princess and the Frog. (He went as far as to suggest an entire redo of the Critter Country section of the park, with the Hungry Bear restaurant becoming Tiana’s Palace and the very lame Winnie the Pooh attraction becoming a dark ride themed around Princess and the Frog villain Dr. Facilier.) In today’s particularly fraught political climate, with righteous (and overdue) outrage poised at outdated cultural depictions, racially problematic subtext and the glorification of Civil War imagery, there’s a strong argument to be made that Splash Mountain, based on one of the more explosive landmines of Disney’s past, should be gutted and redone.

But maybe it shouldn’t?

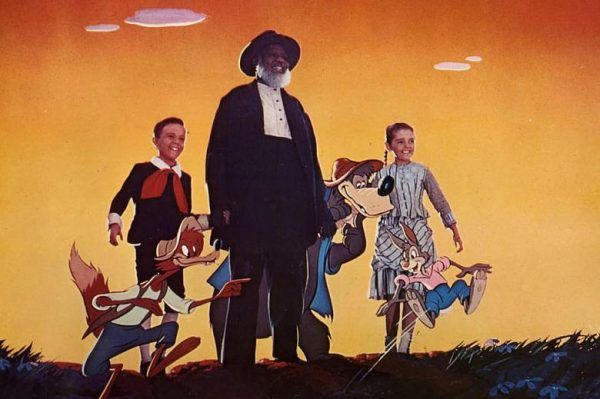

Song of the South, as detailed in the excellent series of You Must Remember This podcast episodes from last year, has always been a lightning rod. Based on a series of stories by Joel Chandler Harris, a white man who adapted (and profited from) stories originated by African and Native American storytellers, that featured a kindly black man named Uncle Remus. Remus would tell fantastical, moralistic tales involving andromorphic animals, most notably Br’er Rabbit, a wily trickster. The property seemed perfect for Walt Disney, whose company had taken a hit during World War II, with an army occupation of the Burbank studio and a lack of worldwide exhibition markets. Walt thought that he could produce the films using a combination of live-action photography and animation, which would allow him to get distributed under his deal with RKO and be much more cost effective. (A fully animated Uncle Remus was considered but rejected.) On his way to the Fantasia premiere in New York, Walt visited the Harris home, “to get an authentic feeling of Uncle Remus country so we can do as faithful job as possible to these stories,” he told Variety (recounted in Neal Gabler’s Walt Disney biography). Roy Disney, Walt’s grumpy, fiscally minded brother, thought the project was too expensive and cumbersome.

Before the screenplay, by Dalton Raymond and Maurice Rapf, was finished, “members of the black community protested that any film version of the Uncle Remus stories was bound to portray black Americans in a servile and negative way” (according to Gabler). One group called Disney’s project “a vicious piece of hocus pocus.” Gabler contends that Walt wasn’t racist but that “like most white Americans of his generation, he was racially insensitive.” Walt’s racial insensitivity (cited by Gabler) included calling the sequence where the dwarfs pile on top of one another in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs a “n***** pile” and some truly abhorrent cultural and racial depictions in movies widely regarded as classics, from Dumbo to Peter Pan to the “Pastorale” sequence in Fantasia. Disney publicists knew they were wading into choppy waters. “The negro situation is a dangerous one,” Disney publicist Vern Caldwell wrote to one of the Song of the South producers before production was even underway.

Raft, a liberal Jew, attempted to soften the screenplay and make it clear that the movie was set during Reconstruction and that Uncle Remus was not a slave, a move that ultimately muddied the waters further and added to the confusing, progressive-but-not vibe. And Walt encouraged input from outside the studio, sending the screenplay to Hattie McDaniel, the Academy Award-winning costar of Gone with the Wind, who offered enthusiastic acclaim and took a part in the movie. Walt also invited Walter White, the secretary for the NAACP, to work with him on script revisions but White refused. Dr. Alaine Locke, a Black scholar and philosopher at Howard University, offered suggestions but suggested the film would “do wonders in transforming public opinion about the Negro.” Still, Locke told Walt that he should have contacted prominent Black leaders before he had commissioned a screenplay.

While Walt tried to quell the concern, outrage was gaining steam. Walt, a paranoid anti-Communist, contacted the FBI to investigate why the Black community was after him and whether the Black-owned newspapers were secretly Communist-controlled. A prominent Black actor, Clarence Muse, spoke out against the project in a Los Angeles newspaper but Walt dismissed it, saying he had turned down Muse for the Uncle Remus role and was just bitter. (James Baskett would ultimately get the role.) While most of the movie was shot in Arizona in 1944—a slow, occasionally clumsy process due to Walt’s inexperience in live-action production—the bulk of the work was spent on the half-hour’s worth of animation. Milt Kahl, a legendary animator and one of Walt’s Nine Old Men, said that Song of the South was “kind of a high in animation.”

And while the film was a modest hit (out performing the box office of Make Mine Music) and warmly received by critics, it rightfully received a huge cultural and political backlash. The NAACP railed against Raft’s confusing change to have Remus happily live on the plantation in a shack. Congressman Clayton Powell called it an “insult to minorities.” Picket lines popped up at theaters. Even Raft agreed that the criticisms were warranted. Walt was mystified. He campaigned for Baskett to get an honorary Oscar and Baskett eventually did receive the award, although he was unable to attend the film’s premiere in Atlanta because the city was still segregated at the time. Baskett died a few months after he received the Oscar.

Even after the controversy, and a public admission (made in 1970, several years after Walt’s death) by Disney that the film had been pulled from rotation, Song of the South survived.

It was released several more times: in 1972, with a slew of new merchandise (including a stuffed Br’er Bear toy, sheet music and records) and a theatrical trailer that this time was more focused around the song “Zip-a-dee-doo-dah” (a song that has its own uncomfortable ties to slavery) but still too-proudly proclaimed “Uncle Remus is back!” The 1972 release was a smash and the film returned the following year on a double bill with, of all things, The Aristocats, as part of a celebration of the company’s 50th anniversary. In 1980, it was released again (“It’s Uncle Remus, telling it like it is, about all those wonderful critters”), timed to the 100th anniversary of Harris’ Uncle Remus stories. The controversy remained but the audience demand seemingly overwhelmed any negative buzz.

In 1984, after hostile takeover attempts by corporate greenmailers, a new regime was installed at the head of Disney, led by Michael Eisner and Frank Wells. Eisner wanted to update the theme parks, particularly Disneyland, which teens and young adults had abandoned for being lame and out-of-touch. (This was a common attitude towards the entire company at the time.)

Conceived by Imagineer Tony Baxter as the Zip-a-dee-doo-dah River Run in the summer of 1983, Splash Mountain killed two birds with one stone: it gave Disney an off-the-shelf flume ride that it could shove in an infrequently visited back corner of the park then known as Bear Country (thanks to its prominent placement of the Country Bear Jamboree) and it could recycle a number of audio-animatronic figures from America Sings, an attraction that, like Song of the South, had adorable animal characters designed by Marc Davis. The model sat in an Imagineering warehouse until a Saturday morning when Wells and Eisner toured the facility with Eisner’s son Breck. The executives were greeted by Imagineering legend Marty Sklar, who toured the building with them. They heard pitches from various Imagineers, including one for an EPCOT pavilion dedicated to movies that would soon morph into its own theme park – Disney-MGM Studios.

“As for Disneyland, no project was more immediately compelling than the elaborate scale model we saw for a flume water ride, climaxing with a steep drop down a waterfall,” Eisner wrote in his autobiography Work in Progress. Eisner dubbed the new attraction Splash Mountain because he liked the subtle tie-in to Disney’s live-action mermaid romance Splash. “Approving an E-ticket thrill ride, we quickly discovered, is an expensive decision equivalent to greenlighting a high-budget movie.” In order to guiltlessly give the go ahead, Eisner decided to re-release Song of the South one last time. If there was no public outcry, and people actually went, then they would proceed with the project.

On November 26, 1986, Song of the South returned to theaters for the film’s 40th anniversary. It was now billed as a “Walt Disney’s happiest classic.” What was noticeable about the promotion for the movie, this time around, was that no live-action elements were presented in marketing materials. Even though the animation made up a third of the movie, it made up 100% of the advertising this time around. (The attraction omitted all human characters as well) As for the surrounding controversy, an Atlanta paper noted that, “The outcry has died down in recent years.” Even a spokesperson for the NAACP, which historically had been one of the film’s largest detractors, said, the organization “has no current position on the movie.” The re-release was a smash and made almost as much money as it had in 1946.

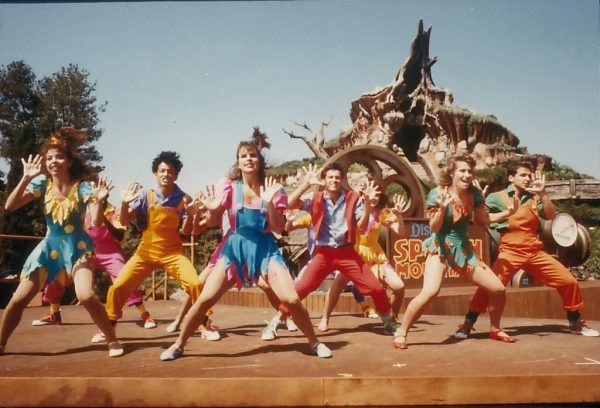

The attraction, which Eisner later called “perhaps the most ambitious project we undertook at Disneyland,” broke ground in 1987. Initially planned to open in October 1988, with large promotional partnerships with Coca-Cola and McDonalds, the attraction was ultimately pushed back, first to the beginning of 1989 and then to July 17, 1989. (Disneyland opened on July 17, 1955.) Building the attraction wasn’t as easy as they had initially hoped; the incline was too steep and the ride vehicles initially took on too much water. A Los Angeles Times report said that, with all the overruns, “it will wind up costing an estimated $70 million--instead of $20 million to $25 million--making it by far the most expensive ride ever built.” (There was nothing about the problematic nature of the attraction’s source material.) A prime time special promoting the attraction, hosted by Jim Varney’s Ernest character, including a particularly cringe-worthy element that suggested nobody at the company was worried about the attraction’s icky past: a Splash Mountain rap. “Crowds loved Splash Mountain,” Angela Bassett delicately narrates on The Imagineering Story. Critics, on the other hand, were more mixed. The Los Angeles Times frowned: “We look to Disney for great stories, and with Splash Mountain you have to work to find one. These days, the park’s George Lucas-affiliated attractions serve the imagination better than those created by Disney’s own Imagineering staff.” The review doesn’t mention Song of the South or express any moral objections to opening the attraction. In 1992 the attraction would open in Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland.

In the years since Splash Mountain opened, the company has gotten better and better about erasing its connections to Song of the South. It has never appeared as an official home video release in the United States, although there was a heavily bootlegged Japanese laserdisc released at some point. And it rarely issues new merchandise, especially if it’s unconnected to the attraction. Earlier this year, former Disney CEO Bob Iger said that Song of the South would “never” be released on home video, including on the company’s new direct-to-consumer platform Disney+. At a shareholders meeting, he said the film was “not appropriate in today’s world,” although it wasn’t okay in 1946’s world either.

And that’s chiefly why Splash Mountain should stand tall, with its problematic theming intact – it’s a giant, towering monument to a regrettable part of the company’s past that makes it impossible for Disney to totally get away from Song of the South. It’s the reason why CEOs still get pestered at board meetings and why new podcasts are produced about the movie that inspired it. Because every time somebody rides the attraction, they’re going to ask where the animals came and catchy songs came from, and they’re going to discover the painful truth. Splash Mountain as it is today holds the company accountable and encourages discussion and dialogue from those that ride it and between the company and its customers. As an attraction, it’s an utter masterpiece of design and engineering, full of Baxter’s rich details and a narrative playfulness missing from similar flume rides. That can never be taken away from it. But its origins are dangerous and demand investigation. It’s much easier to keep a DVD off the market than it is to raze or dramatically re-theme an entire building. Disney hates any and all conversation around Song of the South, but with the construction of Splash Mountain it made that conversation inescapable.

And please note that this is not an argument for keeping Confederate statues up or letting the same flag fly at NASCAR games. Song of the South is a movie whose message and stereotypes are definitely enough to make you queasy. But it doesn’t explicitly endorse the Confederacy, slavery or the subjugation of anytime. (If anything, its cheeriness is naïve and insulting in a different way.) As much as Walt Disney was a futurist, he was also someone deeply connected to nostalgia, able to tap into a version of the past that never really was. And a warm-and-fuzzy version of the post-Civil War south is definitely something imagined and not actually experienced. Leaving Splash Mountain alone is important because, without lionizing a racist general, some of those same debates could be had, especially with the company that made the bad decisions in the first place.

Which brings us to the potential Princess and the Frog re-theme. Firstly, we should not forget that the film had its own bumpy history: at an early investors meeting, the film, then called The Frog Princess, featured a lead character named Maddy, who served as a chambermaid to the spoiled Charlotte. After a very public backlash, the filmmakers (two white men: Ron Clements and John Musker) backpedaled; her name would be Tiana and she would be friends with the spoiled white girl. Hostility would be smoothed away, in the process leaving the character somewhat drab. (Also, you’re going to give the world Disney’s first African American princess but only let her be a human being for, what, ten minutes?) Ultimately, the film was a modest hit that has gained appreciation in the years since, and its strides towards diversity and inclusivity cannot be overstated.

But it doesn’t need to take over Splash Mountain, in the same way that the Guardians of the Galaxy slid into the Twilight Zone and turned Tower of Terror into Mission: Breakout at Disney California Adventure. For one, Disney shouldn’t feel the need to swap out a problematic black story for a more positive black story. That, in a way, feels trite and pandering, a swing in the other direction that feels far too calculated and cynical.

And here’s the other thing – Princess and the Frog deserves its own ride. There should be a dark ride, the slow-moving, carnivalesque attractions that either reproduce or further explore an animated classic that you already know and love –think Peter Pan’s Flight or Ariel’s Undersea Adventure. There should be an attraction like that for Princess and the Frog, an attraction where young black kids can look and, for the first time, see themselves in the cutting-edge audio-animatronic figures staring back at them. The story of Princess and the Frog shouldn’t have to move into Splash Mountain; it deserves its own elaborate show building, with brand-new figures and a story worthy of its voyage through the bayou. Maybe a boat ride in the style of Pirates of the Caribbean? (If the attraction is located anywhere besides New Orleans Square, god help us all) Whatever it is, the Imagineers are undoubtedly willing to take on the challenge.

But leave Splash Mountain where it is. And let Disney spend however long it stands answering for it.