In his exhilarating new film, Pina, German master Wim Wenders captures the brilliantly inventive dance world of late avant-garde choreographer Pina Bausch who led the Tanztheater Wuppertal ensemble. Wenders had conceived with Bausch a dance film like none seen before, one which would take the fullest advantage yet of new 3D technology to put the viewer deep inside Bausch’s playful, thrillingly unpredictable pieces. After her untimely death in 2009, Wenders continued with the project, turning it into the most exciting tribute he could imagine to the legendary artist. The end result is a sensual and visually stunning film.

Wenders talked to us at a roundtable interview about his collaboration with Bausch and her dancers, the technical challenges of the project, and its surprising emotional resonance. He told us what inspired him to make Pina, how 3D allowed him to take audiences into Bausch’s work and her imaginative sets and render the beauty and sheer physicality of the dances and dancers, and what he took away from the experience as a fellow artist and filmmaker. He also discussed the dance company’s plans to honor Bausch’s legacy through their performance at the London 2012 Olympics and why he thinks there’s nothing more exciting than to explore the human imagination and learn about another person’s creativity and craft.

Collider: What inspired you to make this movie about Pina?

WIM WENDERS: My first encounter with Pina took place 25 years ago. Until then, I had not much interest in dance. It was very limited. I thought it did not concern me. It wasn’t really for me. And then, one night, I saw a double bill of Pina’s Café Mueller and Le Sacre du Printemps against my will. My girlfriend forced me and it changed my life. It really was a life changing experience. I cried through the entire night helplessly, not understanding what was happening to me. Something big was happening and my body understood it and my brain lagged far behind, but it eventually caught up and then I knew. Pina and I got to know each other. I told her we have to make a film together. This is really extraordinary and I think between the two of us we can do something. Pina was skeptical but eventually she picked up on the idea, and then she started to push me and said “Wim, let’s do it. Let’s not just keep talking about it.” That’s when I got into trouble because then I had to come up with the goods and find out how to do it. That’s when I got into deep trouble, because with each piece I saw of Pina’s, and I saw all her pieces, every year I saw the new one, and each time I realized I couldn’t film it. My craft wasn’t good enough. I didn’t have the goods to really do justice to her work. It took us 20 years. Pina was very patient with me but she got a little desperate, “Wim, when are you ready?” I would have done it at any given moment. I would have dropped everything I did in between if I had known how to do it, but it had to be done. I knew the film that Pina and I wanted to do had to be done and it was really urgent. But there was no use in doing it if I didn’t feel confident that I was up to it.

What changed and made you realize you were ready to do it?

WENDERS: It changed one day on a day I did not expect anything would happen except some fun. It was a sunny day in May 2007 in Cannes. U2 played on the steps of the Festival Palais. It was nice. There was a huge crowd and afterwards we were all invited in to see a concert film, U2 in 3D. I put on the glasses for the first time. I didn’t expect anything but seeing a concert film with a gimmick. From the first moment on, I almost didn’t see the film. I just saw the possibility. I saw the answer to 20 years of hesitation and 20 years of not knowing what to do. I saw the answer was there. There was a tool that allowed me to be with Pina’s dancers and to be in the water swimming with the fish and not just looking from outside at the aquarium.

Is it better than a live performance because you’re in the middle of it?

WENDERS: You are in a privileged position, yes, but that you could do before. You could go with a regular camera into the middle of the stage, but you still wouldn’t feel that you could touch the dancers and that you were really there. The physicality of Pina’s dance was not approachable before there was 3D, before there was not only space and depth but also volume to the body.

Why was 3D the best way to film Pina’s dance style?

WENDERS: It is partly a question of dance in general. When I was hesitating and didn’t know how to film Pina’s dance, I looked at all sorts of dance films from the history of cinema and I felt there was a problem between film and dance. Even [with] these gorgeous films like Singing in the Rain and The Red Shoes, dancing in itself was always looking away from its possibilities. Even if Gene Kelly invented amazing things with the two dimensional possibilities to conquer space, it always ended up on a two-dimensional screen and something was wrong between film and dance to begin with. But, with Pina, especially because her dances are so physical and it involves the bodies of her dancers so much, it is also something between the audience and myself as a spectator. When I’m sitting, watching Pina’s work, I feel it in my own body. My body understands it and goes with it and my brain lags behind some and eventually follows. I felt that the physicality of the experience was lost on a two dimensional flat image. I was sure I couldn’t translate it. I was sure Pina would be disappointed. I needed something and I only understood what it was when I saw my first 3D film. It’s to be in the water with the dancers and not watching the aquarium from the outside looking in. For Pina’s work it was even more essential because it’s not just an aesthetic experience, it is an existential experience. It is about life. Pina maybe said it best herself when she defined very early on what she did. She said “I’m not interested in how my dancers move. I’m interested in what moves them,” and that is a huge difference. That’s a planet of difference. That’s a whole reversal of what dance was until then.

What went into choosing the four pieces you used in the film?

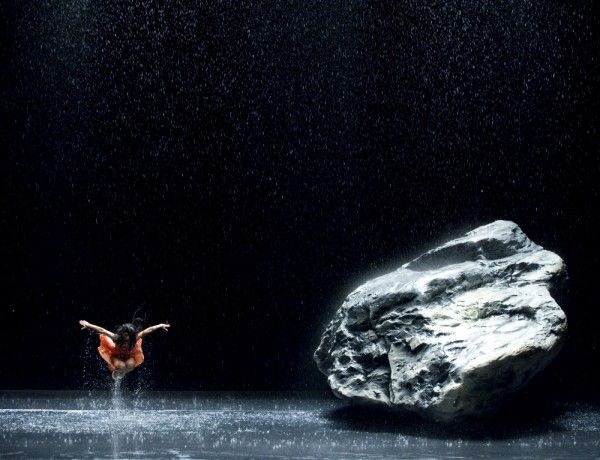

WENDERS: When I told Pina now I know how to do it and I came to see her, the first thing she wanted to decide was which pieces we were going to film. We started to actually prepare this film. We wrote a concept for the film together. Pina’s first thing was we need to decide because the pieces that you want to film, that we want to film, they have to be on the agenda of the theater. We have to rehearse them. They’re going to have to be public performances. Otherwise, we can’t film them. Together we selected these four pieces. Café Mueller and Le Sacre du Printemps we didn’t even have to discuss. It was right away on the table. They were the two big classics of the company. That was for sure. Then, we wanted to select a more modern piece and we went for Vollmond because it was Pina’s most successful piece of the century and she loved it and the dancers loved it. It had this attraction that it had all the water on the stage, and that, of course, would be gorgeous for 3D. So there was also no discussion. Vollmond was also [chosen] immediately. And then, we had three out of four. It could only be four because four was the maximum for one season, and we couldn’t afford to shoot for longer than one season so we had to reduce it to four. The fourth was a long decision. It took Pina and I weeks because all of a sudden selecting the fourth piece meant leaving everything else out. We had different favorites for a while and we finally decided on Kontakthof which is now in the film because it’s the only piece in dance history that is performed by three generations [of dancers]. That was something that really interested me a lot. Pina was also intrigued by the idea that I would film it so that we could cut through these different generations. That’s why we finally selected Kontakthof. Then, once it was on the schedule of the dance theater for the 2009-2010 season, for fall-winter, we had a start date. Pina and I started to write a concept and actively prepared the film together.

How did Pina’s death affect your approach to the project?

WENDERS: We were so much involved together in preparing and writing and planning the film that the fact that from one day to another Pina was no longer there, completely unforeseen by her family, her friends, her dancers, of course, was the end of the film. I just pulled the plug. I couldn’t imagine continuing because Pina was essential to the film and she was the center of the film. The film that I had in mind was a film about Pina’s eyes at work and that was no longer possible. I cancelled it the day that we heard of Pina’s death. We called all the producers and financiers and partners and all the crew and said “No more movie. Basta. It’s over.” It took several weeks, actually two months, until I understood that there was another film that one could make, not the film with Pina, but there was a film for Pina, and that there was a certain necessity for it. It slowly dawned on me the fact that none of her dancers had been able to say goodbye to Pina, and me neither, and we were very close friends. None of us was able to express our gratitude towards Pina. It was just a big hole in all our lives. For the dancers, it pulled the carpet from under their feet. Some of them had worked with Pina for 30 years.

I realized making the film for Pina, no long with her but for her, would be an important thing for the living as well as the homage for the dead artist that Pina was. We jumpstarted the film because they had already started to rehearse these four pieces and it became obvious that maybe this was the last time they were going to be performed. Pina had so much hope that we would find this new language together to film her pieces that I realized it was a shame and the wrong decision not to do it. We jumpstarted the film without much of a concept, because just filming the four pieces was not going to be a movie, but we jumped into it just in order to film the pieces and then took a long break of several months until the spring and then continued shooting the rest of the film. By then, we knew how to continue. By then, we had found a way to adopt Pina’s own method of working and make that the method of the movie and her own method of working with this unique approach of asking her dancers questions, very personal questions, sometimes general questions, all about this subject of the new piece, all circling around the subject of the piece. Pina would work on these questions with the dancers and they were not allowed to answer with words but only with dance and Pina would look at the answers and say “Well, you can be more honest or you can be more personal.” Or, the next day, she would say “What you showed me yesterday was pretty much a cliché of the answer to my question but can you be more specific? Can you tell me what you really think about it?” So they worked on these questions, and for weeks defined these answers together, and that became a wealth of hours and hours, hundreds of hours of material out of which Pina formed her pieces.

We adopted that method and I started asking the dancers questions, like Pina in the rehearsal room, and they all gave me lots of answers about Pina, about how Pina had seen them, how they had seen Pina’s eyes on them, how Pina had seen something in them that they didn’t even know themselves, and each of them answered very personally with the only added rule of the game that, as I’m not a choreographer, I didn’t want to see anything improvised. They showed me things that they had worked on with Pina. They answered with something out of their long repertoire of scenes they had developed with Pina. A lot of them had never been in a piece but some of them had been in all the pieces. We developed this whole catalog of answers in the rehearsal room and then I started to envision how to film them. Because we didn’t have a stage or set at our disposal for these answers, I started to think of shooting these outdoors in the city of Wuppertal and I tried to find places for each and every one of these answers where the response of the dancing could be brought out in the best possible way.

Can you comment on Pina’s unique approach to dance? I believe she referred to it as dance theatre where sometimes her dancers spoke on stage?

WENDERS: Out of Pina’s unique method, sometimes they did develop scenes, choreographies, where language came into the game, but it was never really essential. It was more accidental. And, as is Pina’s method, her dancers were never performing parts. They were always themselves. They always had their own names on stage. They were never representing a character. They were always themselves. That’s a very different approach to dancing. From the beginning, they always had to be actors as well as dancers. They had to be great dancers, but they had to be able to perform scenes that normally dancers don’t do but only actors do. So they had to be actors and dancers at the same time which was quite unique. Of course, there are other companies that are working in the field of dance theatre now and it’s no longer as revolutionary as it was when Pina introduced it. It’s now an art form in itself. But it is the first time that dancers became actors and actors became dancers.

What were the challenges as well as the opportunities of working with 3D?

WENDERS: The challenge was huge because nobody knew much about it. We started shooting in 2009, way before Avatar came out, so I couldn’t call James Cameron on the phone if I’d had his number. Avatar was a rumor and most of the films that were out were animation. There wasn’t really any live action film. But I was convinced that 3D was the ideal language for dance. We would have not started the film without the arrival of 3D. It was the answer to twenty years of hesitation and stalling and ruining my brain over how to make an appropriate film of Pina’s work because I felt that my craft before could not do that. Finally, that was the language that we needed and there was this beautiful affinity between dance and 3D. I was sure that one could bring out the best in the other, but it was mainly wishful thinking because it wasn’t really there yet. When we started prepping and doing tests in 2008, 3D was in its infancy. Some of the problems we encountered in the very beginning were staggering. Depth was there and could represent space beautifully, but the first tests we did were a disaster because [of] movement. Anybody moving fast in front of the camera was impossible. My assistant, who made big arm movements, became a four-armed Indian goddess because there were four arms and he had multiple legs. The technology was not able to represent fast movement smoothly and elegantly. And, of course, if you shoot dance, it has to be elegant. Pina’s dance is so natural and so elegant we couldn’t possibly shoot it with a technology that made everything sort of jerky. So, we worked on that for a year and a half and it took us a long time to understand how to solve it. The challenge was big.

On the other hand, the opportunity was so fabulous because if you work with such a new language, and if you can invent it, that’s also a great privilege. I felt we just had to invent a different kind of 3D, and I saw the possibilities even if there was no film to back it up. I saw the possibility of inventing a 3D that you would see and forget after two minutes that you ever saw a movie differently, that would feel natural and would be physiologically correct, because as soon as you start getting involved with 3D, you understand the process. Basically, we’re trying to imitate what two eyes are doing and what our brain is doing with the information of two eyes, and that is what you try to achieve as good as possible with two cameras. Once you get into that, and once you start respecting what two eyes are doing all the time, to really be in awe of what eyes do anyway every day, then you have a different look at what two cameras do and you’re no longer tempted so much with all the effects that you can also do with 3D. The biggest danger in the course of making Pina was to fall for any of the obvious traps and they were there every day and we wanted to avoid them because we didn’t want the technology to be the hero of the film. We wanted Pina’s dance to be the attraction.

Can you talk about the extraordinary dance sequence you shot in 3D on the hanging monorail?

WENDERS: The monorail is a fantastic little thing that the city of Wuppertal built in 1900. It has existed now for 110 years. They built it the same year that Paris built the Eiffel Tower and they have a lot in common. There are the same structural elements. It was at a time when the little city of Wuppertal was quite rich because they had a lot of chemical industry. A lot of inventions were made there. Aspirin was invented in Wuppertal so the city could afford an extravagancy like the monorail and there’s nothing like it. The hanging train only exists in Wuppertal. For 3D, it’s a fantastic means of transportation. Nothing could be more ideal for gliding through the city like this thing in [the air]. It was fun to put one of the dancers into the hanging train with the performance of Godzilla. It wasn’t all that easy because the equipment was still quite heavy at the time. By now, all of it is much easier. We shot in the infancy of 3D but we managed. Definitely the most fun part of the entire shoot was shooting in the hanging train.

What made you decide to incorporate the model into the film?

WENDERS: The scene with the model was a little wishful thing of mine because I used that model to visualize some of the scenes. Storyboarding didn’t help much with 3D because you needed to understand where your camera had to be at any given moment in order to catch the architecture of Pina’s choreography in the best possible angle. I was working with a model and one day I thought it would be nice to incorporate the model into the film because 3D has one strange deficiency. If you shoot from higher above, a high angle looking down, you can do whatever you want, but people appear miniaturized and people appear like dwarves. If you look at only one camera, the phenomenon is not there, but if you look at it with your own glasses in three dimensions, it’s like looking into a puppet’s house. I thought maybe we could use the effect somewhere instead of just fighting it. That’s why I came up with the idea of the little model. My stereographer, Alain (Derobe), said it’s never going to work because we need motion control and we don’t have the means to do this. He was very skeptical, but we did it and then it worked out magically. Alain was thrilled because it was done very innocently. We didn’t have any budget for this. This was done strictly on spec and it worked.

Can you talk about the compelling silent portraits you filmed in 3D of each of the dancers?

WENDERS: The most successful 3D application for me in this film is none of the big crane shots. It’s none of the choreography shots. It’s none of the spectacular things that we certainly did. For me, the big revelation and the most effective shot, which was a shock to me, were these close-ups by the dancers. Their silent portraits when they’re just sitting there all by themselves in a little corner of the stage, [like] a little room. There was a wall and they sat in front of the camera and we were alone, the dancers and myself. The crew was gone. They turned on the camera and the lights and then everybody left. I was just alone with them. I said I wanted this to be like a session with a painter. You would just sit there and sometimes in between you would look at the painter like a friend. But mostly, I wanted them to feel alone and be in their own thoughts. That was the great revelation because I had my little 3D monitor in front of me and I was sitting behind the camera so they could not see me. They were totally alone just facing the lens of the camera and that was a real shock for me to realize that 3D did something that I hadn’t seen before, that I hadn’t seen in any of the big choreographies on the stage. I had seen there was depth and space but I had not seen that a body could have volume. The body was round and the face was a landscape and [there was] the presence of these actors. They were just sitting on a stool in front of the camera. I had goosebumps each time because that was the big thing that I didn’t even think 3D could do. It could represent the human body in a very different way. The presence of the person in front of the 3D camera is frightening almost, because he or she is so much there and that for me was the greatest thing of all. That also brought out their individuality and their identity. Pina’s work has always been a switch for everybody’s identity and there they were so much by themselves and on their own. I was able to introduce them to the audience in such a different way than ever before, in person, in front of the camera.

There was no notion at the beginning that there would be talking. We shot all these portraits silently and in the editing room for about a year there was no language. I intended to make a film without language because from the beginning of the project with Pina we had two ground rules. One was no biography. Pina didn’t want any biographical elements in the film which I totally accepted because she wanted it to be about her work. The second ground rule was no interviews. Pina hated to talk and hated to explain and interpret her work. When she was doing interviews, and she had to do a lot, it always felt like she was betraying her work and I agreed with her. I told her I’m not going to ask you a single question. I just want to observe you. When Pina passed away, I stuck to these two rules in the film we made without her. I didn’t do any interviews with the dancers, but in our preparation, when I discussed with each and every one of them how they would respond to my questions about Pina, and they showed me their answer, I had long conversations with each and every one about their own relation with Pina. When had they started together? How old were they? How had they experienced Pina’s method for the first time? And, how had they grown into the company? But I did these conversations in order to be better able to shoot their responses. I never thought we would use any of this.

In the editing room, when we were almost finished with the film, I felt somehow it was a little too cryptic and people who didn’t know anything about Pina would want to know a little bit more about the relation of the dancers with Pina and about how the work happened. But I didn’t want to add a narration to the film, let alone my own voice. That was out of the question. Then I remembered our conversations and I went back to listen to all of them. I picked a few lines for each of them and I played them their own conversations and we transcribed them and together we chose for each and every one a couple of their own lines. We re-recorded them and they’re now in the film, not as interviews but more like interior monologues, like you could listen to their thoughts. They’re not interviews because I didn’t want to have talking heads in this film. I felt Pina would not have liked that and would not have approved of that message. What the dancers now say is in no way explanatory. It fills in on their relationship and it certainly doesn’t interpret the work.

You’ve done several documentaries about artists. How do you see your own role as an artist portraying other artists’ work?

WENDERS: First of all, there’s curiosity because sometimes I really think the last adventure left on this planet is creativity because we’ve been everywhere. There’s not much left to explore. But there’s a lot of exploration left in the human imagination, and I think there’s nothing more exciting than to learn about somebody’s creativity and also their craft and you have no idea. I made a film about a fashion designer (Yohji Yamamoto in Notebook on Cities and Clothes). I discovered the world of these old and forgotten musicians in Havana (Buena Vista Social Club). Pina’s world was such a parallel universe to everything I knew and it had so much to do also with my own craft. You see, filmmakers, we’re all sort of a little cocky because we think we know a lot about body language. By the nature of our profession, we have actors in front of cameras and we correct what they do. We tell them to move differently. We tell them to adjust their body language, and the famous presence of the actor is his or her body language. That is what makes them special and a movie star. An actor’s capital is his body. So, as film directors, we think we’re experts by default. And then, you get to know the work of Pina Bausch and you realize there is a real expert, and she deciphers this language in ways that we have never even started to understand. She is able to see layers and layers of this body language that none of us has ever understood. It’s a great lesson in modesty that you realize you’re illiterate in a field that you think you’re an expert in. For me, that was a great lesson that I learned from Pina, and that’s one of the reasons I wanted to make this film because I saw that she knew so much more than I or we did.

What do you hope Pina would think of the film?

WENDERS: I had to face that question every day. We had prepared the film so long together, and then all of a sudden I was there making it alone and I was shooting her pieces. Pina was not at my side. We couldn’t discuss the set-ups. I had to decide on my own, and so she was looking over my shoulder with each and every shot, and I had to answer that question to myself. Does Pina like it? Is this what I promised you? Is this good enough? I had to answer the question each and every day and, of course, with a finished film. It’s hard to say how you get the answer because Pina was very, very present in the film for all of us – for the dancers even more than for me. It felt all the time that her spirit was with us in an amazing way. When I finally edited the film, of course, I first showed it to the dancers. I had shown it to the artistic directors a lot of times in the course of the editing. They had always seen it and had advised me a lot on the dance questions, when I had several takes, and when I needed to know which take was dance-wise better than the others. They helped me a lot. But then, I showed the finished film to the dancers. [It was] only when they really appreciated it and when they felt that Pina’s universe was well and preserved in a film that I then felt Pina would have approved of it.

What will happen now to the Tanztheater Wuppertal ensemble, the dance troupe that Pina started 30 years ago?

WENDERS: The day that the dancers heard of Pina’s death, they were on tour in Poland in Krakow. They decided to go on stage and dance even if they were in tears because they realized that Pina would have wanted them to dance. Pina’s motto was “Dance, otherwise we are lost.” She really meant it, that dance was her answer to life and to the troubles and to the problems that can arise. That was her way to deal with everything, to dance. The dancers realized they had to dance and so they danced. In the following weeks, they decided to stay together as a company. They selected an artistic direction among themselves. Pina’s oldest dancer, who is also in the film in the first hour, and her longtime assistant, they became the artistic directors, and together they decided to fulfill all the obligations that the company and Pina had undergone for the next three years. So they continued, but they were still in a state of shock. I mean, they wanted to continue but they really lacked a lot of the confidence, because with Pina gone, for a lot of them, it was very much a question of how they could continue without Pina’s look on them. The film really helped in finding and repositioning their own attitude and their own confidence in representing her work.

Of course, there’s a body of 40 pieces, a body of work that Pina left, and they are the only ones that can represent these pieces. Since Pina’s death in summer 2009, they continued to stage and rehearse and do some of the older pieces. Pina, in her lifetime, always had an assistant or two from among the dancers who was responsible for one piece, so each of the pieces had dancers attached to them. They now continue to do a lot of the pieces that some of the young dancers had never done before and had not done with Pina. They represent this body of work now with a lot of confidence and they’re actually now doing something that nobody thought was possible. Pina had signed a contract a year before her death to appear with her company during the Olympic Games in London and do ten pieces in two theaters in London. After her death, it seemed out of the question. The company is now doing this. They’re doing a marathon of ten pieces in London, the biggest thing the company has ever done in their 40 years of existence, and they’re doing it with a lot of pride and confidence. I am very sure it will be fantastic. After that, at the moment, it’s open because they obliged themselves for three years and what’s going to happen afterwards, we will see.

Pina opens in New York on December 23, 2011 and in Los Angeles on January 13, 2012.