Find some glow sticks and do your best to evade law enforcement because music festival season has begun! If there’s anything America loves more than actual music festivals, it’s documentaries about music festivals. From the legendary (Monterey Pop) to the disastrous (Fyre), these special films often serve as time capsules that preserve both the good and bad of an era’s youth culture. But one festival doc reigns supreme and always will: Woodstock. Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 masterpiece captured a historic event that is unlikely to be repeated, inspired future generations of festival planners and goers, had unprecedented free-rein access that will likely never be granted again, helped launch the careers of Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker, popularized the innovative split-screen technique, and even inspired an iconic Apple iPod ad. By revisiting this unforgettable film, we’ll see the vast legacy it left on Hollywood and popular culture at large. There will never be another music festival doc quite like this one.

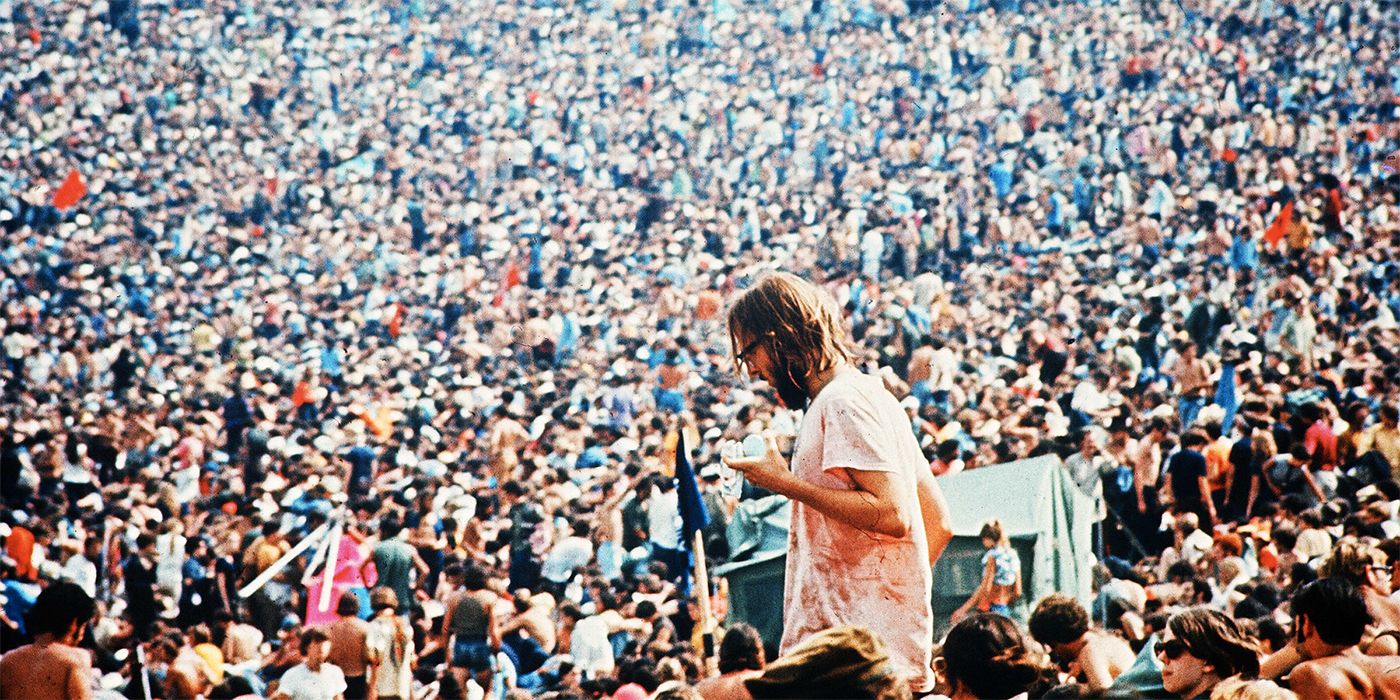

The 1969 Woodstock Music and Art Fair drew over 400,000 attendees to a sleepy dairy farm in upstate New York. Although some big names in the music world were scheduled to perform, nobody expected a turnout quite like that. To paraphrase Arlo Guthrie, the New York State Thruway was closed, man, if you can dig that. Director Michael Wadleigh was asked to film the event, and he brought with him the most talented New York filmmakers he could find, including Martin Scorsese, Thelma Schoonmaker, David Myers (cinematographer on George Lucas’ THX 1138), Jere Huggins (future assembly editor on Pulp Fiction), and Yeu-Bun Yee (also an editor on Scorsese’s The Last Waltz).

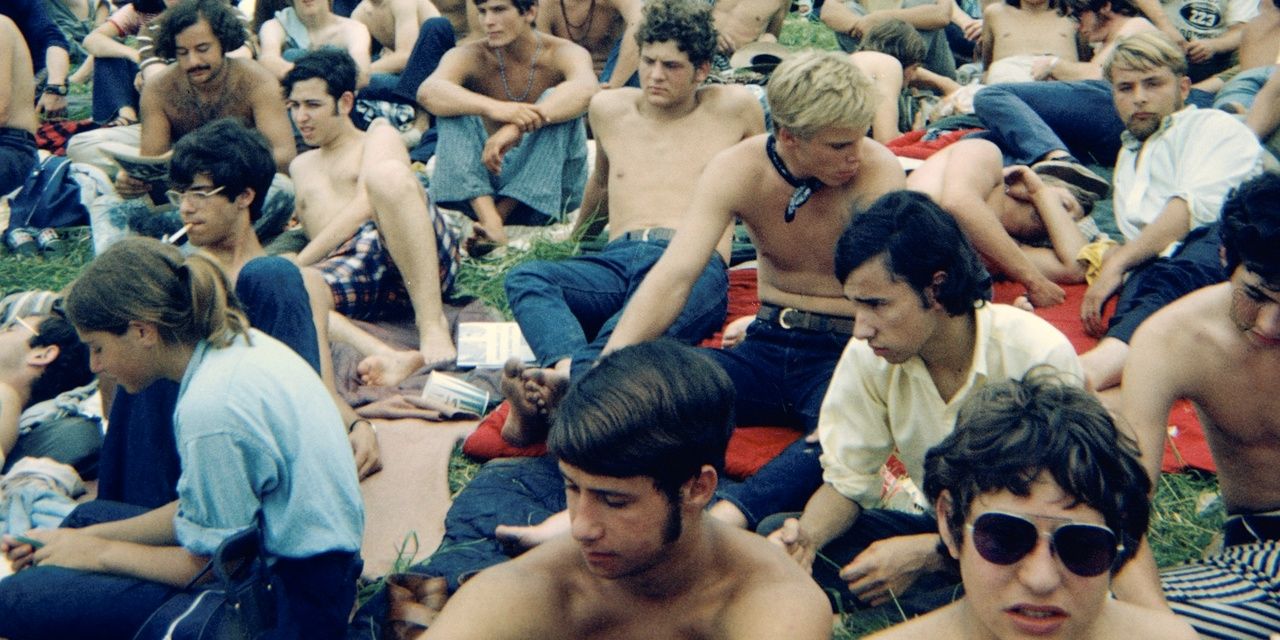

The festival organizers, who lost considerable amounts of money putting on the festival, didn’t pay much attention to the filmmakers, what with 400,000 people swarming into a small town. Plus it was the 1960s, and restricting access to filmmakers was just, like, not cool, man. So Wadleigh and company had more or less free rein to film whatever they saw, including two festivalgoers engaging in some intimate activity, lots of drug use, young hippies discussing free love and polyamory, an acid freak wearing a Che Guevara t-shirt, naked people dancing in the mud, and a whole lot of other things that any responsible modern-day festival would not want to be shown in movie theaters.

It might be hard to imagine a music festival without dozens of prominently-advertised corporate sponsors, but back then festival organizers saw what they were doing as more of a crusade than a business venture. Compare what you see in Woodstock, filmed over 50 years ago, with what you see in many of today’s forgettable music festival docs that essentially function as 80-minute advertisements. While most people assume there is drug use going on at festivals, no responsible organizer would permit such activity to be brazenly displayed in theaters across the country. The Woodstock documentary takes a contrary view: not showing drug use is just hiding the truth of what the scene is all about.

After capturing all these memorable scenes, it was up to the editorial team to piece together 120 hours of footage, filmed by more than a dozen cameras. One of the solutions? Split screens. They allowed the audience to see multiple events or camera angles simultaneously. Today, such a technique seems old hat, but back then it was far less common. Other films around that time period, such as The Thomas Crown Affair, had memorably used split screens but not to the same effect as Woodstock. Following the release of Woodstock, which was enormously popular and the fifth-highest grossing film of the year, split screens would be utilized to memorable effect in films such as The Andromeda Strain and Carrie.

Seeing multiple scenes playing out at once allowed the audience to virtually jump around the festival, keeping just as close an eye on the festival-goers as the performers. Although contemporary music festival docs may feature some attendees here and there, none make them the stars of the show like Woodstock. Indeed, part of what makes the film so special is that it is just as interested in the cultural phenomenon unfolding as it is in Jimi Hendrix’s guitar solos or Jerry Garcia passing around a joint. We are treated to many on-the-fly interviews in which hippies discuss their lives, their values, their families, and their politics. Wadleigh certainly understood he was capturing a special moment in time. It was a wildly different experience than celebs at Coachella posing with coconut water bottles for a branded Instagram post.

Among the editors working tirelessly to splice all of this footage together was the now legendary director/editor duo of Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker. For her work on Woodstock, Schoonmaker would receive her first Oscar nomination, and it’s easy to see why. Her dramatic use of freeze frames, such as when we see The Who’s Pete Townshend suspended in mid-air during a particularly energetic performance, are unforgettable. Her ability to sift through colossal amounts of footage to distill a historic event to its most essential moments is a remarkable feat. After editing Woodstock, Schoonmaker would again collaborate with Scorsese on 1980s Raging Bull and never look back, becoming the single most important creative partner in Scorsese’s career.

Among the many now-iconic images in Woodstock is one particularly memorable sequence that might seem familiar to people who remember the heyday of the Apple iPod. In one scene, we see a man dancing in that very peculiar but enchanting improvisational hippie style, as the sun begins to set behind him. As the sky grows darker, the man becomes a dancing silhouette against the deep-blue heavens. This moment would inspire a popular series of commercials for the iPod, released in 2003. To a cynic, perhaps this ad campaign symbolizes how the 60s counterculture became just another way to sell products, but it undeniably proves Woodstock’s enduring influence on pop culture and creativity.

Although many festivals today chase the high of Woodstock, it’s impossible for them to recreate what was not just a music festival, but a singular moment in time, a cultural phenomenon. Most festivals today are branded spectacles that primarily celebrate hedonism. One could argue this was also true of the original Woodstock, but Wadleigh’s film certainly doesn’t portray it that way. In fact, many festival documentaries have revolved around the shattered dream of the allegedly idyllic Woodstock. Take for example, Fyre, about the mind-bogglingly disastrous Fyre Festival, or more obviously, HBO’s Woodstock 99: Peace, Love, and Rage, about a 30-year follow-up to the original Woodstock that essentially turned into a full-scale riot.

Indeed, as that festival and documentary prove, the original Woodstock cannot be recreated. It happened organically, unplanned, and against all odds. It created an atmosphere of artistic freedom for budding young filmmakers. And perhaps best of all, it inspired a classic documentary that influenced pop culture for decades to come, thus solidifying its status as the very best music festival documentary ever made.