For as long as I can remember, people have been telling me I was born in the wrong time. All the clothes I like to wear are decades to centuries out of fashion. A good percentage of the music I listen to requires an orchestra. My favorite sort of weather is snowy, and unless COP26 represents a turnaround in climate negotiations, that’s increasingly going to be a thing of the past. And while I’m not nearly as versed in classic cinema as some of my friends and family think I am, I do like to watch old movies. In the case of horror films, my tastes are almost exclusively old.

I’ve been a fan of classic horror for many years, but in all that time, the films have technically failed in their intended task: scaring me. They’re entertaining, certainly, and the best of them can engage with a viewer beyond that level. The Wolf Man (1941) is a genuinely moving tragedy. The Bride of Frankenstein is at once an earnest plea from society’s outcasts and a burlesque of the original Frankenstein (1931). Themes of romance and spirituality are the strongest selling points of The Mummy (1932). And Godzilla (1954) is probably the most haunting nuclear allegory in film (this coming from someone whose opinion of allegory usually aligns with J.R.R. Tolkien’s.) That’s not to dismiss the entertainment factor, of course; mad scientists, shapeshifters, ghosts benevolent and malign, and gill-men of the Amazon are all just plain cool. These movies inspire laughs, tears, excitement, and aesthetic pleasure, but even when I was ten, none could inspire chills.

None, that is, except for the vampires.

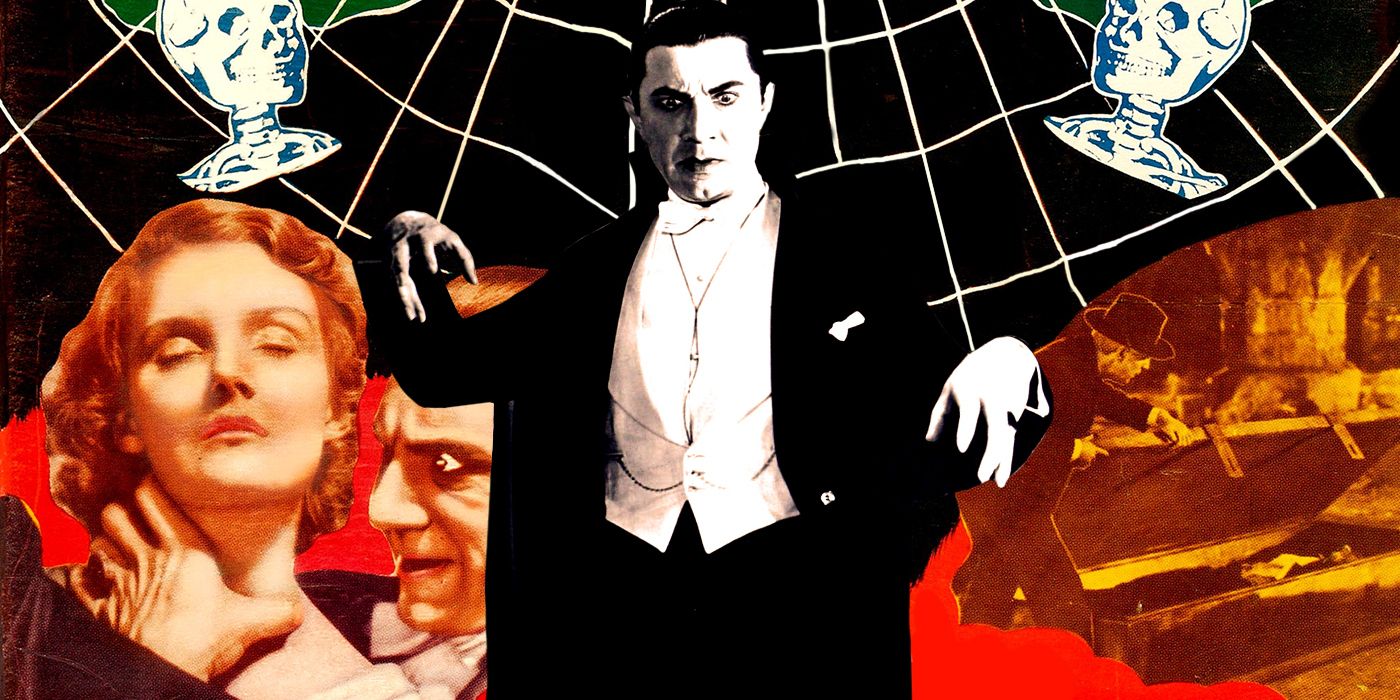

I first saw a serious vampire movie through AMC’s Monsterfest in 2000, when they played Dracula: Prince of Darkness. Host Whoopi Goldberg warned that Christopher Lee, even without dialogue, could still “scare the you-know-what out of ya” as Count Dracula, and when his manservant bled a freshly-murdered corpse over his coffin to fulfil a resurrection ritual, I decided she was a little too right. I quit the film midway through and bowed out of watching anything else on “vampire night;” too much blood for my fairly sheltered 10-year-old self. Besides, a much safer option was available at the local Blockbuster: the 1931 Dracula, directed by Tod Browning and starring Bela Lugosi. It was in black and white, so there was no red gore to worry about. And I knew enough about movie monsters by then to know that Lugosi’s was the face and voice of Count Dracula in pop culture. Cartoons, commercials, stand-up comedy bits, Sesame Street – they all used Lugosi. That didn’t tell me anything about what I was in for with film itself, and I wasn’t looking for a soft, cuddly experience in basic arithmetic, but I was looking for a vampire movie that wouldn’t creep me out so much that I couldn’t finish it.

The hope was half-met. I made it to the end of the film. I couldn’t have abandoned ship if I wanted to. There weren’t any big shocks or flashes of violence to trigger the instinct to shut the thing off, but it was more than that. From the performance of its lead to the decadence of its direction, Dracula wasn’t like anything I’d seen in the movies before. It’s not like most films I’ve seen afterwards, even in its genre, even from its time. And it creeped me out like no work of fiction has before or since.

Things started out ordinarily enough: opening credits set to music, in this case an excerpt from Swan Lake. To this day, I think of that excerpt as Dracula’s theme more than a piece of Tchaikovsky’s ballet. But Swan Lake stood out all the more for being the only piece of non-diegetic music in the film. Dracula was produced shortly after the transition from silent film to sound, and in that transition, the musical accompaniment standard to silent film was lost for a few years. Besides Dracula, Frankenstein, The Public Enemy, Scarface, Little Caesar, and many more films of the early 1930s had no music except when it was present within a scene. But I had never watched a movie without a score when I first saw Dracula, and it still strikes me as unique in its lack of sound. Other films of the time had copious amounts of dialogue, sound effects, and extensive diegetic music. In Dracula, there are long stretches of nothing. The only sound was the cackle of the decayed audio track (since removed in the restoration of later home video releases). That soft, low cackle, stretching on for minutes, was the first thing that got under my skin.

Not helping were the images that went with the cackle. Nearly every cliché in traditional horror design comes from the 1931 Dracula. The crumbling castles, the cobwebs, the rough textures and pervasive darkness; they’re still the go-to for anyone looking to easily get across a spooky vibe. But so much has been lost in translation through the years. Between built sets and hand-painted mattes, Hollywood’s studio system could sell scale as well as any modern movie, with the added benefit of being made of tangible materials. The ruins of Dracula’s castle looked massive, even on a small, made-in-the-90s TV screen. The lighting was careful to emphasize texture without compromising the darkness of the image, making details like the tiny patches of fog billowing out of the earth or the smear of slime on a staircase stand out. There are plenty of shows and films with cobweb-coated settings, but few have the enormous spiderweb that consumee the grand staircase of the castle. And when the camera isn’t lingering over all this oversized ruin as if it were desired ornamentation, it lingers on vermin. Giant bugs crawling out of coffins. Bats, rats (or at least, opossums playing rats to appease the censor) and armadillos somehow transported to Romania. And mixed in with all these reveals, as if they were part of the infestation, the vampires: three hollow-eyed, cadaverous brides and Count Dracula himself.

Bela Lugosi has become one of my favorite actors. I’ve seen him playing other vampires, or people pretending to be vampires. I’ve seen him as old Ygor in the Frankenstein series. I’ve seen his few heroic roles, some staged interviews, and more of the poverty row quickies he was forced to peddle than I care to admit. He never gave a performance quite like what he gave in Dracula. It’s such a bizarre, unnatural portrayal, and yet he’s absolutely convincing. None of the imitations and parodies in pop culture come close to matching it. Lugosi never blinks in the part. The intensity of his focus when speaking to other characters is palpable. His body language is so firm, it’s no wonder Disney would think of him as a model for their devil in Fantasia. The phrasing and intonation in his voice goes beyond the natural quirks of the Hungarian accent to stress Dracula’s alienation from the rest of the cast. And the filmmaking knew exactly when to emphasize Lugosi’s choices: the camera tracks in on his piercing stare when he first comes out from his coffin, and pinpoint lights illuminate his eyes throughout the film. More than anything else about Dracula, Lugosi was the reason I couldn’t stop watching. He was just so weird as he coaxed a clearly unnerved Renfield into his castle, plied him with drugged wine, repelled his three brides as they advanced on the unconscious realtor, bent over the man himself, and…

And that was it. It wasn’t hard to guess what Dracula did, but nothing was shown, and that restraint was where I really started to get scared. The other black and white horror movies I’d seen were hardly violent, but when the Wolf Man attacked someone, you saw him bite at their throat, even if it was in a wide shot that obscured the action. Frankenstein’s monster and the Gillman would grab people by the face or the throat to kill them. Boris Karloff’s Imhotep used his magic to bring death to his foes, and crosscutting showed the effect of his spells. But this business of fading to black before anything concrete happened was a new experience, and being the sort of kid who worried to death over the unknowns of real life, my mind was so much more unnerved by this unseen act of vampirism than I had been by the bloody resurrection of Christopher Lee. The fact that Dwight Frye’s Renfield became so unhinged after the attack that I couldn’t immediately recognize him as the same actor and character, didn’t help.

The unseen – the unknown – persisted even as the indulgently ruinous castle was left behind. Dracula assumed the forms of bat, wolf, and mist, but any transformation was achieved through cutaways. Dracula invaded the rooms of Frances Dade’s Lucy and Helen Chandler’s Mina to attack, but the camera never showed his lips touching them, only the aftermath: death and vampirism for Lucy, a gradual descent toward that end for Mina. The long stretches of silence continued, Lugosi kept up the weirdness, and Frye’s Renfield was just as bizarre with his demented chuckle and manic swings in personality. But there was one more unsettling performance to come: Edward Van Sloan as Professor Van Helsing. While he isn’t a close physical match to the description in Bram Stoker’s novel, Van Sloan’s Van Helsing is among the closest film portrayals to matching the intent of the character. He’s aged, wise, and undeniably on the side of the angels as he safeguards the rest of the cast from Dracula’s power. Van Sloan’s Van Helsing tends to patronize Renfield, Mina and her fiancé John Harker (played by David Manners), speaking to them as if they were children. But he never treats Dracula that way. As I watched the film, I got the sense that in all his confrontations with the count, Van Helsing was enjoying himself. He was so sly in the way he used a mirror to expose the presence of a vampire, so smug when he succeeded. Their verbal sparring later in the film seemed more like banter in a game than a battle for the life of a young woman. A grin curled at the edge of the professor's mouth whenever he made a riposte, and the grin came with bulging, delighted eyes when he vowed to strive a stake through Dracula’s heart. Alone among the cast, Van Helsing resisted Dracula’s hypnotic power (with great effort), and he got in one more self-satisfied flourish in the way he pulled a crucifix on Dracula like a gunslinger. “He might be the hero,” I thought, “but this guy’s just as scary as Dracula!”

I made it to the end of the movie, where Van Helsing stakes Dracula and Harker and Mina flee from the ruins of Carfax Abbey. I wasn’t bone-white or shaking with dread when it was all over. But I did have a bed in those days that was right up against the window. When the lights were out and my brothers were asleep, I kept eyeballing that window, which suddenly looked a lot like the one in Lucy’s bedroom in the film. Sleep did not come easy that night, nor the whole week after.

Dracula left me with some very firm attitudes and prejudices about horror films. It helped push me toward preferring fantasy-horror over sci-fi-horror. When no vampire came through the window for my blood, I realized that being truly scared by a movie could be fun, though to date, only the original Nightmare on Elm Street and The Exorcist have come close to matching that childhood experience with Dracula. And I’ve decided ever after that vampires must be villains. There are no shortages of monsters that are sympathetic, misunderstood, tragic victims, and metaphors for human foibles and plights. When treated with that degree of intellectualism, vampires as defined by Lugosi’s commanding and unsympathetic portrayal seem ideally suited to represent the sociopaths, fascists, predators, and robber barons of society: undeniably human beings who have forsaken their humanity. In less thoughtful works, I still like to see them as the baddies, even comical or incompetent ones. This is, of course, well out of step with the current fashions in horror fiction, and it’s left me hostile to such acclaimed works as The Vampire Chronicles and Hotel Transylvania (Genndy Tarkovsky’s one great sin in an otherwise faultless animation career). But such is the influence of Browning and Lugosi that I permit no exceptions – well, maybe just one.

I’ve watched Dracula every Halloween when possible, and on many occasions outside the season. I’ve learned a great many things about the film, things that I would never have believed if you told me when I was ten. I certainly wouldn’t have accepted the idea that Dracula – the one and only classic horror film that kept me up at night – was a “creaky antique that seldom budges the needle on the drama meter…only Lugosi freaks and the nostalgically inclined still go through the motions of praising and defending the film.” Yet that’s how film historians Tom Weaver and John Brunas describe it in their book Universal Horrors, and among aficionados of these movies, it’s almost a consensus opinion that Dracula is more important than good. Its source material was the Hamilton Deane/John L. Balderston drawing room play as much as Stoker’s original novel, leaving the film vulnerable to charges of being “stagey.” Except for Lugosi and sometimes Frye, the acting is dismissed as dull to laughable. An anecdotal account by David Manners that Tod Browning was a nonentity on set, the only direction coming from cinematographer Karl Freund, was taken as gospel by critics and historians. And when Universal unearthed the Spanish-language Drácula, shot simultaneously with Browning’s film by a separate cast and crew, it was quickly held up as a superior effort. The DVD documentary The Road to Dracula takes pains to stress the Spanish version’s “technical” superiority: it makes greater use of the moving camera, it claims, avoiding the creaky stage-bound feeling of Browning’s film, and it emphasizes the sexual undercurrents of the story through the decolletage of the heroines.

Even when I was a teenager, I thought that last argument sounded more an expression of adolescent lust than a serious assessment of cinematic quality. The appeal to technology has never moved me either; Michael Bay employs more technical wizardry in many of his films than Christopher Nolan did in Dunkirk, but who’s going to try and claim Bay’s the better filmmaker on that logic? As it happens, film historian Gary Don Rhodes is enthusiastic and pedantic enough about Dracula that he counted the number of moving camera shots in both versions, and there are more in Browning’s film. Not that quantity matters over quality; I suspect that Drácula gives the impression to new viewers of doing a lot with the camera because of the showiness of some of its crane shots, but the effect is more Busby Berkeley than Bram Stoker. Rhodes did his research for his book Tod Browning’s Dracula, where he also pushes back on the idea that Browning was an absentee filmmaker and that the film was too reliant on the stage play. The final script for the film is a hodgepodge of Stoker, Deane/Balderston, and original contributions from several writers, including Browning himself. Browning continued to make alterations during filming (where the changes were made can be easily spotted by referring to the Spanish version, which followed the script). The result was significant improvements to such pivotal scenes as Dracula’s attack on Renfield and his confrontations with Van Helsing. And given how different Lugosi’s performance in Dracula is to anything else he did on film, it’s hard to imagine the director had no say in shaping the title role.

I’ll concede to some of the critiques of Dracula. Browning’s cuts included the resolution of Lucy’s fate as a vampire, a key element of the novel. David Manners, whose career in Universal horror was exclusively made up of thankless male juvenile roles, was handed his most thankless in Jonathan Harker. Mina, such an intelligent and active character in Stoker’s novel, is made a standard-issue damsel in distress for the film. But I still love it, warts and all. It remains my favorite horror film. And every now and again, if it’s the right sort of weather on Halloween night and I shut all the lights out when watching Lugosi’s masterclass performance for the millionth time, I can still be slightly uneasy getting into a bed too close to the window.