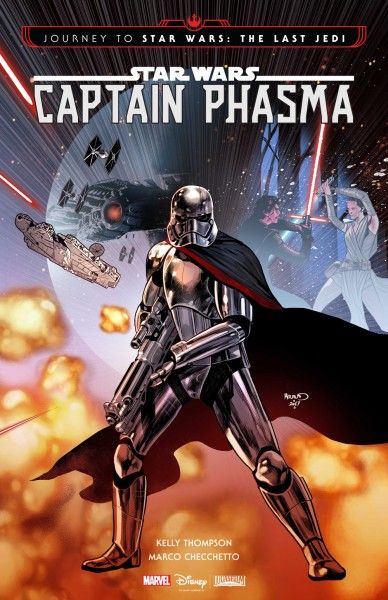

The reason that studios value intellectual property (IP) so much is that it can be spun out in so many ways. Something like Star Wars always keeps the merch train rolling because you’re not really selling Star Wars: The Last Jedi. You’re selling all the tie-in books and all the comics and all the other ancillary revenue streams. Some of this stuff doesn’t require a story like a t-shirt or toy, but some of it does. We’ve now reached the point where the story is indistinguishable from a product, and on the surface, it seems like a perfectly natural exchange for goods and services. I want to know more about Captain Phasma, there’s a comic book called Star Wars: Journey to Star Wars: The Last Jedi – Captain Phasma, I will pay $12 to know more. However, this investment goes beyond the monetary. It’s time and attention, and then frustration begins to creep in because the “big” story, the main IP, fails to properly recognize its offspring, the comic you just purchased.

I noticed this trend online when looking at some reactions to Star Wars: The Last Jedi, but it’s a sentiment that could be applied to any major IP that creates ancillary stories. There’s a concept of the grand, unified story where every piece of ancillary writing has been thoughtfully tied into the whole, and each piece considers the other. Presumably, there’s a story group that oversees everything, and makes sure that the tie-in novel is accurately reflected in the motion picture, and vice-versa. Never mind that different mediums have different schedules, creative inputs, and processes. The quality assurance test here isn’t for actual quality; it’s for consistency. As long as it’s consistent, it is good.

Unfortunately, this approach not only neglects how stories are put together, and the timetables everyone has to work on when trying to craft their own story; it also holds storytellers to the wrong standard. Instead of each storyteller trying to tell the best story possible within their given parameters, the new standard is, “Does it adequately agree with an ancillary revenue stream?” So, to continue with our Last Jedi example, Rian Johnson’s goal is no longer to tell the best story possible, but to make sure that he’s made adequate recognition of Star Wars: Journey to Star Wars: The Last Jedi – Captain Phasma along with the rest of the comics, books, etc.

Keep in mind, the number of people who go see The Last Jedi far outnumber the people who got the Captain Phasma comic, and so the mandate for the movie is probably, “Tell a story that works based on the movies, and don’t worry about all the extra stuff.” That’s not to say that Johnson couldn’t tie in other material (and in fact, he even trolled some detractors online by pulling a bit of Jedi lore from him shelf), but his primary goal is to tell the best story, not to recognize Star Wars stories outside of the movies. And frustration at that lack of recognition isn’t some reverence over a grand, unifying story as much as anger at a lack of payoff.

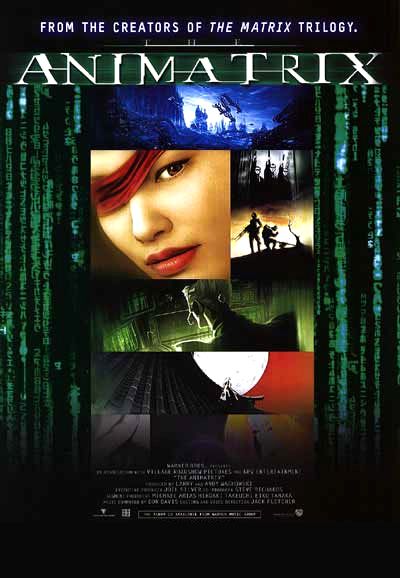

Payoff is certainly important, but in the web of ancillary stories, it’s almost impossible. We could get angry at a movie for not recognizing X, Y, and Z, but that anger seems more from the fact that when I read X, Y, and Z, I thought there would be more. I get this frustration. I remember when the Matrix sequels came out, and there was a big build up about how The Animatrix and the Enter the Matrix video game were incredibly important to the overall story. They weren’t, and while a couple of the animated shorts added a nice bit of background to The Matrix universe, they weren’t essential to the story, nor should they have been.

When you go to see a movie, no one hands you a stack of books, comics, video games, etc. By the same token, you typically don’t get a free copy of other stories from other mediums when you make a single purchase. This is by design, and in its best form, it’s just a way to provide a bit more color to the larger universe. The problem comes when fans demand that these stories become deeply interconnected despite the lack of a single author who could then somehow direct other authors to make sure that all of the stories appropriately recognize and respect each other. Keep in mind that such a position wouldn’t be in service of telling the best story, but in the sake of purchases supporting purchases.

The winners in this scenario aren’t fans and they’re certainly not storytellers. It’s the company that earns money from the IP. What you’re saying when you demand fidelity to ancillary material is that your purchase hasn’t been adequately recognized in spite of logistic and artistic concerns that would ultimately weaken the overall storytelling of both the main property and its spinoffs. Thus, your fandom isn’t tied to understanding a story or engaging with the material. Your fandom is tied to purchases, and a demand that one purchase recognize another purchase.

If that’s the field for fandom, you will inevitably feel ripped off because no company is going to do that. Few creators are going to be able to generate that amount of material across different mediums, and certainly wouldn’t be able to do it well. I understand that art can be collaborative, and that’s a good thing, but this is collaboration piled upon collaboration with no respect to how different mediums operate. An author has hundreds of pages to tell his or her story, and can use narrative devices that are unique to the medium. A director has about two hours to tell a story and has various restraints due to time and budget. Why should these two artists be held to the same standard of collaboration when they’re not even close to being on the same field? Yes, they’re both storytellers, but the similarities end there because the mediums are so different.

When fandom is tied to “I bought the most ancillary stuff, and therefore I should be rewarded with stories coming out the way I want,” the metrics have gone screwy. We’re no longer evaluating art but how well that art withstands the scrutiny of buying the most stuff. Under this model, being a fan is no longer about simply being passionate about a story or being inspired to tell your own stories. It’s about who buys the most stuff. A look, stuff isn’t bad. I like stuff! I’ve got the Buffy Season 8 comics and the Mondo Iron Giant. But my purchases haven’t made me more or less a fan than anyone else.

If you want to load up on ancillary stories, that’s fine. But using that ancillary material as a basis to build one’s fandom is a weak foundation.