Edgar Wright is one of the most signature reinventors of genre working today. Wright’s films openly acknowledge and frequently reference their classical inspirations, but they’re not outright parodies that fail to develop an identity of their own. Shaun of the Dead is obviously indebted to the work of George Romero, but it stands alone as a compelling story of a friendship that’s no longer productive. Hot Fuzz is a critique of restrictive communities unwelcoming to outsiders that also happens to be filled with callbacks to classic buddy cop films (most notably Point Break and Bad Boys II). Although it's likely his most sincere work, Baby Driver successfully merges the innocence of classic Hollywood romances within an epic car chase saga of the Bullitt and The French Connection era.

Compared to these definitive subversions of established stories, the influences on The World’s End are harder to immediately identify. While the story is revealed to be one of a latent alien infiltration of a small town akin to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the concept of old friends reflecting on their youthful ignorance is closer in line with ensemble dramedies like The Big Chill or American Graffiti. It's a unique blend of inspirations that Wright connects thematically; the characters reflect that their once seemingly welcoming home now feels different, even “alien,” in their older years.

The zippy pace and constant barrage of quips are so immediately entertaining that the drama at the heart of The World’s End may not immediately register like Wright’s other films; the death of Shaun’s mother is immediately tear jerking in Shaun of the Dead. Yet, the study of addiction and use of nostalgia as a crutch to bury adult responsibilities is the most mature throughline he’s ever developed. Without sacrificing the gleeful comic energy that launched Wright’s career, The World’s End is a devastating depiction of clinging to an idealized past.

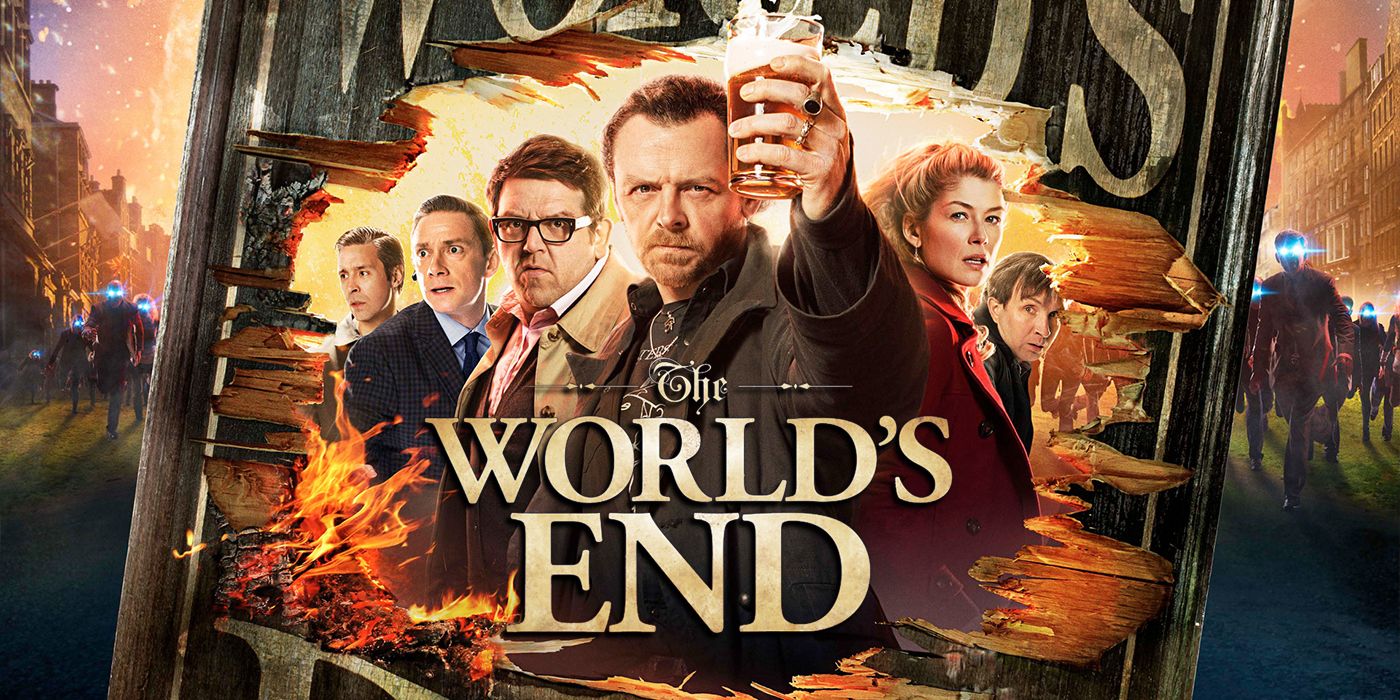

Simon Pegg’s Gary King establishes the stakes within the film’s opening moments. A humorous story about his high school drinking adventures with friends Andy Knightley (Nick Frost), Steven Prince (Paddy Considine), Oliver Chamberlain (Martin Freeman), and Peter Page (Eddie Marsden) closes by revealing where the framing device actually takes place. King is in therapy, recounting the beginning of his alcoholism like it's a hilarious anecdote shared between drinking buddies. “As I sat up there, blood on my knuckles, beer down my shirt, sick on my shoes, knowing in my heart life would never feel this good again,” King gleefully recounts. “And you know what? It never did!”

In his greatest performance to date, Pegg is simultaneously hilarious and tragic. He revisits his old gang together to supposedly relive their glory days, but the guys he used to think would always be there for another wild misadventure have all moved on with their lives. Knightley has quit drinking altogether, Steven has long forgotten his quarrels with King over their shared crush Sam (Rosamund Pike), Oliver is a fast talking real estate agent, and Peter is a manager at a car management company.

King wants to relive the legendary “Golden Mile” challenge that they failed to complete as teenagers, deceiving each of his friends as he masks his issues. Falsifying his mother’s death to the sober Peter, who was involved in a drunk-driving accident with him, is a particular low. As they venture back to Newton Haven, King is the only one who doesn’t notice how drastically different it is. He’s joyful remembering events from high school, while the other characters are immediately struck by how cold and uninviting the town’s residents are during their first few pub visits.

Wright chooses the perfect time to reveal the sci-fi twist. King has sparred with Peter after he ignores Peter’s heartfelt recollection of a childhood bully, and drunkenly stumbles into a bathroom. King’s friends are denied the chance to admonish him for his lies when the android replicants haunting their town reveal themselves, leading to a visceral brawl where their goopy blue insides are revealed. King’s plan to stick with their crawl forces each of the characters to do the same thing he’s been doing his entire life - pretending they’re still in high school and nothing has changed.

King’s willful ignorance is evident as he fails to acknowledge the consequences his friends face as they continue in their quest. Oliver and Peter are assimilated into robotic doppelgangers and Steven is captured, leaving him alone with Andy for the first time since their accident. The pressures of the night have caught up to him, and he’s begun drinking again. However, seeing King continue in his hopeless pursuit to reach the final pub, The World’s End, is enough to force the confrontation they never properly had.

Their resulting argument is the most brutally honest that Wright has ever conceived. It doesn’t exonerate King for his willfully malicious behavior, but details the severity of his torment when he breaks down to Andy and his suicide attempt is revealed. King cries that completing the “Golden Mile” is the only thing he can achieve, and he’s placed in an even more vulnerable position when he becomes humanity’s last standing representation to the android system “The Network.”

What’s most impactful about this clash of tones is that Wright’s dialogue is as sharp as ever (“What the fuck does WTF mean?” being a particular favorite), and Pegg retains his rapid fire delivery. It's also definitively weird, and the fact that The World’s End ends with mankind returning to the Dark Ages and still remains hopeful is a credit to how unique Wright’s perspective is.

King is ultimately a survivor. His path of healing has only just begun, but amidst the post apocalyptic final scene he’s followed in Andy’s perspective and given up drinking. He reclaims his childhood nickname “The King,” and it's unclear if this is an empowering moment of closure or an early warning that his recovery will be a challenge. Ambiguous, heartbreaking, and uproarious, it's the perfect ending to the most powerful and personal film of Wright’s entire filmography.