Werner Herzog is an infamous madman. When he isn’t eating his shoe on a bet or insisting on finishing an interview despite having been shot with an air-rifle, the German director makes astonishing films that blur the line between fiction and documentary, like noted philosophical jungle epics Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo. In the midst of such epics, he once made a little-seen but mesmerizing drama with a twist as odd and original as the man himself. Heart of Glass remains notorious as the film for which Herzog hypnotized his entire cast, resulting in bizarre and trancelike performances. The film is all too often overlooked beyond this famous anecdote, which is simply a shame. It’s an altogether powerful and bewildering cinematic poem, with the hypnosis not a mere gimmick, but an important element of the film growing organically from its themes.

The film is set in a remote, 18th-century Bavarian village largely supported by a glassblowing factory. After the lead glassblower dies, the entire town hopelessly scrambles to find the secret of his popular ruby glass, implied to have been their primary export. Eventually, they descend into a collective insanity. If this makes the film sound like a thrilling journey into madness, in actuality it has a far more contemplative tone. Very often does Herzog’s documentarian lens just sit back and watch the behavior of these people, in static master shots that run long. One can see that these are people who, in their inability to continue producing the ruby glass, have lost their sense of purpose. This is where the hypnosis comes into play.

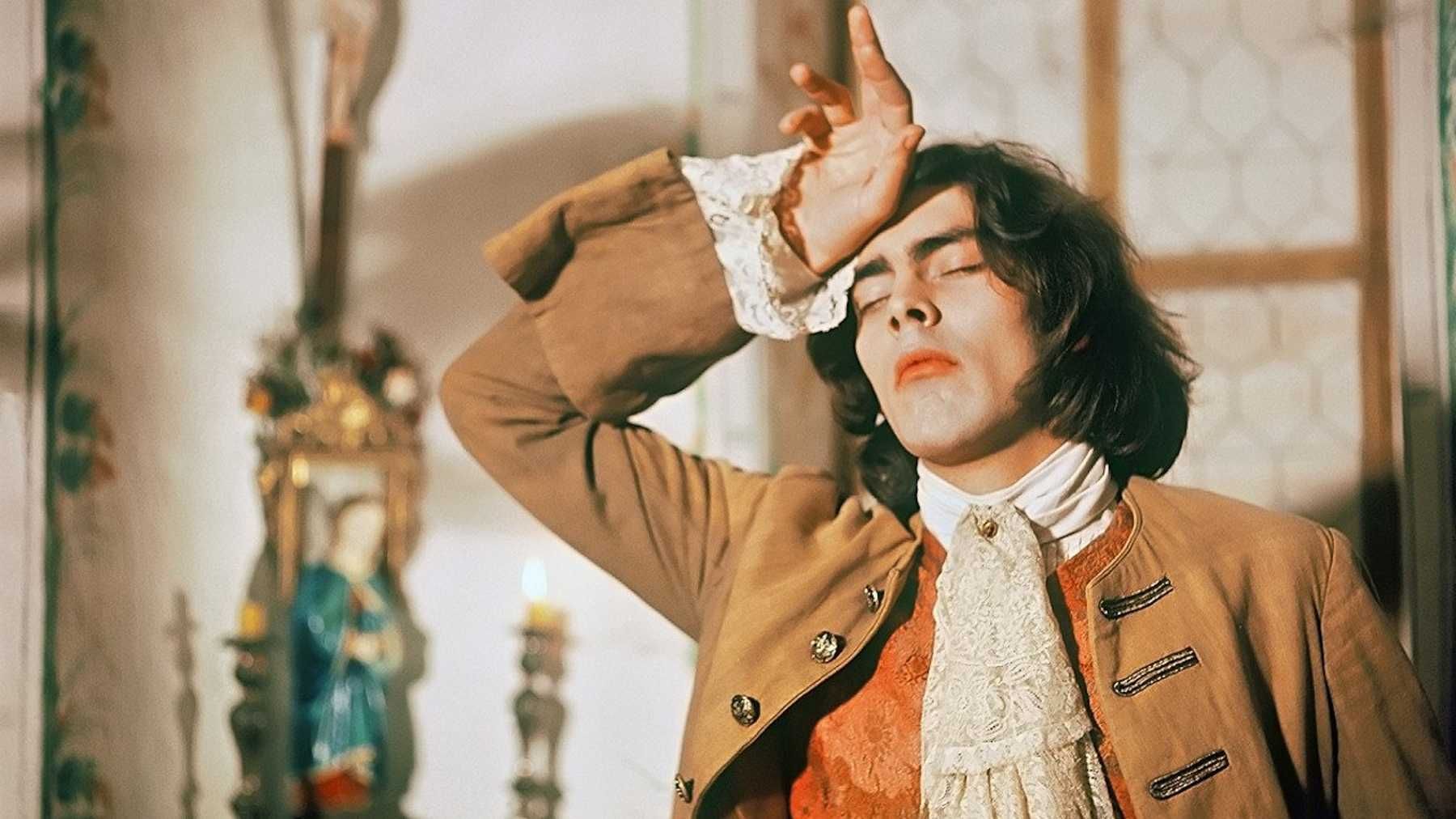

Herzog hypnotized the actors himself, claiming to have fired the professional hypnotist for peddling “new age bullshit.” The director would get the actors in an entranced state before drilling the dialogue into their memory. Each scene would then be shot very quickly in one to two takes. Beyond feeding them their dialogue, he kept the direction very loose, allowing their unconscious condition to bring upon many odd, improvisatory gestures and movements. A scene early on illustrates just what this looks like. In the town’s central bar, two men sit across from each other at a table. Their bodies are stiff, and their stares blank. They speak without any intonation, and as they sip beer, their eyes roll back into their heads. Despite a lack of any passion or emphasis, their dialogue indicates an argument. Eventually, one mechanically breaks a beer mug over the head of the other, who is so far gone that he doesn’t even flinch. The entire town goes about in this dazed manner, stumbling and grumbling quietly while always staring forth at nothing in particular.

The film evades succinct explanation for this peculiarity, and yet, it can be easy to read into when familiar with the director’s obsessions. Herzog is often very critical in his work of people who are driven by greed. Those who value finances over more self-sufficient, humanistic endeavors tend to be presented with absurdity. The capital export of the ruby glass, then, becomes a perfectly futile replacement for a meaningful existence in the village. Without it, the townspeople become zombies awoken from their financially secure, but otherwise empty, slumber. The glass has functioned as something of a shield from cold reality, which the sleepers now have to drowsily face. In seeming support of this perspective, the heir to the factory (Stefan Güttler) once asks, while rambling madly about the loss of the glass secret: “Now what will protect me from the evil of the universe?”

An apocalyptic current also runs through the film. Its lead character is the disquieting prophet Hias (Josef Bierbichler), who meditates in the misty mountains above the town and sees only dreadful and nightmarish things in the future both near and far. It is claimed that Bierbichler was the only actor left lucid by the director. Although his performance appears just as spaced out as anyone else’s, Herzog clarifies that his is a “penetrating” glare. While the general townsfolk aren’t focused on anything, Hias is always focused on his distant visions. This importantly separates him from the other characters and helps to provide another explanation for the significance of their hypnosis.

Early on, the mystical abilities of Hias are proven when he correctly predicts the inexplicable death of one of the bar patrons. Even so, when his visions begin to involve impending cataclysmic tragedy for the entire village, none of the villagers listen to him. In a pivotal scene, he spews relevant apocalyptic forecasts in the crowded bar, but all the surrounding patrons are more concerned with drunkenly getting a young woman to strip. Despite having access to their dark fates through Hias, they go on like automatons with their trivialities. Sitting on a ledge over the town later, Hias ruminates: “Like sleepwalkers, they march towards their doom.” Hias is typically shown in outdoor settings of the sort looking far off into the physical distance. In contrast, the townspeople are usually seen indoors, looking only toward those things right in front of them. These associations serve to further visualize Hias’ foresight and the townspeople’s lack thereof in purely cinematic terms.

It’s only fitting, in a film with so many entranced actors, that the filmmaking itself would be designed to put the viewer into a hypnotic state as well. An extended prologue and interlude place the ambient rock jams of Popol Vuh over beautiful shots of nature, from extreme close-ups of rushing water to a very early instance of time-lapse photography portraying moving clouds. Even putting these mesmerizing moments aside, the observational style allows for scenes to play out in their mundane reality, or even their unfiltered surreality, which can become equally entrancing. On one end of the spectrum, the film follows in the tradition of neorealism, with un-stylized documentary scenes of actual glassblowers at work embedded in the middle of the drama. On the other end, the film can often enter the realm of pure otherworldly surrealism, with scenes ranging from a man slow dancing with a fresh corpse to a young woman shrieking at a harpist as he plays in the dark.

If this mix of sensibilities is any indication, the film is radically experimental in ways far beyond its approach to actors. It’s a work as challenging as it is poetically moving, just as the best Herzog films are. Whether the actors were hypnotized to portray their characters’ crippling greed, or their blind walk into disaster, perhaps the resultantly odd performances are best seen as one major milestone in Herzog’s tireless efforts to show the viewer something new, strange, and ultimately beautiful in its truth.